Abyss: an action roguelike game

Last May, I published my first game on itch.io. Abyss is an action roguelike that takes you into the depths as you battle monsters and foes! Who lurks deep beneath? Find out here:

Instructions

Use directional keys or WASD to move. Works best on Chrome and in your

desktop. You can also download executables for MacOS and Linux in the itch.io page. Note: loading may take a while.

I shared it to my friends and some game dev communities. They all complimented the gameplay, enjoyed the choice of music, and loved the art style. Their feedback made my entire year! It feels good to work on something, sharing it out in the open, and receiving good reactions from it.

It feels good to work on something, sharing it out in the open, and receiving good reactions from it.

In this blogpost, I’ll talk about five lessons I learned from making my first game. As it turns out, game development is a different beast! Even though I’ve been programming professionally for three years now, there are lessons I’ve still come to learn.

- Limit your scope

- Set a schedule and stick to it

- Play with your strengths

- Join a community of like-minded folks

- Don’t forget to have fun!

I highly recommend playing the game first before reading the rest of the post. I’ll talk about few design decisions that may be considered as spoiler even if it’s just a small game.

1. Limit your scope

As a famous saying goes: “your first ten games will suck, so get them out of the way fast.”1 For me, it stresses the importance of shipping, and the enemy of shipping is scope creep. I want to finish a game and move on to the next one.

Your first ten games will suck, so get them out of the way fast

I work well with deadlines, so I gave myself ten weekends with two weeks of buffer (approximately three months). I also want to keep it simple, yet rich in variety. Given that timeframe, I kept my expectations low: I won’t be making the next AAA hit, so my goal is to simply “make a game that I will be delighted to play.”

My goal: make a game that I myself will be delighted to play.

This led to my decision to create a roguelike.2 Looking back, I benefited from this choice because:

- I can piggyback on procedural generation: I get a lot of variety for free.

- It’s tile-based: no need to write physics, just simple four-directional motion.

- It’s almost infinitely replayable: because of permadeath, I can focus on the core gameplay.

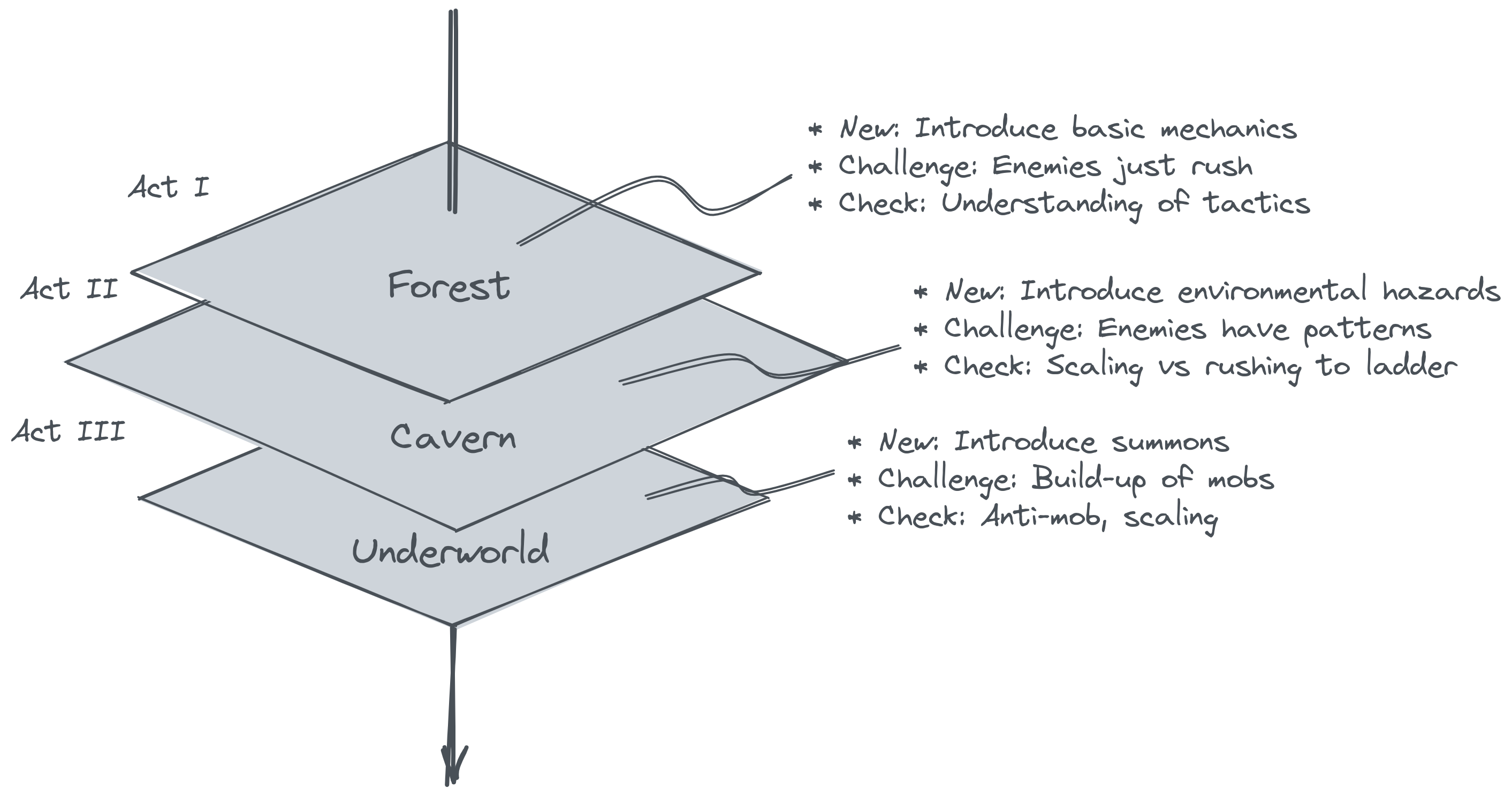

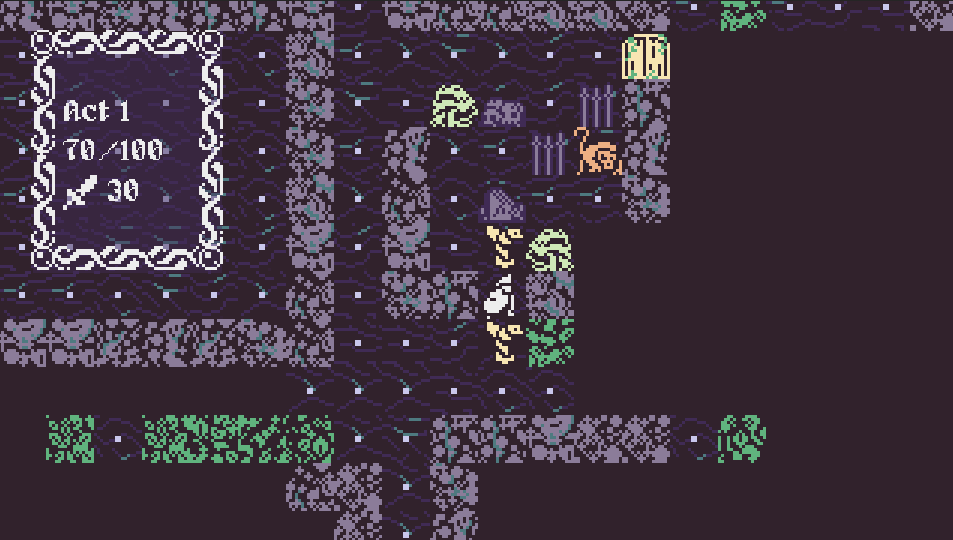

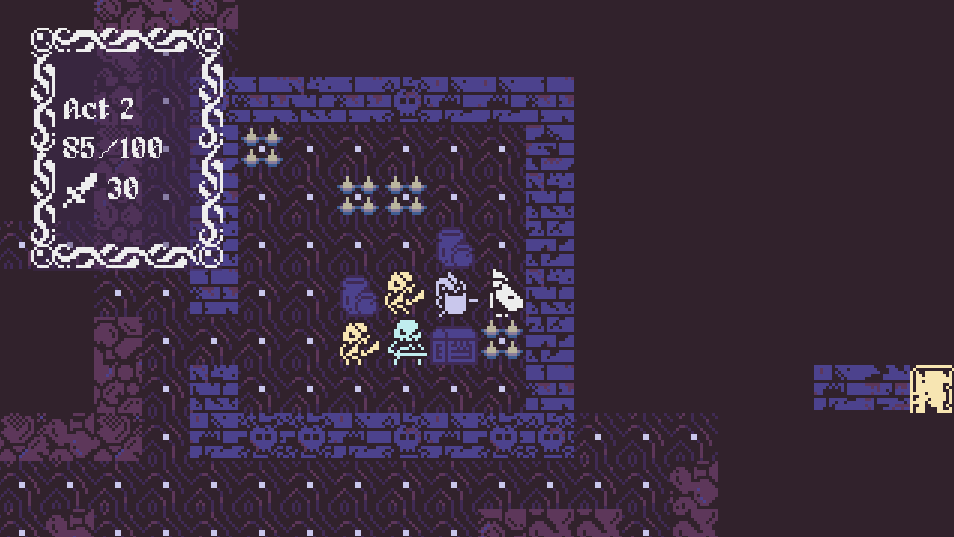

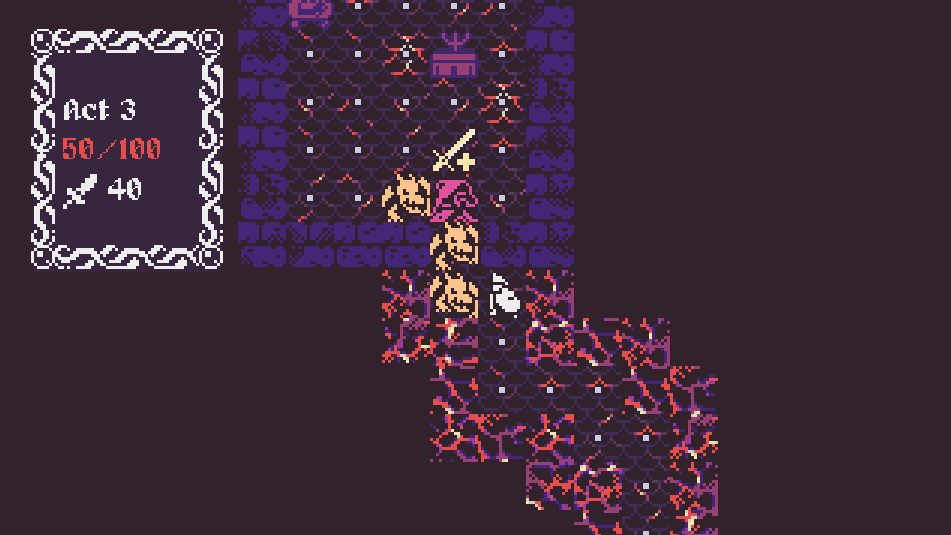

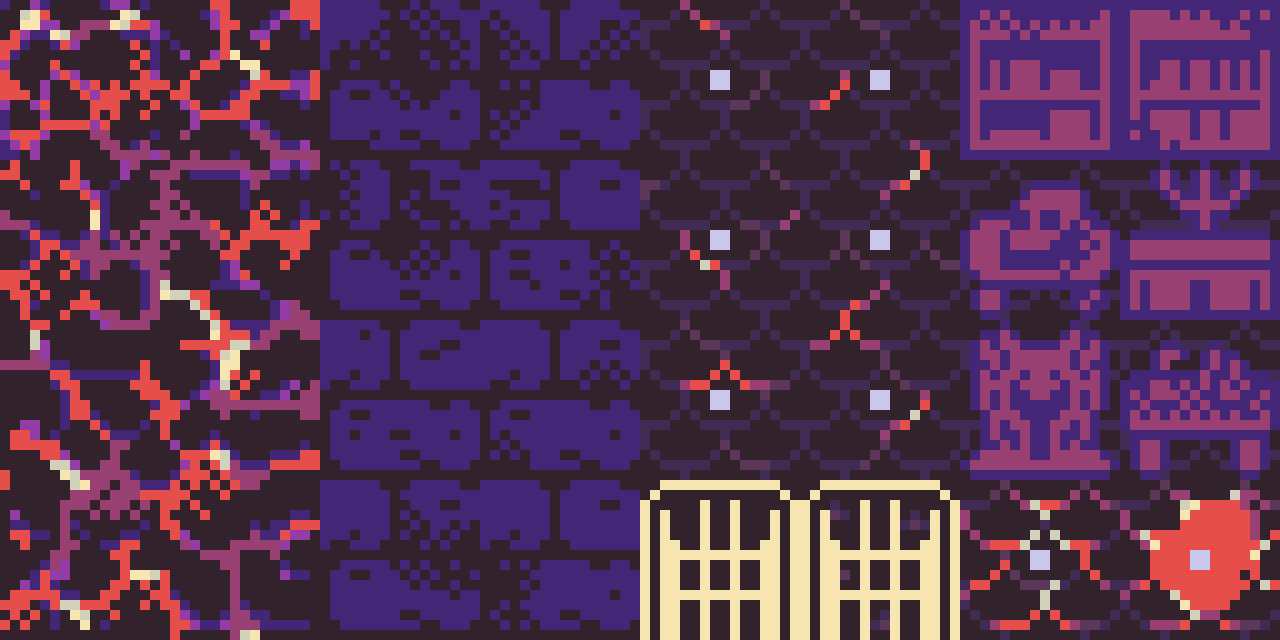

Figure: Three-act structure for my roguelike

In addition, I chose roguelikes because I’ve been playing that genre for the past few months. Hades, Dead Cells, and Slay the Spire became my inspiration. As for content, I restricted myself into three acts and one final boss. It’s good enough to keep the scope tiny and content rich, while establishing an end state.

With the scope set, it’s time to build!

2. Set a schedule and stick to it

My game won’t create itself, so I spent the weekends writing code and making art. Keeping a schedule forced me to be consistent, which in turn allowed short feedback loops. It also built momentum to finish the game.

One practice I found useful is participating in #screenshotsaturdays, i.e., to post a screenshot of my progress on Twitter every weekend. It’s good for pacing: thinking about what I want to share at the end of the day helps me start with the end in mind.

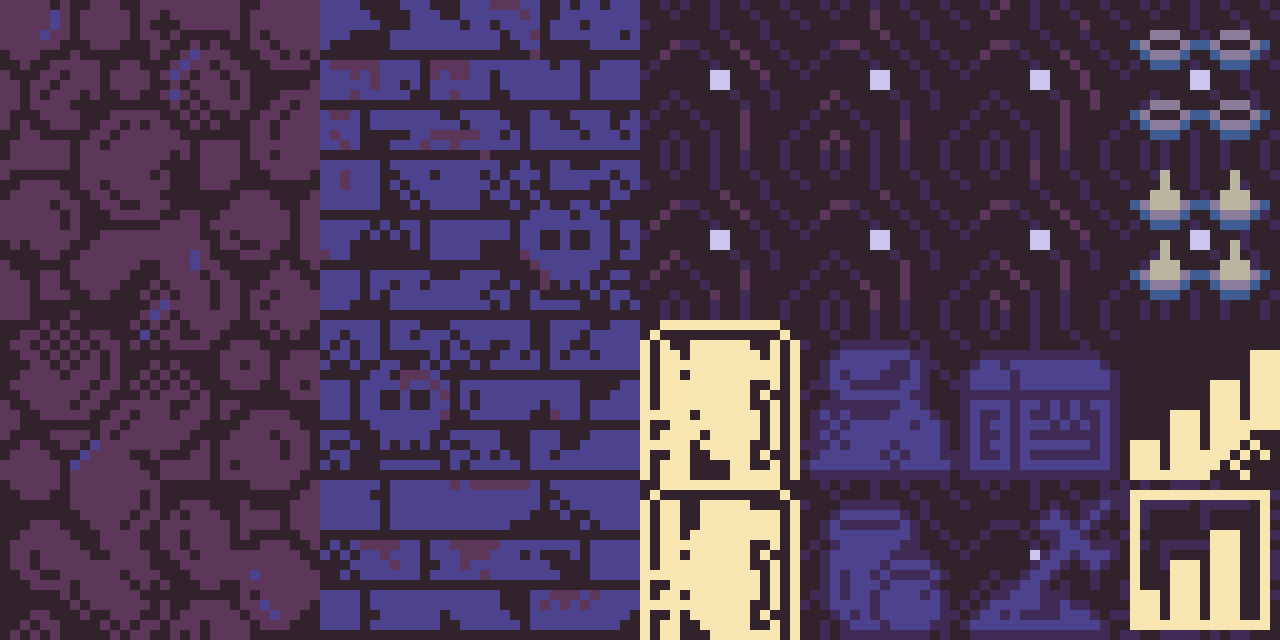

Figure: My #screenshotsaturday progress

Sharing on social media also encouraged me to build with the garage door open. At first it’s scary because I’m dipping my toes in new waters. But as time went by, I gained confidence as I get to gauge people’s reaction to my posts. You can check the full Twitter thread that I used.

My tweets also acted like a dev log. Looking back, they now serve as a reminder of how far I’ve come. It just started with simple raycasting, then some enemies, and now I have a full game! It feels good to be reminded that you’re improving, little by little— and it wouldn’t be possible without a consistent schedule.

3. Play with your strengths

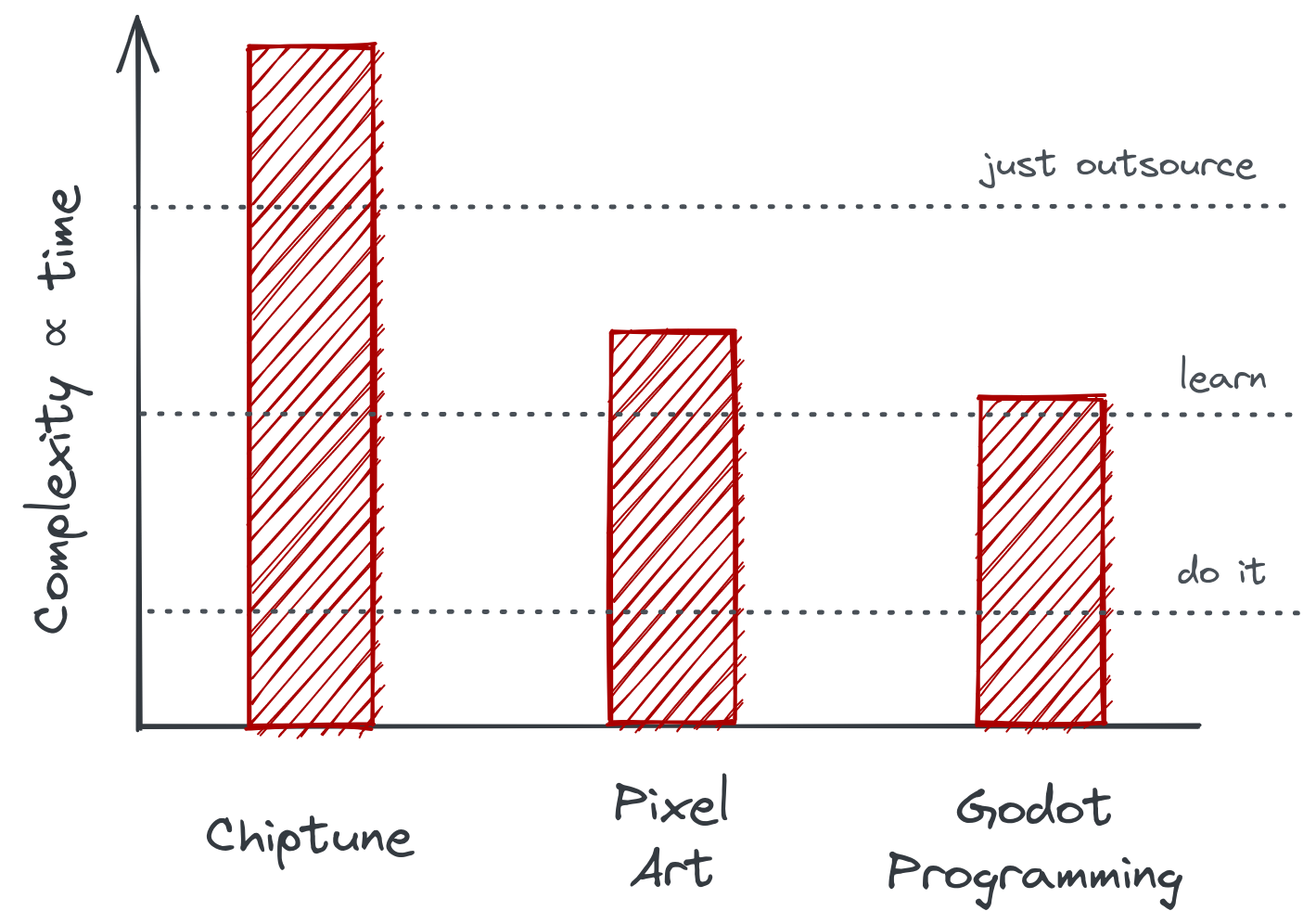

Unlike traditional software development, making a game involves a variety of seemingly disparate skills. It’s not only about programming, but also art and gameplay—a bit overwhelming if you ask me! However, if I want to finish my game within three months (see #1), I need to play with my strengths.

Before starting, I made a mental inventory of my skills against those required for game development. Then, I assessed which ones I’m (1) confident doing, (2) willing to learn, and (3) to just outsource. Here’s what it looks like:

Programming

I decided to use Godot Engine because it’s free, resembles Python, and has batteries included:

- Free: Godot is open-source, and I can just download it for free from Steam.

- Resembles Python: I was able to be productive in Godot right away.

- Batteries included: no need to reimplement complex algorithms (e.g., RayCast2D).

Figure: With Godot, I can just use the builtin raycasting algorithm to simulate

fog of war.

At first, I tried using Pico-8. However, that means I need to write my own pathfinding and dungeon generation algorithms. I’d love to, but it’s not the point of this exercise. With Godot, I can just import a class and configure it to my needs.

Of course, I am not yet fluent in Godot. There are still some concepts that I try to wrap my head around and best practices that I need to learn. For example, Nodes and Scenes took me some time, signals pattern is quite new, and my project structure is not yet idiomatic.

In addition, there are cases when instead of solving things properly, I just hacked my way out of it. Long way to go, but I’m happy with what I have so far!

Art

For graphics, I opted to use pixel art. I’ve been learning for almost a year now, and I feel confident in my abilities especially at lower dimensions (8x8 to 32x32). I chose Comfort44s for the color palette, then went for a retro aesthetic.

I borrowed some ideas from Celeste when designing my environment. For example, the lava in the final level was based from “Chapter 8: Core” while the overall feel of the dungeon came from “Chapter 5: Mirror Temple.” You can see their influences in the tilesets below:

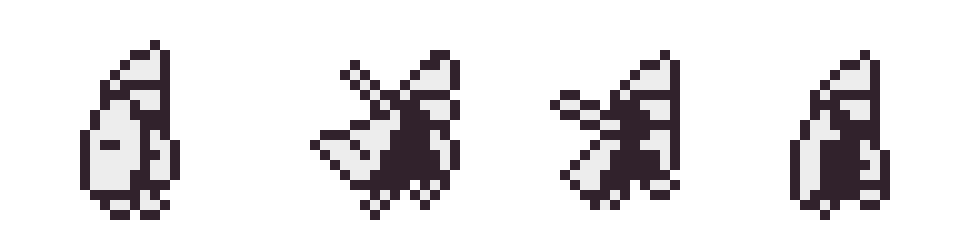

As for my sprite work, I’d like to think that I was able to convey the look and movement of my characters while ensuring that they stand out in the environment. I’m proud of it!

One of my favorites is the “slash animation” that I borrowed from Hollow Knight. Notice that you’ll only see the sword during the wind-down animation but the “crunchiness” of the slash is rendered by the slash effect and the in-game screen shake:

Music

To keep the retro style of the game, I decided to use chiptune for music. At first I thought of producing my own. I tried learning how to use Milkytracker and went through some of Gruber’s tutorials. However, it dawned on me that I’ll never be able to ship if I produce my own music, so instead I just outsourced from OpenGameArt.

The music and sound effects came from SubspaceAudio. Sure, I’ll probably learn how to make music in the future, but for now, using free assets will do. Thanks to Juhani Junkala for providing awesome tunes!

4. Join a community of like-minded folks

I can only go so far learning on my own. If I want to keep my momentum even after developing Abyss, then I need to join communities. I categorize them into three types: (1) passive, (2) tool-based, and (3) active.

Passive communities are those that I don’t actively participate in. A good example of this is Twitter. I created a List that only follows pixel artists, game developers, and publishers. This influenced my timeline into showing tweets related to what I want. Here, I just passively consume information.

Tool-based communities are Discord servers of my favorite tools. So far, I’ve joined the Aseprite, Godot Engine, and Bitsy Talk servers. With these communities, I was able to ask questions, discover tutorials, and connect with fellow hobbyists. I find it important to learn more about my tools, and improve how I use them.

Lastly, active communities are solely focused on game development itself. They usually host game jams, streams, and other activities on the topic. Two of my favorite ones are PIGSquad (Portland Indie Game Squad), and BuddyGameDev. The atmosphere is welcoming, and they cater to amateurs and professionals alike.

Surrounding myself with like-minded people helped me keep my momentum. I get to ask for feedback, share my work, and connect with others. They inspired me to finish the game, and to keep pursuing game development as a hobby!

5. Don’t forget to have fun!

Earlier, I mentioned that my goal is to create a game that I myself will be delighted to play. Since these are hobbies, fun and delight serve as strong signals. If I’m getting bored and burnt out because of it, then maybe it’s time to drop it off.

In the process of developing my first game, I started to realize that I’m making this for myself. Sure, I love sharing my work and would be excited if a lot of people play it—but if I myself don’t enjoy the process, then what is it for? This reminds me of a quote from my favorite Tom Scott video:

The world can be better because of what you built in the past. They don’t have to be big projects, they might just have an audience of one. And even if they don’t last, try to make sure they leave something positive behind…the code was never the important part.

That’s why I’m grateful for anyone who played and enjoyed my game. I see this as an expression of myself and it’s nice to see others partaking in it. I am happy to be accompanied by you in this game dev journey. With that I say:

Postscript

Last year, I realized that games are a good avenue for creative expression. I played a lot of them, sometimes more intentionally. You can see it in my analysis of Celeste, and in my end-of-year personal game awards. They’ve inspired me to try them out as a medium for creativity.

However, making games is quite an undertaking. There’s a lot to learn and it felt overwhelming. Given that, I’m reminded by this quote from another game dev:

“Small moves Ellie, small moves”

I’d like to think that I’m making small moves. It’s good to have people to look up to. As of now, these are: Daniel Linssen, Adamgryu, and Maddy Thorson for general game development, Mark Sparling3 and Lena Raine4 for composition, Johan Peitz and Noel Berry for programming, and Jen Zee for art.

It’s exciting to see what can be done at the highest levels of this craft, and I can’t wait to inch my way towards it! I’m still exploring different ways to do game development although I already have a lot of game ideas on my mind. I’ll still keep game development as a hobby, and I’m curious to see how far I can reach with little time and resources.

For people who played my first game, thank you! For those who were with me during the process, my deepest gratitude. On to the next one!

If you liked this, you might enjoy:

- What are Nodes and Scenes in Godot? A cooking perspective: here, I tried to explain a fundamental concept in Godot engine using a cooking analogy.

- Picollino: rought notes on movement: here you’ll see my initial attempts on Pico-8. I didn’t pursue this route because I find Godot easier.

- Scaling Celeste Mountain: Celeste is a game that has profoundly impacted me when I played it last year. It helped me understand my personal struggles, and opened my eyes to see games as a creative medium.

- My Game Awards 2020: a short tribute to all the games that I’ve played last year during the pandemic. Read this if you want to see my game recommendations.

Footnotes

-

I am not sure who is the original author of this quote. Nevertheless, I concur. Learning is about intentionally producing a large volume of work. ↩

-

According to the Berlin Interpretation, a roguelike has permadeath, turn-based, with elements of exploration and discovery. ↩

-

I really adored Mark Sparling’s composition in A Short Hike. Also, check out his Soundcloud! He used to make one chiptune everyday, intense! ↩

-

Lena Raine is a genius. Enough said. ↩