Labeling with GPT-3 using annotation guidelines

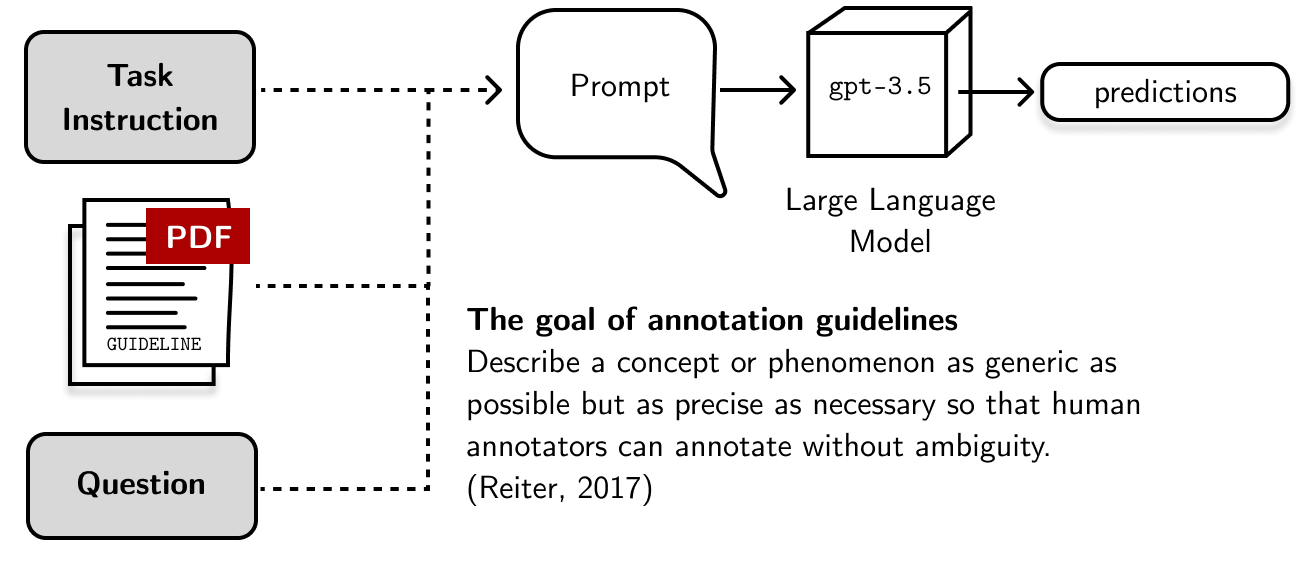

Previously, I investigated how we can incorporate large language models (LLMs) into our annotation workflows. It was a fun blog post, and I encourage you to read it. This time, I want to extend this idea by including annotation guidelines in the prompt. Because these guidelines were written to define the parameters of a task, we hope that they can improve the annotation process by providing more context and examples.

Because [annotation] guidelines were written to define the parameters of a task, we hope that they can improve the annotation process by providing more context and examples.

In this blog post, I want to focus on argumentative sentence detection: we want to know if a given text is an argument. I’ll use the “minimum wage” dataset from the UKP Sentential Argument Mining Corpus (Stab, et al., 2018). In addition, I’ll use three other annotation guidelines from different NLP papers. I based these choices from the work of Jakobsen et al. (2022).

Because each guideline defines an argument differently and asks for different

labels, I normalized them into 1: Argument and 0: No argument similar to

Jakobsen et al.’s (2022) work. The table below

summarizes these guidelines (the number beside each label is its normalized

version):

| Authors | Labels | How they defined an argument |

|---|---|---|

| Levy et al., 2018 | Accept (Pro/Con) (1), Reject (0) |

Here they defined a claim as the conclusion, that is, the assertion the argument aims to prove. They didn’t mention anything about premises. |

| Stab et al., 2018 | Attacking (1), opposing (1), non argument (0) |

They have an explicit requirement where each claim should be backed-up by another claim or premise. Claims alone don’t equate to an argument. |

| Shnarch et al., 2018 | Accept (1), Reject (0) |

They defined an argument as containing a claim (conclusion) and premise (evidence). Claims alone don’t equate to an argument. |

By incorporating both the annotation guideline and large language model, we can get LLM predictions by feeding annotation guidelines into the prompt. This is similar to my previous blog post with the addition of more context from the annotation guideline. The engineering challenge here is on feeding a long string of text into a prompt constrained to a set amount of tokens.

I plan to accomplish this task using Prodigy, an annotation tool, and LangChain, a library for working with large language models. You can find the source code from this Github repository.

To save costs, I’ll only be using the 496 samples from the test set. I also discarded the Morante et al, 2020 annotation guideline because it’s eight pages long and API calls can balloon from processing it.

Fitting annotation guidelines into the prompt

Fitting a long document into OpenAI’s prompt is one of the primary engineering

challenges in this project. The GPT-3.5 text-davinci-003 model only allows a

maximum request length of 4097 tokens, which are shared between the prompt and

its completion— most annotation guidelines won’t fit.

LangChain offers a simple solution:

split the document into chunks and think of prompts as functions. By doing so,

we can leverage a wide range of data engineering concepts such as map-reduce,

reranking, and sequential processing. The LangChain

API

dubs these as MapReduce, MapRerank, and Refine respectively.

LangChain offers a simple solution: split the document into chunks and think of prompts as functions. We can then leverage a wide range of data engineering concepts.

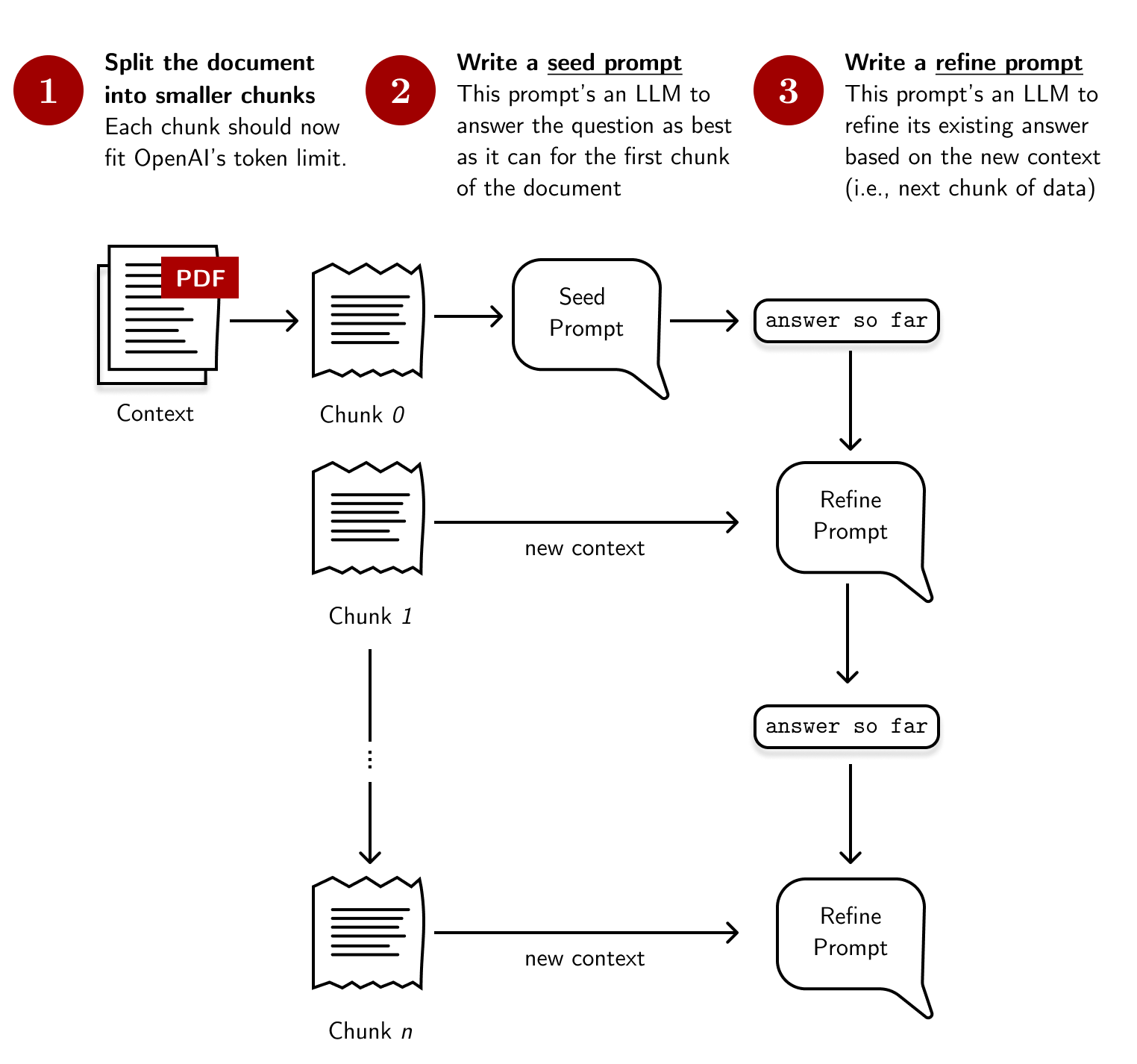

During my experiments, I found that using the sequential prompting technique,

Refine, works best for annotation guidelines. The output is more consistent

and the model does not fail at performing the task. The figure below provides an

overview of this process:

- Split the document into smaller chunks. I used LangChain’s built-in spaCy splitter that splits text into sentences. This process ensures that the text is still coherent when passed to the prompt, especially when an annotation guideline provides exemplars for the task.

-

Write a seed prompt. The seed prompt asks GPT-3.5 to classify an example given the first chunk of the annotation guideline. It then returns a preliminary answer that will be refined later on using the refine prompt. For our project, the seed prompt looks like this:

Context information is below. ----------------------------------------- {context} ----------------------------------------- Given the context information and not prior knowledge, classify the following text: {question} -

Write a refine prompt The refine prompt asks GPT-3.5 to refine their answer given new information. The prompt is called successively until all chunks are shown. Then, we take the refined answer and assign it as our LLM’s prediction. The refine prompt looks like this:

The original text to classify is as follows: {question} We have provided an existing answer: {existing_answer} We have the opportunity to refine the existing answer (only if needed) with some more context below. ---------------------------------------------- {context} ---------------------------------------------- Given the new context, refine the original answer to better classify the question. If the context isn't useful, return the original answer.

Notice that I’m using some terms from the Question-Answering domain: context refers to the chunk of text from the annotation guideline, and question is the example to be classified. I patterned my prompts to this domain because it’s easier to think of annotation as a question-answering task.

Funnily enough, this problem may be considered solved with the release of GPT-4. With a longer context length (32k tokens or roughly 25,000 words), you can fit in a whole annotation guideline without splitting it into chunks.

Comparing predictions to gold-standard data

For this evaluation step, I want to compare the predictions from each annotation

guideline to the gold-standard annotations found in the UKP dataset. First, I

normalized all labels into a binary classification task between an Argument

and No argument:

- Labels assigned to

Argument: Accept (Pro/Con), Attacking, Opposing, Accept - Labels assigned to

No argument: Reject, Non argument

This process gave us a dataset with \(227\) examples with the Argument class

and \(270\) examples with the No argument class. The F1-score for each

annotation guideline is shown below:

| Scores | Stab et al. (2018) | Levy et al. (2018) | Shnarch et al. (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro F1-score | \(\mathbf{68.35}\) | \(60.08\) | \(42.54\) |

| Macro F1-score | \(\mathbf{67.61}\) | \(53.71\) | \(37.94\) |

| F1-score (per type) | Stab et al. (2018) | Levy et al. (2018) | Shnarch et al. (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|

No argument (NoArgument) |

\(\mathbf{72.50}\) | \(89.26\) | \(54.83\) |

Argument (Argument) |

\(\mathbf{62.71}\) | \(36.54\) | \(21.05\) |

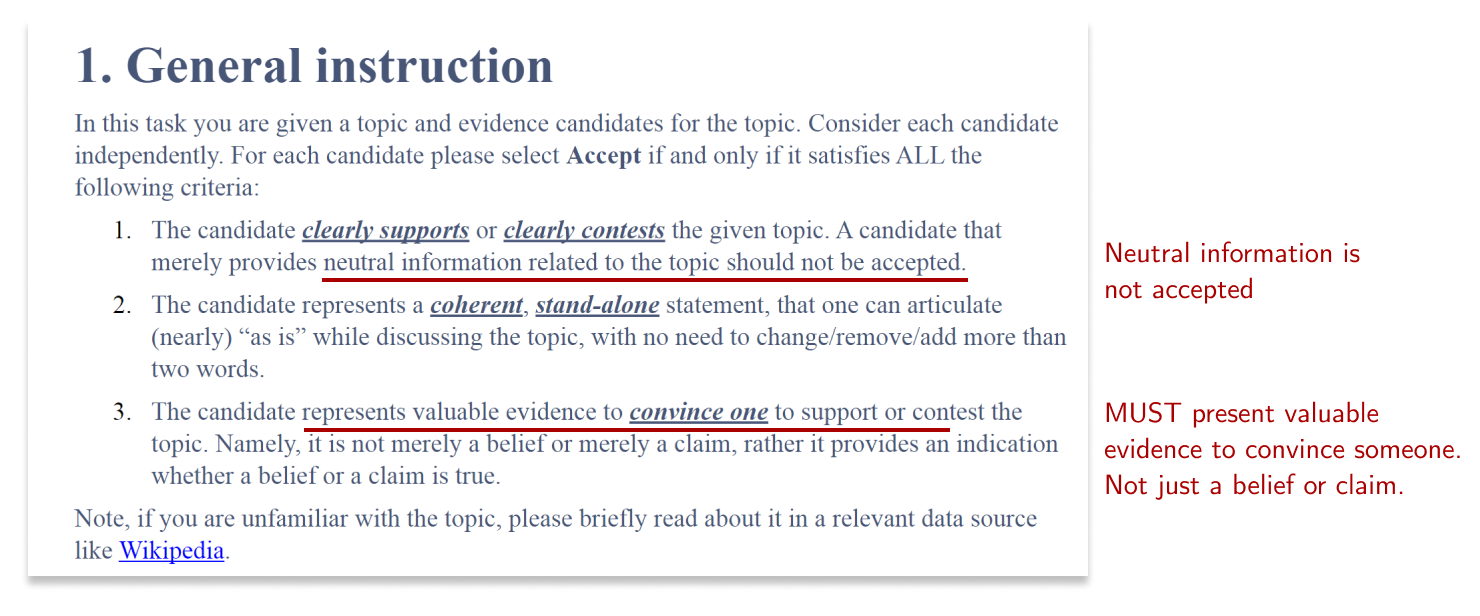

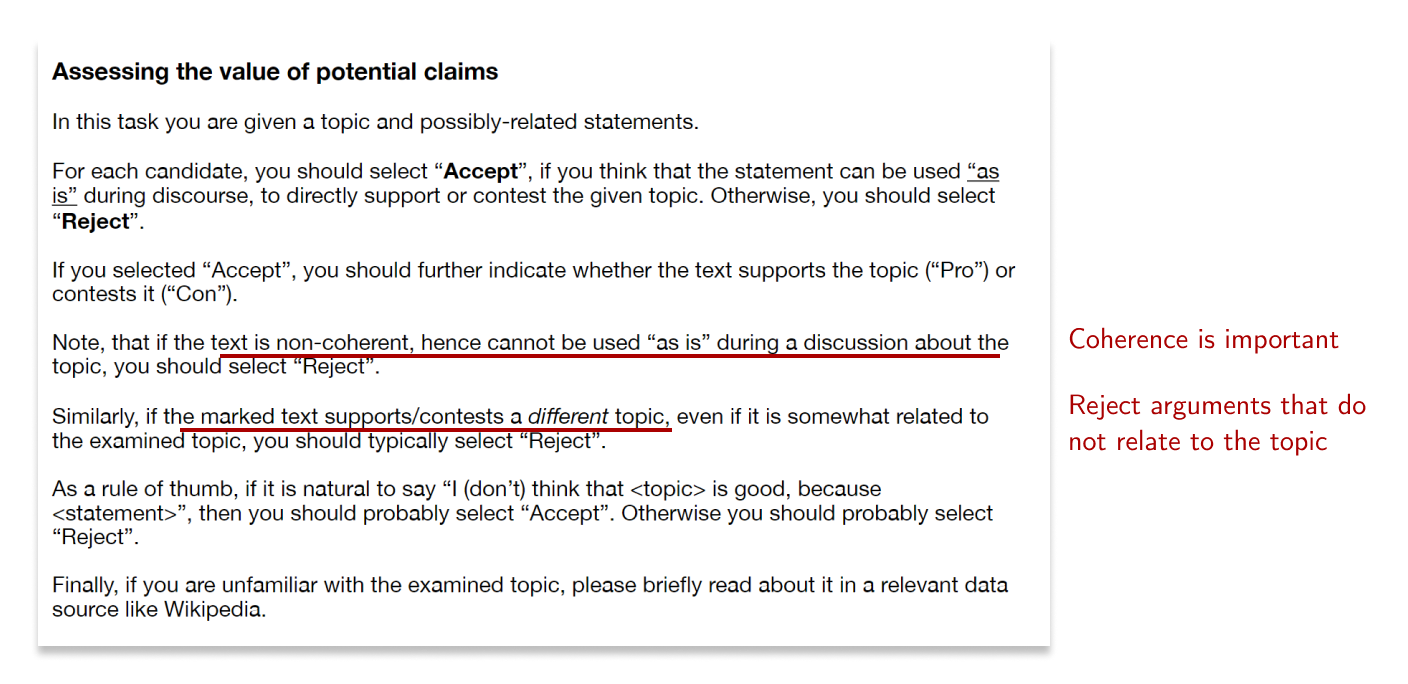

As expected, the performance of the Stab et al., (2018)

guideline is closest to the original annotations. It’s also interesting how the

results are heavily biased towards the NoArgument class for both Levy et al.

(2018) and Shnarch et al. (2018)

guidelines. From a qualitative inspection, these results make sense because the wording

from these guidelines denote a more stringent criteria for accepting statements as

arguments:

Figure: Portion of annotation guidelines from Shnarch et al. (2018)

Figure: Portion of annotation guidelines from Levy et al. (2018)

It’s still hard to say which exact statements from the guideline informed an

LLM’s decision. But because our prompting strategy refines the answer for each

chunk of text, it’s possible that original Accept answers were rejected

because of new information from the prompt.

Finally, I also noticed that the performance from the Stab et al. (2018) annotation guideline is worse than the supervised and zero-shot predictions from my previous blog post:

| Scores | Zero-shot | Supervised | Stab et al. (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro F1-score | \(\mathbf{81.45}\) | \(79.88\) | \(61.90\) |

| Macro F1-score | \(\mathbf{78.74}\) | \(77.52\) | \(55.02\) |

| F1-score (per type) | Zero-shot | Supervised | Stab, et al. (2018) |

|---|---|---|---|

Supporting argument (Argument_for) |

\(\mathbf{75.21}\) | \(73.60\) | \(48.74\) |

No argument (NoArgument) |

\(\mathbf{86.74}\) | \(85.66\) | \(72.50\) |

Opposing argument (Argument_against) |

\(\mathbf{74.26}\) | \(73.30\) | \(46.00\) |

It’s an interesting negative result because it ran contrary to what I expected: we already have the annotation guideline, isn’t it supposed to work well? However, I realized that it’s still difficult to make a straight-up comparison between two prompts: it’s possible that one prompt was written poorly (not “fine-tuned” given known prompt engineering techniques) than the other. Personally, I will still dabble into this research lead, but it’s also possible that writing a short and sweet zero-shot prompt works best for our task.

Cross-guideline evaluation

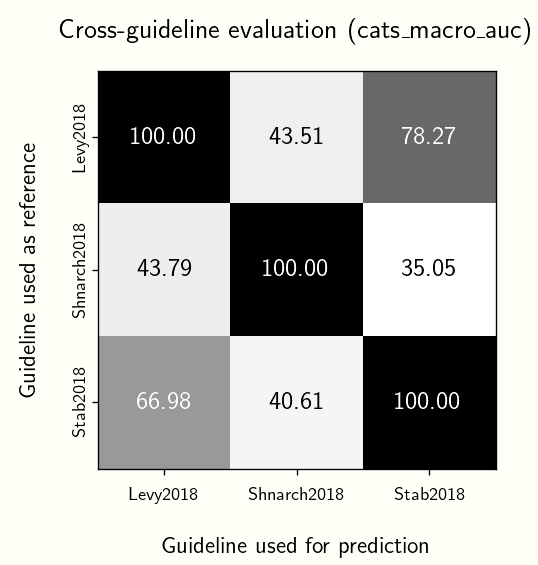

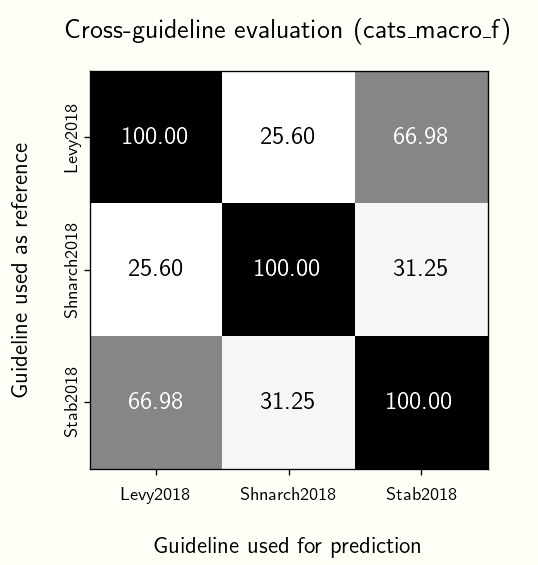

This time, let’s lean into the idea that LLM’s capture the intention of annotation guidelines and compare them against one another. We take one guideline as reference, the rest as predictions, and compute the F1-score. We then arrive at the graph below:

It’s interesting that for all cases, the Stab et al. (2018) annotation guideline performs best (of course, discounting cases when we evaluate a guideline to itself). On the other hand, the Shnarch et al. (2018) performs the worst.

I don’t think there’s anything vital to conclude from these results. Perhaps they say something about how strict a guideline is? Maybe this can lead to experiments that investigate how similar guidelines are to one another. We usually measure text similarity via some cosine distance between the text’s vectors. However, guidelines are intentional, and maybe something can be said about the products of these intentions, which in this case, are the annotations.

Final thoughts

In this blog post, we looked into how we can incorporate annotation guidelines into our annotation workflows by including them in the prompt. In order to get around OpenAI’s token limit, we partitioned our document and passed each chunk sequentially into the prompt. All of these were accomplished using Prodigy and LangChain.

When comparing to gold-standard annotations, the original guidelines for the UKP dataset performed better compared to others that were written for other tasks. However, a zero-shot approach outperformed all methods. In fact, a straightforward supervised approach outperforms a prompt with annotation guidelines. I see this more as a negative result.

Moving forward, I think much can still be done in this line of work. I imagine using this process to evaluate how well an annotation guideline “models” the task. I wouldn’t use it to get few-shot predictions, it’s costly and not performant. In addition, it might be interesting to incorporate annotation guidelines in the annotation UI, perhaps to highlight relevant parts of the document that’s useful to accomplish a task. I’m interested to hear any suggestions or thoughts about this experiment. Feel free to reach out or comment below!

References

- Eyal Shnarch, Leshem Choshen, Guy Moshkowich, Ranit Aharonov, and Noam Slonim. 2020. Unsupervised Expressive Rules Provide Explainability and Assist Human Experts Grasping New Domains. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pages 2678–2697, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Ran Levy, Ben Bogin, Shai Gretz, Ranit Aharonov, and Noam Slonim. 2018. Towards an argumentative content search engine using weak supervision. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 2066–2081, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Roser Morante, Chantal van Son, Isa Maks, and Piek Vossen. 2020. Annotating Perspectives on Vaccination. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, pages 4964–4973, Marseille, France. European Language Resources Association.

- Stab, C., Miller, T., Schiller, B., Rai, P., and Gurevych, I. (2018). Cross-topic argument mining from heterogeneous sources. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 3664–3674, Brussels, Belgium, October-November. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Thorn Jakobsen, T.S., Barrett, M., Søgaard, A., & Lassen, D.S. (2022). The Sensitivity of Annotator Bias to Task Definitions in Argument Mining. In Proceedings of the 16th Linguistic Annotation Workshop (LAW-XVI) within LREC2022, pp. 44-61, Marseille, France. European Language Resources Association.