Study notes on parameter-efficient finetuning techniques

Finetuning is a way to adapt pretrained language models (LMs) to a specific task or domain. It requires attaching a task head to the model and updating the weights of the entire network. However, this process can put a strain on one’s compute budget. This becomes more true as language models get larger and larger in every release.

In this blog post, I want to share my notes on parameter-efficient finetuning techniques (PEFT). Here, we only finetune a small number of parameters while keeping most of the LM parameters frozen. As a result, PEFT allows domain adaptation at a lower compute (and storage) cost. Lastly, this blog post is not a literature review; I will only discuss methods I personally like. For each PEFT, I will talk about its overview, related works, and high-level implementation.

Finetuning is the de facto transfer learning technique, but it has become inefficient

To recap, pretrained language models like BERT (Devlin et al., 2019) contain contextualized word representations that capture the meaning of each token and its context within the text. By themselves, they’re already useful. However, language models have enjoyed greater versatility and state-of-the-art performance because of finetuning (Howard and Ruder, 2018).

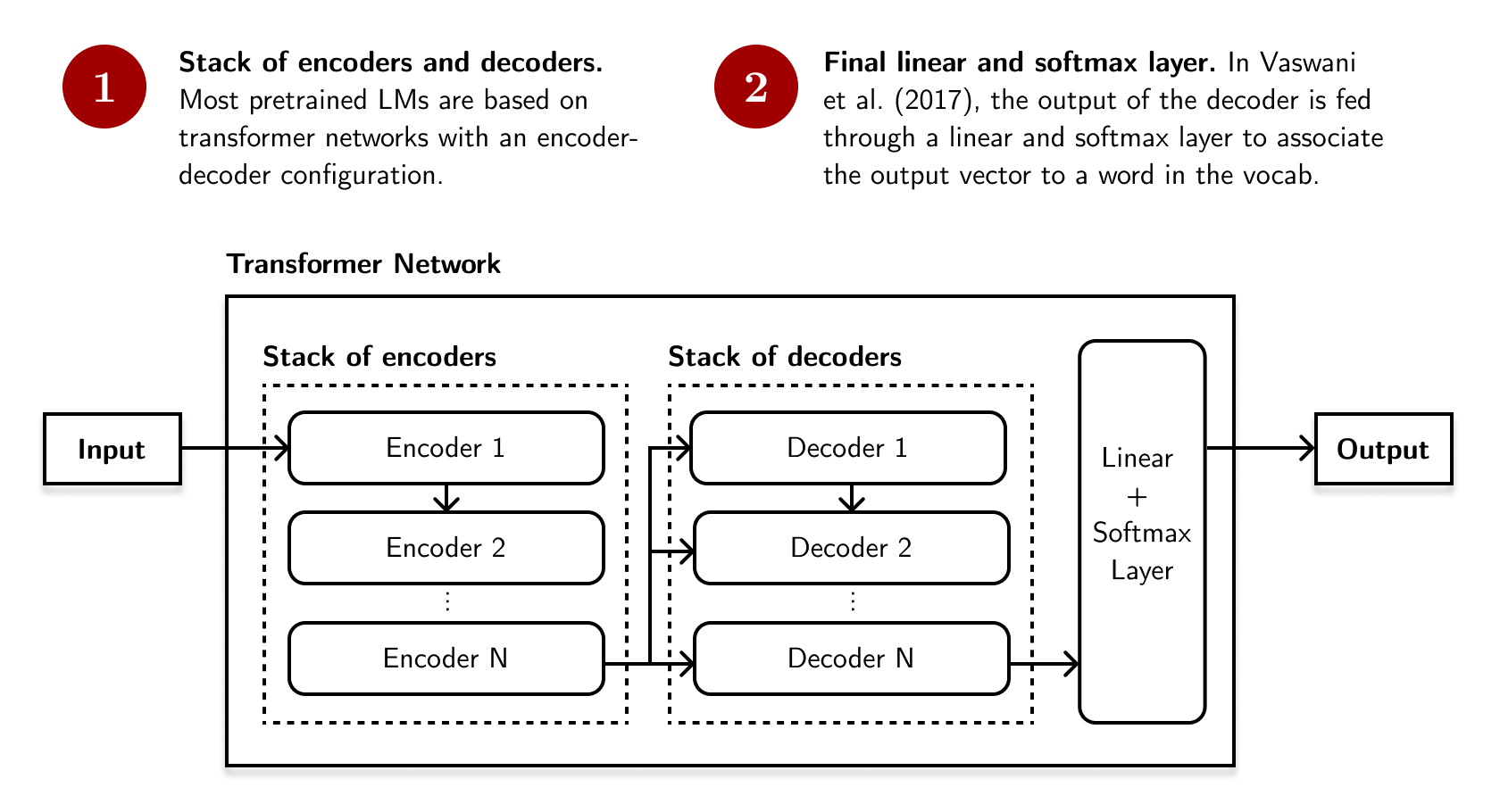

Much of the pretrained LMs we use today are based on transformer networks (Vaswani et al., 2017). Let’s review its architecture, as it will help us understand the PEFT techniques later on. Recall that most transformer networks consist of a stack of encoder and decoder layers with an attention mechanism:

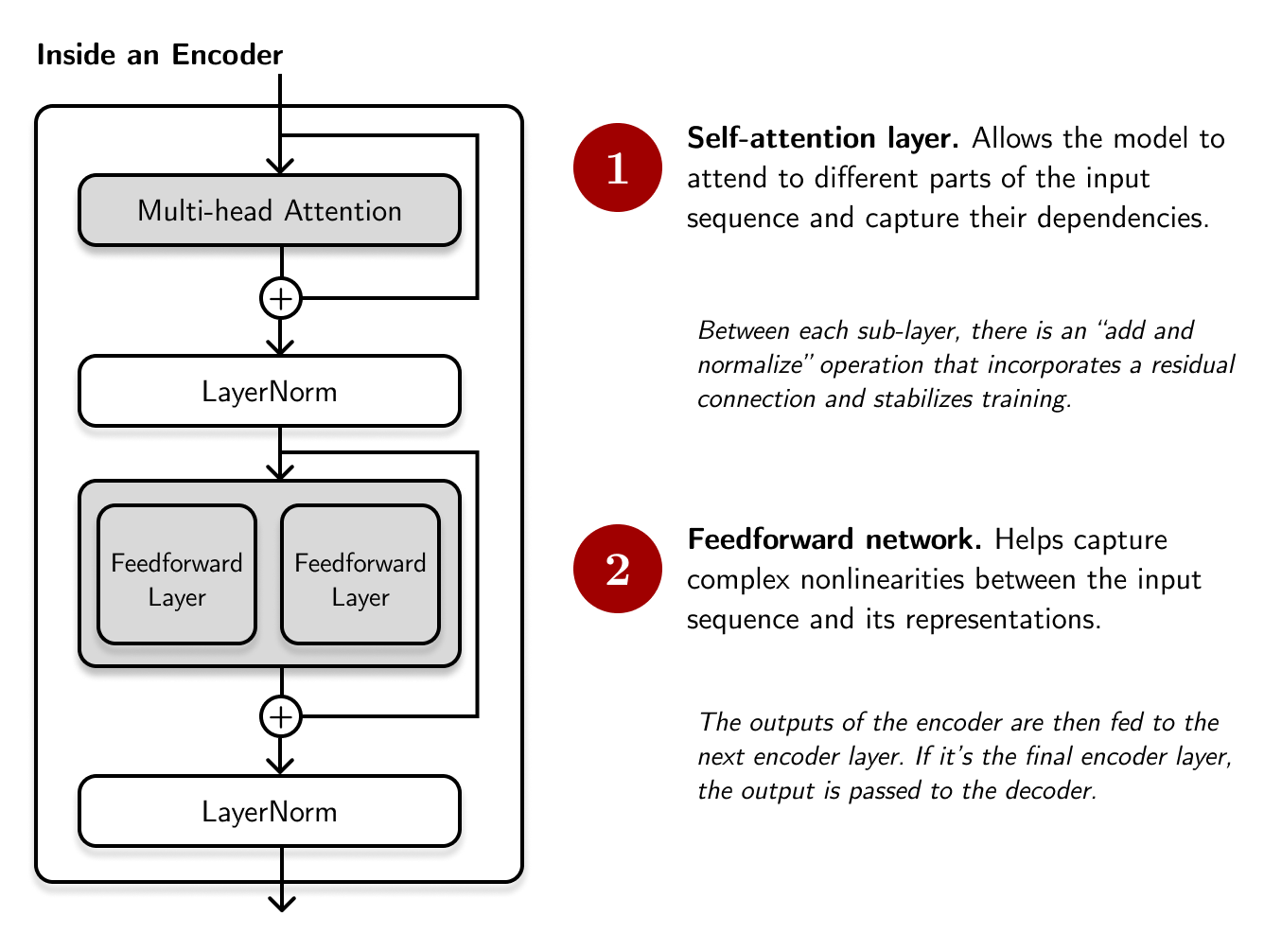

The encoder layer consists of two sub-layers: an attention layer and a feedforward network. Its outputs are passed to the decoder, consisting of the same two sub-layers plus a cross-attention mechanism that attends the encoder’s output. Between each sub-layer, there is a residual (or skip) connection that is normalized through LayerNorm (Ba et al., 2016).

For transformers like BERT, there is no generative step, hence it only contains encoders. Here’s what a typical encoder layer looks like:

# Pseudocode of a typical encoder layer

class Encoder:

def __call__(self, x: Tensor) -> Tensor:

residual = x

x = MultiHeadAttention(x)

x = LayerNorm(x + residual)

residual = x

x = FeedForwardLayers(x)

x = LayerNorm(x + residual)

return x

This encoder-only transformer uses multi-head attention, where the attention function is applied in parallel over \(N_h\) heads. So given (1) a sequence of \(m\) vectors \(\mathbf{C}\in \mathbb{R}^{m\times d}\) which we will perform attention to, and a (2) query vector \(\mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^{d}\), multi-head attention computes the output on each head and concatenates them:

\[MultiHeadAttention(\mathbf{C}, \mathbf{x}) = Concat(head_1, \dots, head_h)\\ where~~head_i = Attention(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{W}_q^{(i)}, \mathbf{C}\mathbf{W}_k^{(i)}, \mathbf{C}\mathbf{W}_v^{(i)})\]And the feedforward network consists of a two linear transformations with a ReLU activation function:

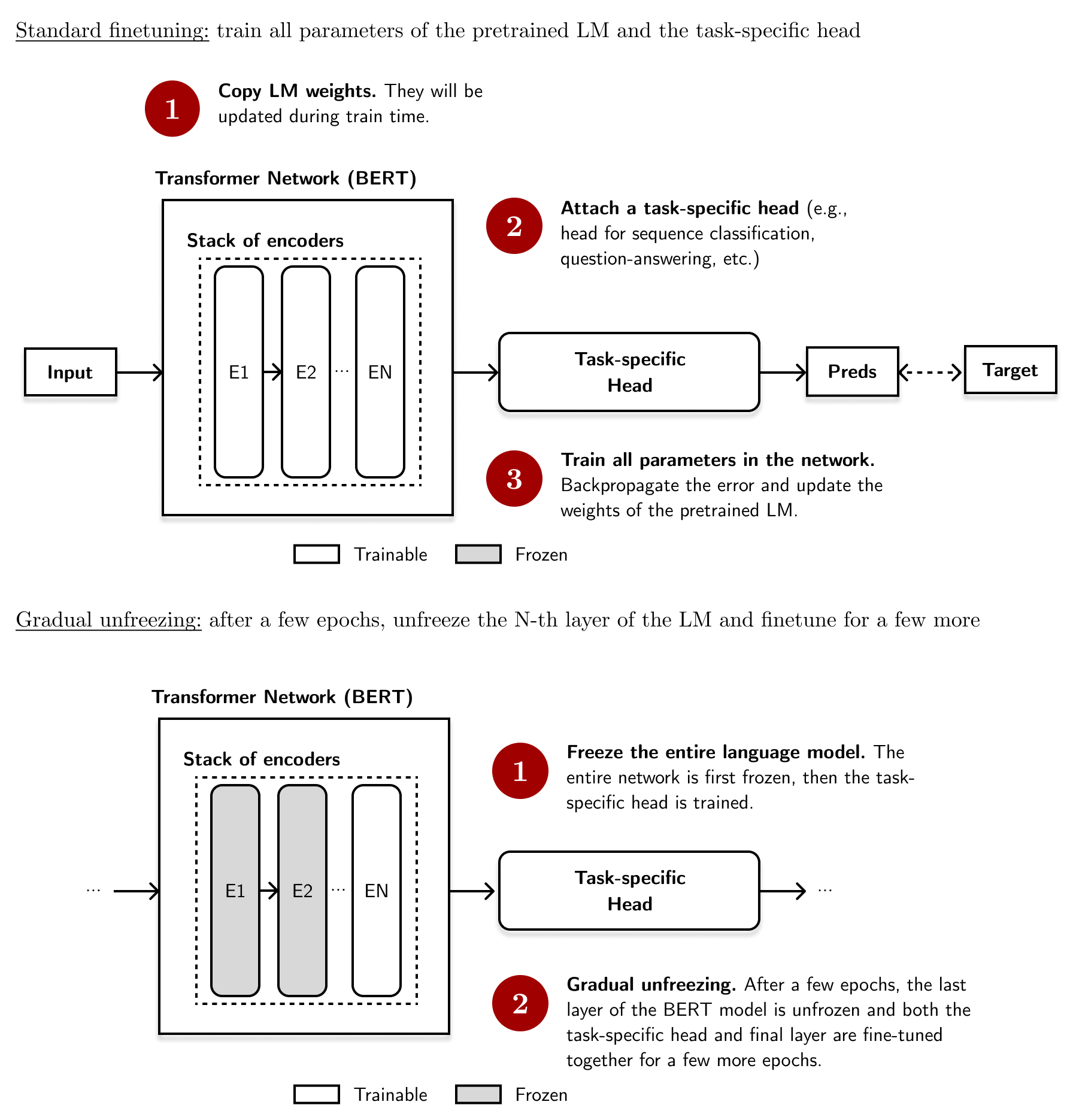

\[Feedforward(\mathbf{x}) = ReLU(\mathbf{x}\mathbf{W}_1 + \mathbf{b}_1)\mathbf{W}_2 + \mathbf{b}_2\]One common way to finetune is to attach a task-specific head at the end of a pretrained language model then train the entire network on our labeled data.1 Although these LMs were trained on different tasks (for example, BERT was trained on masked language modeling and next sentence prediction), it is possible to refine its weights for other NLP problems (e.g., sentence tagging, sequence classification, etc.).

However, this process has become inefficient (Treviso et al., 2023). The number of parameters in pretrained language models has increased exponentially, exacerbating fears in an LM’s environmental impact (Strubell et al., 2019) and making them inaccessible in resource-constrained and consumer-grade environments. Hence, an efficient approach to finetuning is becoming more desirable.

We can make the finetuning process more efficient and modular

Recently, I’ve been interested in parameter-efficient techniques (PEFT) that are modular in nature. Most of these involve creating small, trainable modules (sometimes a feedforward network or a special matrix) that we attach to different parts of a larger, pretrained network. Usually, we keep the larger network frozen while we train the smaller modules on our data.

Most [parameter-efficient techniques] involve creating small, trainable modules that we attach to different parts of a larger, pretrained network.

I like parameter-efficient and modular techniques because they appeal to my engineering sensibilities. I like the “separation of concerns” between our network’s fundamental understanding about language (pretrained network) and its task-specific capabilities (modular network), as opposed to training a single monolithic model. We can even aggregate these modules to solve multi-domain (Gurugangan et al., 2022; Chronopoulou et al., 2023; Asai et al., 2022; Pfeiffer et al., 2021) or multilingual problems (Pfeiffer et al., 2020; Pfeiffer et al., 2021).

I won’t be talking about every technique in this post. Instead, I’ll focus on methods that I like. For a more comprehensive overview, I highly recommend looking at Treviso et al.’s (2022) survey of efficient NLP techniques and Pfeiffer et al.’s (2023) work on modular deep learning.

- Adapters: attach small, trainable modules between transformer layers

- Prompt and prefix tuning: attach tunable parameters near the transformer input

- LoRA: decompose transformer weight updates into lower-rank matrices

Adapters: attach small, trainable modules between transformer layers

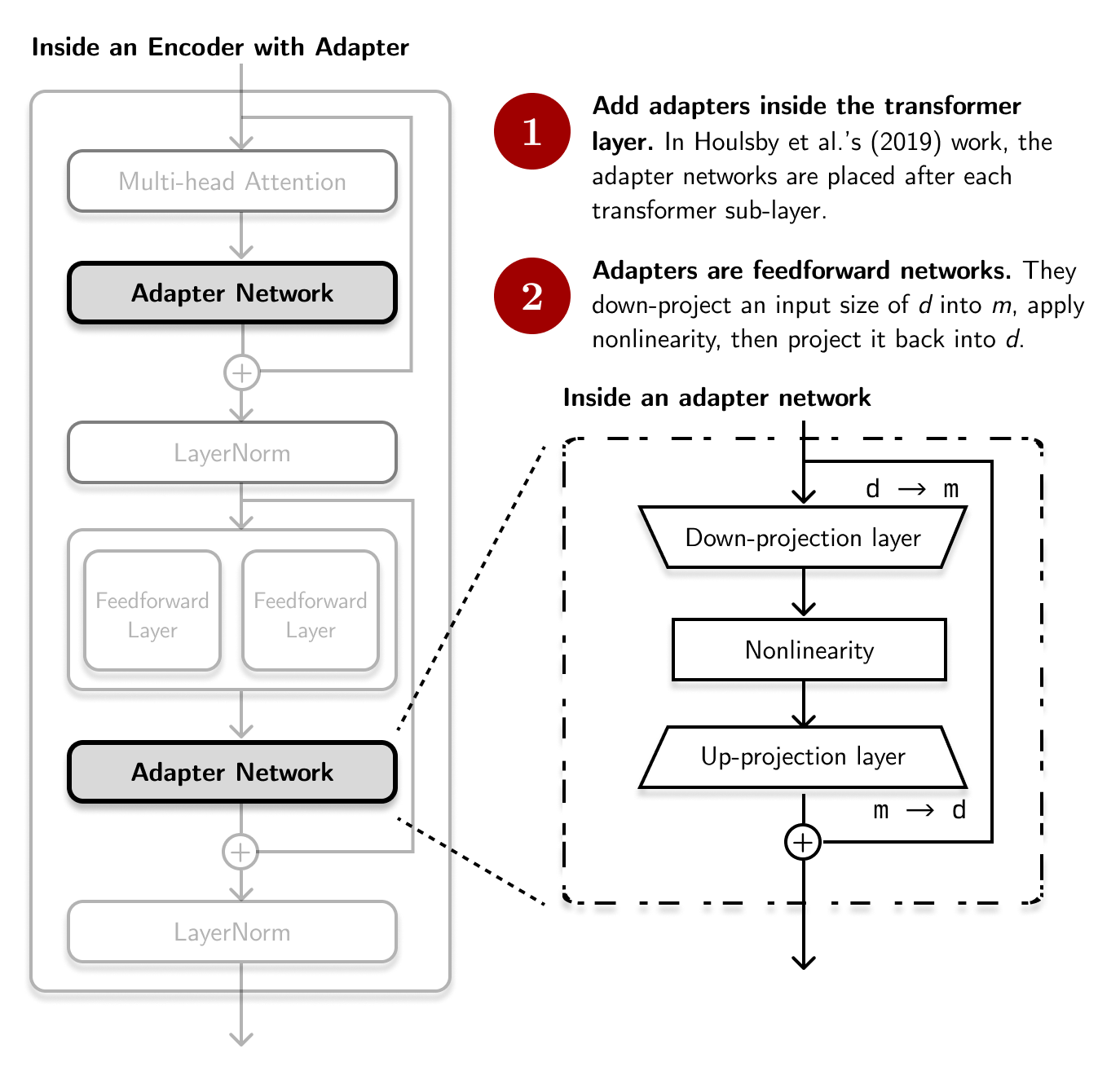

Houlsby et al. (2019) first proposed the use of adapters in the context of NLP. The idea is to attach a small feedforward network after each transformer sub-layer and tune it while keeping the larger network frozen:

# Pseudocode of a typical encoder layer with adapter

class EncoderWithAdapter:

def __call__(self, x: Tensor) -> Tensor:

residual = x

x = MultiHeadAttention(x)

x = AdapterNetwork(x) # Usually another feedforward layer

x = LayerNorm(x + residual)

residual = x

x = FeedForwardLayers(x)

x = AdapterNetwork(x) # Usually another feedforward layer

x = LayerNorm(x + residual)

return x

The adapter consists of a bottleneck architecture with a down- and up-projection, similar to autoencoders. It also contains an internal skip-connection. According to Houlsby et al. (2019), they were able to limit the number of trainable parameters to \(0.5-8\%\) of the original model.

# Pseudocode of an adapter network

class AdapterNetwork:

def __call__(self, x: Tensor, m: int) -> Tensor:

residual = x

d = get_dims(x)

x = DownProjection(input_dim=d, output_dim=m)

x = NonLinearity(x)

x = UpProjection(input_dim=m, output_dim=d)

return x + residual

From then on, researchers have proposed alternative adapter architectures. One notable development is from Pfeiffer et al. (2021), where they reduced the number of adapters significantly by attaching only one adapter per transformer layer with minimal performance degradation. Alternative adapter approaches also include training only the bias parameters as in BitFit (Ben Zaken et al., 2022), learning a task-specific different vector as in diff-pruning (Guo et al., 2021), or connecting adapters in parallel (He et al., 2022).

Most adapters consist of a bottleneck architecture with a down- and up-projection

However, I’m more interested in composing adapters together to solve multi-domain, multi-task, or multilingual problems.2 They add another level of flexibility to PEFT:

-

Multi-domain: For example, Chronopoulou et al. (2023) trained an adapter for each domain and computed its weight-space average at test time. They dubbed this as an AdapterSoup. The idea for “model soups” were based from Wortsman et al. (2022) and was inspired by convex optimization techniques.

-

Multi-task: Pfeiffer et al.’s (2021) work on AdapterFusion attempts to transfer knowledge from one task to another by combining their corresponding adapter representations. The “fusion” is done by introducing a new set of parameters \(\Psi\) (separate from the pretrained LM and adapter parameters, \(\Theta\) and \(\Phi\)) that learn to combine all the task adapters:

- Multilingual: The MAD-X framework (Pfeiffer et al., 2020) trains a language-specific adapter module via masked language modeling for the target language and a task-specific adapter module for the target task. This process enabled cross-lingual transfer given a pretrained multilingual model. They were also able to demonstrate its efficacy on languages unseen during the pretraining process.

The table below shows monolithic and modular techniques for each dimension of an NLP problem. Note that adapters still require a pretrained LM as its base, so don’t treat this as an either-or comparison.

| Dimension | Monolithic | Modular |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-domain | Most general-purpose BERT pretrained models | AdapterSoup (Chronopoulou et al., 2023), DEMix (Gurugangan et al., 2022) |

| Multi-task | MT-DNN (Liu et al., 2019) | AdapterFusion (Pfeiffer et al., 2021) |

| Multi-lingual | XLM-R (Conneau et al., 2019), Multilingual BERT (Devlin et al., 2018) | MAD-X (Pfeiffer et al., 2020), UNKs everywhere (Pfeiffer et al., 2021) |

There are still open problems I foresee with adapters. One is the complexity-efficiency tradeoff. It’s possible to “go crazy” in architecting adapters that the efficiency gain may not worth the complexity of the training set-up. Just like in engineering, there’s a tendency to go full-kubernetes when you can just use a simple virtual machine. I’m curious about the practical aspects of adapter training. I think AdapterHub is a good start. I’m still looking forward to developments in this field.

Prompt and prefix tuning: attach tunable parameters near the transformer input

Nowadays, the common way to leverage large-language models is through in-context learning via hard prompts (Brown et al., 2020). Take this prompt, for example, in a text classification task:

Determine whether the text below is a "Recipe" or "Not a recipe"

Text: """Add 2 cups of rice to 3 cloves of garlic, then

add butter to make fried rice"""

Answer: Recipe

Text: """I'm not sure if that will work"""

Answer: Not a recipe

Text: """To make a caesar salad, combine romaine lettuce,

parmesan cheese, olive oil, and grated eggs"""

Answer:

We refer to the text above as a hard prompt because we’re using actual tokens that are not differentiable (think of “hard” as something static or set in stone). The problem here is that the output of our LLM is highly-dependent on how we constructed our prompt. Language is combinatorial: it will take a lot of time to find the right “incantation” so that our LLM performs optimally. This begs the question: what if we can learn our prompts?

The problem [with in-context learning] is that the output of our LLM is highly-dependent on how we constructed our prompt.

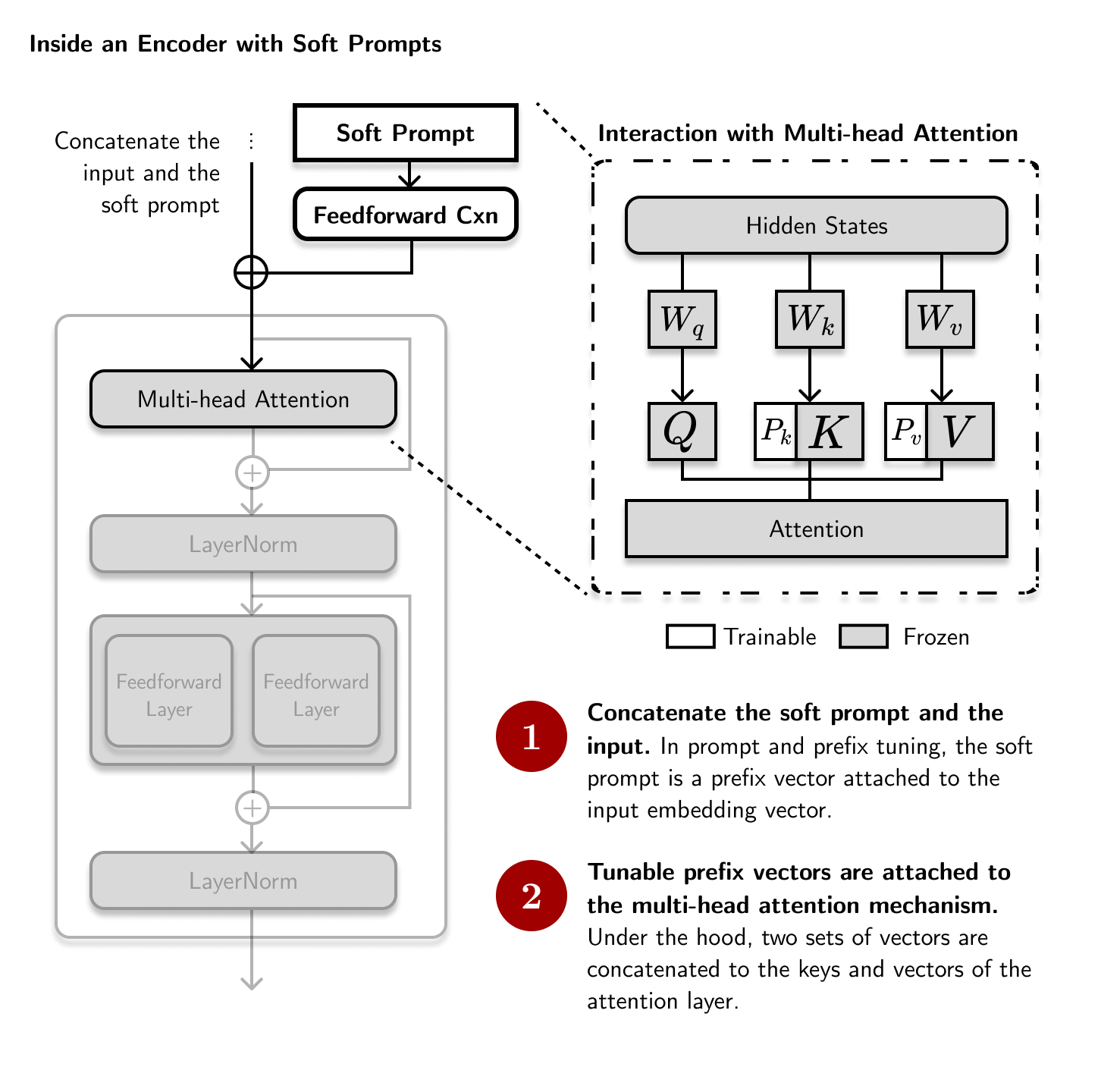

Prompt and prefix tuning solves this by making use of soft prompts— a vector attached to the input embedding that we train while keeping the pretrained LM frozen. These two ideas appeared at the same time (Lester et al, 2021; Li and Liang, 2021) but have similar mechanisms. The only difference is that prompt tuning adds the tensor only at the input while prefix tuning adds the tensor at each transformer layer:

# Pseudocode of a typical encoder layer with soft prompts

class EncoderWithSoftPrompts:

def __call__(self, x: Tensor, soft_prompt: Tensor) -> Tensor:

soft_prompt = FeedForwardLayer(soft_prompt)

x = concatenate([soft_prompt, x])

residual = x

x = MultiHeadAttention(x)

x = LayerNorm(x + residual)

residual = x

x = FeedForwardLayers(x)

x = LayerNorm(x + residual)

return x

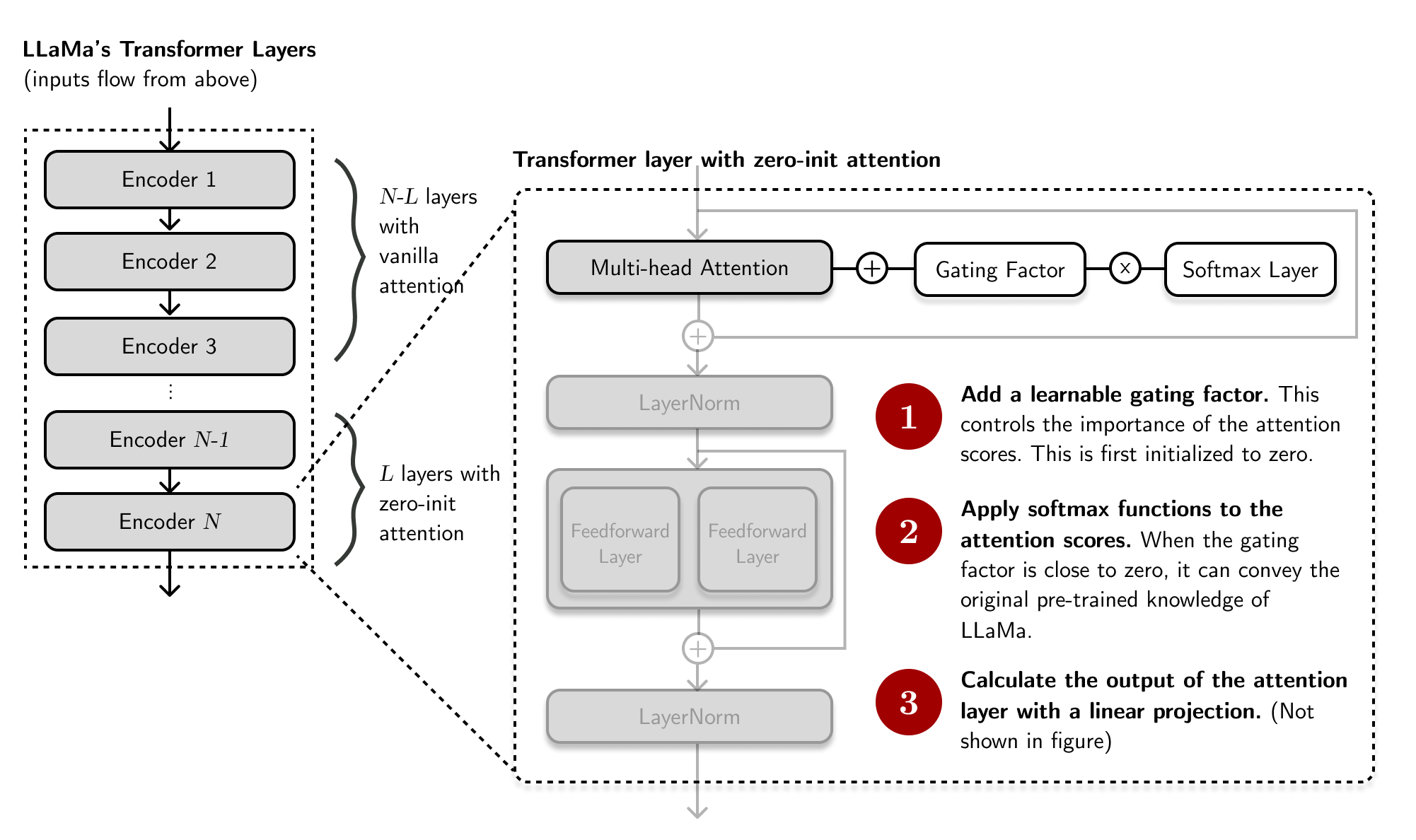

One of the currently popular implementations of prefix tuning is the LLaMa-Adapter (Zhang et al,. 2023). The mechanism is similar to prefix tuning with some subtle differences:

- Add prefix vectors only at the top-most layers: just like in prefix tuning, LLaMa adapter adds “adaption prompts” as prefix to the input instruction tokens. However, these prompts are only added at the \(L\) top-most transformer layers unlike in Li and Liang (2021) (top-most: the first layers affected by backpropagation).

- Zero-init attention with gating: here, the parameters near the attention mechanism are initialized to zero instead of at random. This process avoids unstable finetuning and “corruption” of LLaMa’s original knowledge.

I find these techniques (collectively known as p*-tuning) exciting because they open up different ways to update transformer inputs. I’m interested to examine, post-hoc, the dependency of these soft prompt weights to the data or domain. For example, we can probe these soft prompts to determine which parts of the input were most influential in generating the output (for both autoregressive and encoder-decoder networks). Lastly, I also find it exciting to seek ways to aggregate soft prompts together for multilingual applications.

LoRA: decompose transformer weight updates into lower-rank matrices

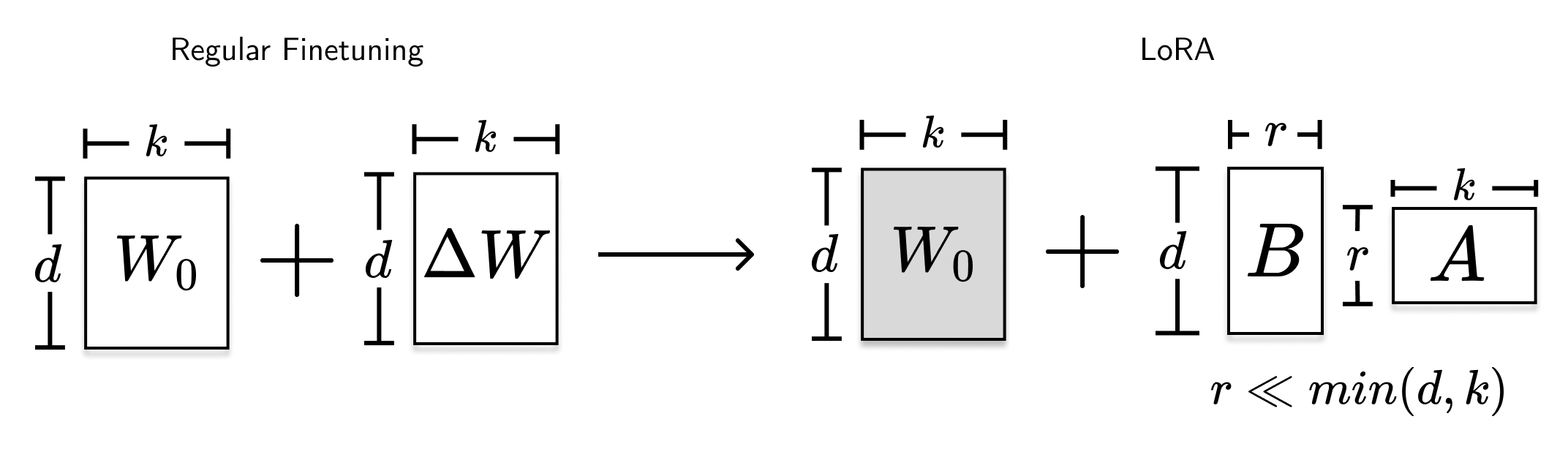

Lastly, Hu et al.’s (2021) work on Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) aims to make the weight update process more efficient. Their premise, based from Aghajanyan et al. (2021), is that although weight updates are of full-rank (each row and column are linearly-independent), they can still be represented into a lower-dimensional space while retraining most its structure (low-rank).

This technique is akin to using PCA or UMAP to reduce an n-dimensional (\(n>2\)) dataset into 2-d space in data visualization. In LoRA, we’re reducing the weight update matrix, \(\Delta W\). Note that we’re not really changing the shape of \(\Delta W\). Instead, we’re representing it into a low-rank form where redundancies are acceptable.

LoRA constrains the weight update \(\Delta W\) of a matrix \(W_0 \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times k}\) with two trainable low-rank matrices \(A\) and \(B\). This makes the weight update computation to be \(W_0 + \Delta W \rightarrow W_0 + BA\), where \(B \in \mathbb{R}^{d\times r}\) and \(A \in \mathbb{R}^{r \times k}\), \(r \ll min(d,k)\):

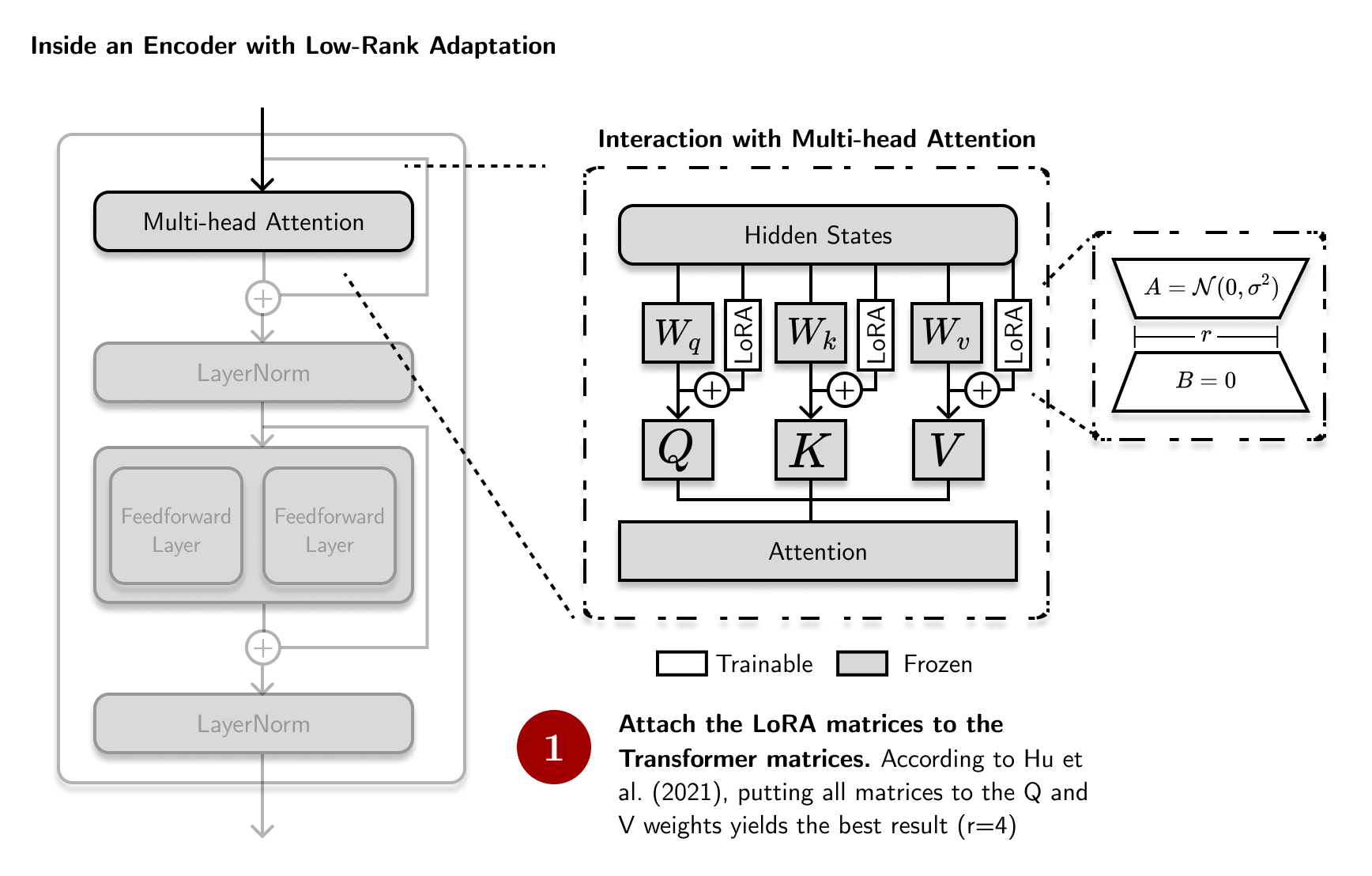

These \(B\) and \(A\) matrices are trainable. They used a random Gaussian initialization for \(A\) and zero for \(B\), so \(\Delta W\) is a zero-matrix at the beginning. Here, the rank \(r\) is a hyperparameter that must be tuned. In a transformer network, LoRA is applied to the attention weights:

I haven’t seen a lot of works that expand on LoRA or rank-decomposition as an efficient finetuning technique. However, I’m interested to perform more empirical experiments on this method, especially on figuring out where else we can attach these LoRA matrices. Interestingly, LoRA has found a foothold in image data, especially in diffusion networks (Rombach et al., 2021). Perhaps this technique can be extended into other modes of data.

Final thoughts

In this blog post, we looked into a few parameter-efficient finetuning techniques (PEFTs) for large language models. First, we had adapters, that attach small trainable modules between transformer layers. Then prompt and prefix tuning, that attach tunable parameters near the transformer input. Finally, we had low-rank adaptation that decompose transformer weights into lower-rank matrices.

It is interesting that despite their differences, there are structural similarities. Recently, I’ve been interested in reading papers that surmise a general framework for PEFTs. He et al.’s (2021) posits that PEFTs can be seen as clever weight updates on a transformer subspace. Pfeiffer et al. (2023) generalizes this further into what we now know as modular deep learning. In the application side, AdapterHub provides an implementation framework that allows users to leverage these PEFTs.

It is interesting that despite their differences, there are structural similarities between parameter-efficient finetuning techniques.

Finally, my interest in PEFTs are motivated by going against the current zeitgeist in NLP: train larger and larger models with larger and larger datasets. Perhaps there’s value in moving the other way around. Moving the needle in efficiency can lead to truly accessible and democratized NLP.

References

- Armen Aghajanyan, Sonal Gupta, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2021. Intrinsic Dimensionality Explains the Effectiveness of Language Model Fine-Tuning. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 7319–7328, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Akari Asai, Mohammadreza Salehi, Matthew Peters, and Hannaneh Hajishirzi. 2022. ATTEMPT: Parameter-Efficient Multi-task Tuning via Attentional Mixtures of Soft Prompts. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 6655–6672, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jimmy Lei Ba, Jamie Ryan Kiros, and Geoffrey E. Hinton. “Layer normalization.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.06450 (2016).

- Elad Ben Zaken, Shauli Ravfogel, and Yoav Goldberg. “Bitfit: Simple parameter-efficient fine-tuning for transformer-based masked language-models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.10199 (2021).

- Tom Brown, et al. “Language models are few-shot learners.” Advances in neural information processing systems 33 (2020): 1877-1901.

- Alexandra Chronopoulou, et al. “Adaptersoup: Weight averaging to improve generalization of pretrained language models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.07027 (2023).

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Suchin Gururangan, Mike Lewis, Ari Holtzman, Noah A. Smith, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2022. DEMix Layers: Disentangling Domains for Modular Language Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pages 5557–5576, Seattle, United States. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Demi Guo, Alexander Rush, and Yoon Kim. 2021. Parameter-Efficient Transfer Learning with Diff Pruning. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4884–4896, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Junxian He, et al. “Towards a unified view of parameter-efficient transfer learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.04366 (2021).

- Jeremy Howard and Sebastian Ruder. 2018. Universal Language Model Fine-tuning for Text Classification. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 328–339, Melbourne, Australia. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Neil Houlsby, et al. “Parameter-efficient transfer learning for NLP.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2019.

- Edward J. Hu, et al. “LoRA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685 (2021).

- Brian Lester, Rami Al-Rfou, and Noah Constant. 2021. The Power of Scale for Parameter-Efficient Prompt Tuning. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 3045–3059, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Xiang Lisa Li and Percy Liang. 2021. Prefix-Tuning: Optimizing Continuous Prompts for Generation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4582–4597, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jonas Pfeiffer, Andreas Rücklé, Clifton Poth, Aishwarya Kamath, Ivan Vulić, Sebastian Ruder, Kyunghyun Cho, and Iryna Gurevych. 2020. AdapterHub: A Framework for Adapting Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, pages 46–54, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jonas Pfeiffer, Ivan Vulić, Iryna Gurevych, and Sebastian Ruder. 2020. MAD-X: An Adapter-Based Framework for Multi-Task Cross-Lingual Transfer. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 7654–7673, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jonas Pfeiffer, Ivan Vulić, Iryna Gurevych, and Sebastian Ruder. 2021. UNKs Everywhere: Adapting Multilingual Language Models to New Scripts. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 10186–10203, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jonas Pfeiffer, et al. “Modular deep learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.11529 (2023).

- Jonas Pfeiffer, Aishwarya Kamath, Andreas Rücklé, Kyunghyun Cho, and Iryna Gurevych. 2021. AdapterFusion: Non-Destructive Task Composition for Transfer Learning. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, pages 487–503, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Robin Rombach, et al. “High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2022.

- Emma Strubell, Ananya Ganesh, and Andrew McCallum. “Energy and policy considerations for deep learning in NLP.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.02243 (2019).

-

Marcos Treviso, et al. “Efficient methods for natural language processing: a survey.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.00099 (2022).

- Vaswani, Ashish, et al. “Attention is all you need.” Advances in neural information processing systems 30 (2017).

- Zirui Wang, Zachary C. Lipton, and Yulia Tsvetkov. 2020. On Negative Interference in Multilingual Models: Findings and A Meta-Learning Treatment. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 4438–4450, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Mitchell Wortsman, et al. “Model soups: averaging weights of multiple fine-tuned models improves accuracy without increasing inference time.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2022.

- Renrui Zhang, et al. “Llama-adapter: Efficient fine-tuning of language models with zero-init attention.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.16199 (2023).

Footnotes

-

Note that it’s also possible to freeze the entire pretrained LM and only update the weights of the task-specific head. However, this process only works if the task-specific data is small to avoid overfitting. In most cases, updating both set of weights leads to better performance on the task at hand. ↩

-

NLP problems have multiple dimensions. Multi-domain: legal texts, finance documents, scientific publications, etc.; Multi-task: question answering, sequence classification, sequence tagging, etc.; Multi-lingual: English, German, French, etc. ↩