Your train-test split may be doing you a disservice

First, let’s recap a typical data science workflow: every project starts by splitting our data into train, development (dev), and test partitions. Then we fit our model using the train and dev sets and compute the score using a held-out test set.

Most of the time, we shuffle our data before splitting, creating random splits. For some benchmark datasets like MNIST or OntoNotes 5.0, these partitions are already included in the task, providing us with standard splits.

However, it turns out that random and standard splits can lead to test sets that are not wholly representative of the actual domain (Gorman and Bedrick, 2019, and Søgaard et. al., 2021). It’s also possible that the training and test sets look very similar, encouraging the model to memorize the training set without actually learning anything (Goldman et al., 2022). This behavior results in overestimated performances that don’t translate well into production.

It turns out that random and standard splits can lead to test sets that are not wholly representative of the actual domain…resulting into overestimated performance that don’t translate well into production.

This blog post discusses alternative ways to split datasets to provide more realistic performance. I will call all methods under this umbrella alternative splits. I’ll also investigate how alternative splits affect model performance on the named-entity recognition (NER) task using spaCy’s transition-based NER and the WikiNeural, WNUT17, and ConLL-2003 datasets.

| Dataset | Source | Description |

|---|---|---|

| WikiNEuRal (English) | WikiNEuRal: Combined Neural and Knowledge-based Silver Data Creation for Multilingual NER (Tedeschi, et al., 2021) | Dataset based from Wikipedia that takes advantage of knowledge-based approaches and neural models to create a silver dataset. |

| WNUT17 | Results of the WNUT2017 Shared Task on Novel and Emerging Entity Recognition (Derczynski, et al., 2017) | Dataset consisting of unusual, previously-unseen entities in the context of emerging discussions. |

| CoNLL 2003 | Introduction to the CoNLL-2003: Shared Task: Language-Independent Named Entity Recognition (Sang et al., 2003) | Standard NER Benchmark dataset where the English data was taken from the Reuters Corpus. It consists of stories between August 1996 and August 1997. |

We will discuss the following splitting methods:

- Spliting by maximizing divergence: where we try to find a combination of train and test splits that maximizes their differences. We’ll look into a work that uses Wasserstein distance and a k-nearest neighbor search to approximate the split.

- Splitting by heuristic: where we explore ways to split a dataset based on its characteristics. We will specifically look into splitting a document by its length and morphological features.

- Splitting by perturbation: where we examine how augmenting / perturbing the test set can lead to different model performances. Here, we’ll use an entity switch technique and replace entities with counterparts from a different country or locale.

I want to take this opportunity to introduce a Python package that I’m currently working on, ⚔️

vs-split. It’s still a work-in-progress, but it implements some techniques I’ll mention throughout the post.

Splitting by maximizing divergence

A central assumption in machine learning is that the training and test sets are from the same distribution, i.e., they are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) (Gilmer, 2020). But let’s drop that for a moment. We know that the i.i.d. assumption can lead to grossly overestimated model performances, but what if we evaluate the model with the “worst” possible test set?

We can obtain the “worst” test set by ensuring that the train and test sets have different distributions, i.e., they’re wholly divergent. In literature, this mode of splitting is called adversarial splits. We can measure this value using a metric called the Wasserstein distance. However, finding the right combination of train and test examples that maximizes this metric is an NP-hard problem, so Sogaaard et al. (2021) used an approximate approach involving k-nearest neighbors with a ball-tree algorithm.

If we run this method through the three datasets above, we can observe a short drop in test performance (measured by the Precision / Recall / F-score, lower values are highlighted):

| Dataset | Standard Split (P/R/F) | Wasserstein Split (P/R/F) |

|---|---|---|

| WikiNEuRal (English) | \(~0.87~/~0.86~/~0.87\) | \(\mathbf{0.82~/~0.79~/~0.81}\) |

| WNUT17 | \(0.47~/~0.45~/~0.46\) | \(\mathbf{0.41~/~0.25~/~0.31}\) |

| CoNLL 2003 (English) | \(0.86~/~0.86~/~0.86\) | \(\mathbf{0.87~/~0.84~/~0.85}\) |

Below you’ll find the displaCy output from ConLL 2003’s adversarial test split. I admit that I cherry-picked some of these examples, but one apparent pattern I saw is the presence of numbers (currencies, dates, scores) in the adversarial test set. One possible explanation is that the k-nearest neighbors search uses token counts as its feature, dividing the dataset based on token frequency.

-

Example 1: A text with unusual formatting. The way the text laid out the scores in this sports news article made it a bit incomprehensible.

-

Example 2: Financial text with a lot of currencies and dates. The WikiNEuRal dataset only has

PER,ORG,LOC, andMISCas its entity types. -

Example 3: Similar to the previous example, with dates, currencies, and other numerical text.

Splitting by heuristic

This section will discuss how we can split datasets using various heuristics such as a document’s length or morphological features. Unlike the previous approach, where we treat the splitting process as an optimization problem, “splitting by heuristic” takes advantage of domain-expertise to create an alternative test set.

Document length

For example, document length can be a valuable feature to gauge how well a machine learning model adapts to cross-sentence information in NER. Longer sentences can provide more context as to what type of entity a particular token is.

In the example above, we know that the token McKinley can refer to either a

location (LOC) or a person (PER). Because of the context sentence, “…was

named after William McKinley”, the model had a better idea of what type of

entity the second instance of McKinley is. The works of Luoma and Pyysalo

(2020), Arora et al. (2021), and

Siegelmann and Sontag (1992) explores how well NER models

can take advantage of such cross-sentence information.

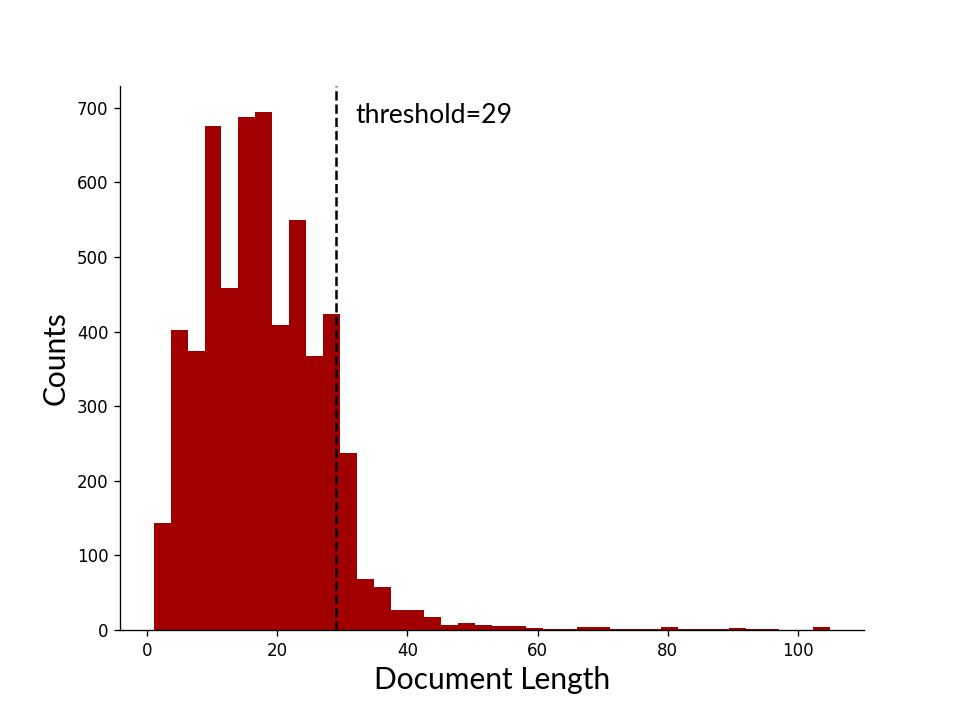

In our case, we’ll split the dataset so that the longer sentences are in the test split. Similar to Sogaard et al’s (2021) approach, we choose a threshold so that \(10\%\) of the documents will be found in the test set. After training a transition-based NER on this new split, the results are as follows (lower values are highlighted):

| Dataset | Threshold | Standard Split (P/R/F) | Split by Length (P/R/F) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WikiNEuRal (English) | \(38\) | \(0.87~/~0.86~/~0.87\) | \(\mathbf{0.84~/~0.85~/~0.85}\) |

| WNUT17 | \(29\) | \(\mathbf{0.47}~/~0.45~/~\mathbf{0.46}\) | \(0.58~/~\mathbf{0.42}~/~0.49\) |

| CoNLL 2003 (English) | \(446\) | \(0.86~/~0.86~/~0.86\) | \(\mathbf{0.78~/~0.84~/~0.81}\) |

It’s interesting why there’s not much change in the WNUT17 score. We can even say that the split improved the performance! I hypothesize that the token-length difference between the training and test is not that apparent given the distribution. This means that the split may not be as biased as we want it to be and just looks like a random split.

Here are some examples from the new WNUT17 test split:

-

Example 1: A text with token length 105. This document is one of the top 5 longest texts in the WNUT17 dataset.

-

Example 2: A text with token length 72. There seems to be an error in annotation. The text looks like a Tweet, but the token

@Xantecwas mislabeled as aproductinstead of aperson.

Morphological Features

We can also split datasets based on the presence of morphological features and inflections. Recall that words have a base form (lemma), whose structure changes (inflected) based on their role and function. For example, consider the sentence, “She was reading the paper,” if we run spaCy’s Morphologizer, we obtain:

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load("en_core_web_sm")

text = "She was reading the paper"

doc = nlp(text)

for token in doc:

print(token.text, " - ", token.lemma_, " - ", token.morph)

# She - she - Case=Nom|Gender=Fem|Number=Sing|Person=3|PronType=Prs

# was - be - Mood=Ind|Number=Sing|Person=3|Tense=Past|VerbForm=Fin

# reading - read - Aspect=Prog|Tense=Pres|VerbForm=Part

# the - the - Definite=Def|PronType=Art

# paper - paper - Number=Sing

The lemma, read, is modified into reading to express the progressive aspect

(Aspect=Prog), and the present tense (Tense=Pres). The same can be said to

the lemma, she, where it’s a third-person singular noun

(Person=3|Number=Sing) of the feminine gender (Gender=Fem).1

The idea then is that if we split a dataset based on its morphological

features, e.g., put all singular nouns (Number=Sing) or masculine gender

(Gender=Masc) in the training set; then perhaps we can better diagnose if our

models are robust against these inflections.

This is exactly what I did. By separating a few arbitrarily chosen features (I admit a lot of experimentation is still needed for this), I created a train-test split based on a document’s morphological inflections. In this case, I made sure that atleast \(10\%\) of the samples end up in the test set. The results are as follows (lowers values are highlighted):

| Dataset | Standard Split (P/R/F) | Morphological Split (P/R/F) |

|---|---|---|

| WikiNEuRal (English) | \(0.87~/~0.86~/~0.87\) | \(\mathbf{0.72~/~0.76~/~0.73}\) |

| WNUT17 | \(0.47~/~0.45~/~0.46\) | \(\mathbf{0.29~/~0.33~/~0.31}\) |

| CoNLL 2003 (English) | \(0.86~/~0.86~/~0.86\) | \(\mathbf{0.72~/~0.69~/~0.71}\) |

-

Example 1: A document from the new test set where tokens with a morph feature of

Gender=Femwere separated. -

Example 2: This is an interesting example because even if the majority of the sentence has a male-quoted text, it was still included in the test set because there’s no named entity for the masculine gender.

Splitting by perturbation

Lastly, we can split datasets by perturbing the test set. In this section, we’ll focus on entity switching or substituting specific entities with counterparts from a different locale or region. It is not strictly a split because we’re just updating entities. We may even consider this method a combination of the first two, i.e., applying heuristics to maximize the divergence between training and test sets.

Agarwal, Yang, et al. (2020) used this approach to audit the in-domain robustness of NER models. They replaced specific entities in the ConLL 2003 dataset with the same type but of different national origin. They discovered that some systems performed best in American and Indian entities and worst in Vietnamese and Indonesian entities. For example, using BERT subwords on ConLL 2003 reduced the NER F-score from \(94.4\) to \(88.2\) when using Vietnamese entities. It’s an interesting study that demonstrates how biased some NER systems are.

I tried replicating the entity-switched ConLL 2003 dataset they used, but I had difficulty reproducing them from their Github repository. So instead, I used the name-dataset library to get a random sample of Indonesian and Filipino names,2 then substituted them into our three datasets. Below are the results:

| Dataset | Standard Split (P/R/F) | Entity Switch (P/R/F) |

|---|---|---|

| WikiNEuRal (English) | \(0.87~/~0.86~/~0.87\) | \(\mathbf{0.85~/~0.82~/~0.83}\) |

| WNUT17 | \(\mathbf{0.47}~/~0.45~/~0.46\) | \(0.65~/~\mathbf{0.26}~/~\mathbf{0.37}\) |

| CoNLL 2003 (English) | \(0.86~/~0.86~/~0.86\) | \(\mathbf{0.86~/~0.79~/~0.82}\) |

Switching entities caused a drop in performance. Note that I’m not even precise

with how I substituted PERSON names, i.e., I didn’t consider if it’s a full

name or first name, and I didn’t regard the name’s gender. Nevertheless,

creating this split still caused issues with the transition-based NER parser.

Below is an example:

-

Example 1: A sports news report where all player names are replaced with Southeast Asian names. Note that the switch here doesn’t take context into consideration. The article mentions “Italy” but the names aren’t from that nationality.

Final thoughts

In this blog post, we examined the scenario where a typical train-test split may overestimate a model’s performance, thereby causing it to underperform in the wild. As it turns out, even standard NLP benchmarks can fall into this trap.

We then introduced three alternative splits: splitting by maximizing divergence, in this case by optimizing the Wasserstein distance, splitting by heuristics such as document length and morphological features, and splitting by perturbation, as illustrated by entity-switching. We tested these methods in three NER datasets to test spaCy’s transition-based NER system. We learned that robustness is still an issue given these benchmarks.

I think the best that we can do as machine learning practitioners is to create systems that allow checks and balances to ML systems. This might mean creating tools to measure robustness, reporting failure modes, and evaluating a model on a diverse set of samples. We’re still a long way to fully solve this problem, but acknowledging that it exists is a big step forward.

References

- Anders Søgaard, Sebastian Ebert, Jasmijn Bastings, and Katja Filippova. 2021. We Need To Talk About Random Splits. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, pages 1823–1832, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Kyle Gorman and Steven Bedrick. 2019. We Need to Talk about Standard Splits. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 2786–2791, Florence, Italy. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Omer Goldman, David Guriel, and Reut Tsarfaty. 2022. (Un)solving Morphological Inflection: Lemma Overlap Artificially Inflates Models’ Performance. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), pages 864–870, Dublin, Ireland. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Justin Gilmer. The Robustness Problem. Presentation slides at http://isl.stanford.edu/talks/talks/2020q1/justin-gilmer/slides.pdf

- Rob van der Goot. 2021. We Need to Talk About train-dev-test Splits. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 4485–4494, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Jouni Luoma and Sampo Pyysalo. 2020. Exploring Cross-sentence Contexts for Named Entity Recognition with BERT. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 904–914, Barcelona, Spain (Online). International Committee on Computational Linguistics.

- Ravneet Arora, Chen-Tse Tsai, and Daniel Preotiuc-Pietro. 2021. Identifying Named Entities as they are Typed. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, pages 976–988, Online. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Hava T. Siegelmann and Eduardo D. Sontag. 1992. On the computational power of neural nets. In Proceedings of the Fifth Annual ACM Conference on Computational Learning Theory, COLT 1992, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, July 27-29, 1992, pages 440–449. ACM.

- Oshin Agarwal, Yinfei Yang, Byron C. Wallance, Ani Nenkova. 2020. Entity-Switched Datasets: An Approach to Auditing the In-Domain Robustness of Named Entity Recognition Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.04123.

Footnotes

-

You can see the full taxonomy of morphological features in the UniMorph paper. ↩

-

I chose Filipino because the

name-datasetlibrary doesn’t contain Vietnamese names. Although Filipino names differ in structure (usually a Spanish or American first name followed by an English surname), they’re still in the Southeast Asian region, and it’s worth trying if Agarwal, Yang, et al.’s hypothesis still holds. ↩