Study notes on data-centric machine learning

Data-centric machine learning shifts the focus from fiddling model hyperparameters, to ensuring quality data across all. This post is a short review on various methods, approaches, and techniques to achieve this paradigm.

A few months ago, Andrew Ng launched his campaign for a more data-centric approach to machine learning. This meant having to move away from fiddling models to ensuring quality data across all. In line with this, he also started the Data-Centric AI competition, encouraging participants to increase accuracy by improving the dataset while keeping the model fixed.

Going into this direction is promising, as recent trends in the space encourage a data-centric approach:

-

We’re discovering pitfalls for being too fixated on models: achieving state-of-the-art (SOTA) with a model-centric approach incentivizes inane practices such as fixing random seeds and selective reporting (Henderson et al, 2019 and Lipton et al, 2019). Model results don’t often lead to understanding, as researchers treat accuracy as a score to be won, and even admit to practice HARK-ing (Bell et al, 2021 and Sculley et al, 2018).1 Inasmuch as researchers should correct these, perhaps a different problem-solving paradigm can also help.

-

Deep learning models are being democratized: hyperoptimizing models become less necessary due to the SOTA being more accessible. In NLP, the open-source community led by Huggingface and spaCy democratized Transformer models (Vaswani, 2017) to the public. In the private space, OpenAI has started offering access to their GPT-3 (Brown et al, 2020) APIs, while cloud platforms like Google has made AutoML available. Model-wise, it has become easier to be successful by just switching models or using a paid API.

-

ML is catching-up on software engineering practices: for the past year, we’ve seen the rapid growth of software tooling in the machine learning space. Dubbed as MLOps, software engineering and DevOps practices are being set up to support the ML lifecycle— we’re slowly paying off our technical debt (Sculley, et al, 2015). Albeit a nascent field, we’ve already seen tools geared towards data-versioning, “smart” labelling, and tracking.2 Data-centric machine learning is poised to take advantage of these developments.

In the industry, a data-centric approach is appealing. Data tend to have a longer lifespan and a larger impact surface area. Aside from using them as raw materials for training models, one can create other artifacts like dashboards or visualizations to drive important decisions. With the advent of open data, even just the act of storing and curating it is valuable enough. On the other hand, models are often susceptible to concept drift, and is only good on what it was built for (Tsymbal, 2004, Žliobaitė, 2010, and Sambasivan, 2021).

So what is the general strategy for data-centric machine learning?

Optimizing on what you have

Almost all data work, prior to modelling, revolves around two elements: (1) the domain-expert and (2) their data[set]. It is possible that one exists without the other, that’s why it’s important to optimize on what you have. If both exist, then we can think of their relationship as symbiotic:

Domain experts collect data, and in turn, data inform the expert (Gennatas, 2020). Both are enriched in the process: more data is provided, while the domain expert expands their knowledge of the field.3 This virtuous cycle generates insights and decisions for the organization.

From a modelling perspective, it is much better if the dataset is curated, i.e., it’s labeled. This means that meaningful information is attached to a given set of attributes. It then becomes straightforward to feed it into a machine learning model. In an ideal state, you have plenty of domain experts and labeled data. But in reality, organizations lack one or the other:

-

Little to no domain experts: it then becomes difficult to label everything with quality. In addition, one can fall into the trap of blindly applying ML techniques without the relevant insight and data quality assurance an expert can provide.

-

Little to no labeled data: this time, it’s challenging to train supervised models if the use-case demands for it. Labelling datasets can also become tedious, with or without the presence of domain experts. However, ML has progressed enough to understand unsupervised data, so it’s still possible to extract value on the given dataset.

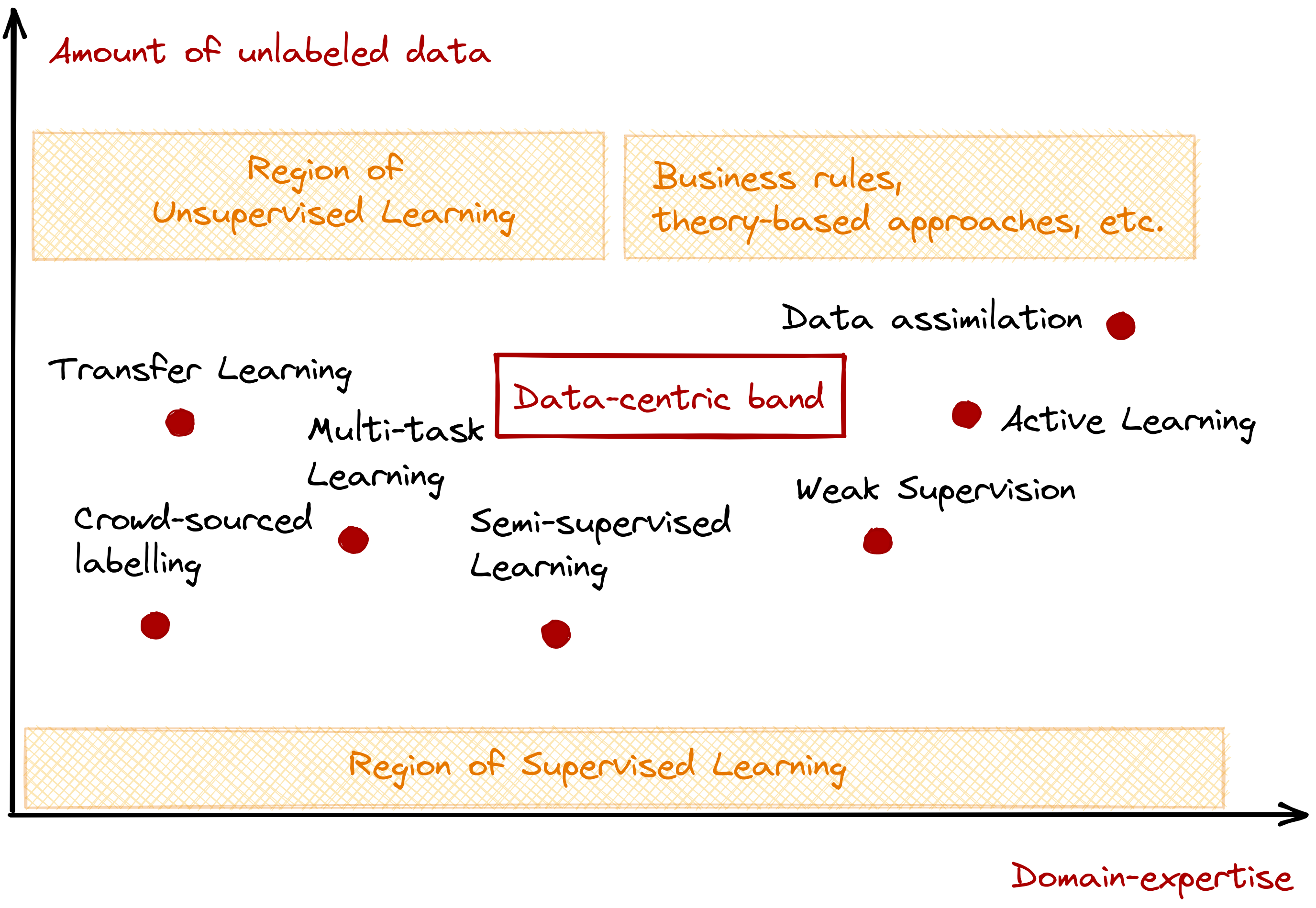

We can visualize their interaction in the graph below, with the x-axis representing the domain-expertise available for the problem, and the y-axis representing the amount of unlabeled data available. I also went ahead and plotted techniques that fall under each region:

Figure: Putting data-centric machine learning into context.

There’s a lot of moving parts, so let me describe each region:

-

Region of supervised learning: the number of unlabeled data is too low that it is straightforward to use a supervised learning approach. Note that this is viable even with the presence or absence of a domain-expert.

-

Region of unsupervised learning: the number of unlabeled data is too high that supervised learning techniques will either fail to generalize or are unusable altogether. Common unsupervised techniques involve clustering and dimensionality reduction, among many others.

-

Expert systems region: we still have a lot of unlabeled data, but we have access to domain-knowledge. Given that, creating rule-based expert systems may be better. Most process automation and document processing fall under this area. In addition, I also included theory-heavy, dynamic modelling approaches found in meteorology and financial engineering in this region.

-

Data-centric band (our focus): the problems encountered in this region do not only involve the type of model to use, but also the quality of data at hand. Here, you’ll find techniques that attempt to increase the number of labeled data, take advantage of domain expertise in modelling, and improve the quality of existing datasets.

There is a common misconception that machine learning is a binary choice between a supervised or unsupervised learning problem. Industrial machine learning rarely makes this decision easy. Oftentimes, machine learning problems exist within the data-centric band: datasets are messy, domain-experts may not be available, and labeled data is hard to come by.

In the next section, we’ll go over the techniques presented in the data-centric band. We’ll first look into those that do not require the presence of a domain-expert, then move towards more expert-driven approaches. Note that inasmuch as I want to be comprehensive in this review, I still limited the number of represented techniques for brevity.

Large unlabeled data, low domain-expertise

This may be the most common scenario in industrial machine learning: an abundance of unlabeled data with few experts to be found. If they exist, then the problem becomes about data collection and curation. We usually observe this in radiology, especially in datasets involving ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and X-ray (Masqood et al, 2019, Shin et al, 2016 and Byra et al, 2019).

We also encounter this problem in standard computer vision (CV) and natural language processing (NLP) tasks, moreso if the dataset isn’t similar to any of the benchmark ones.

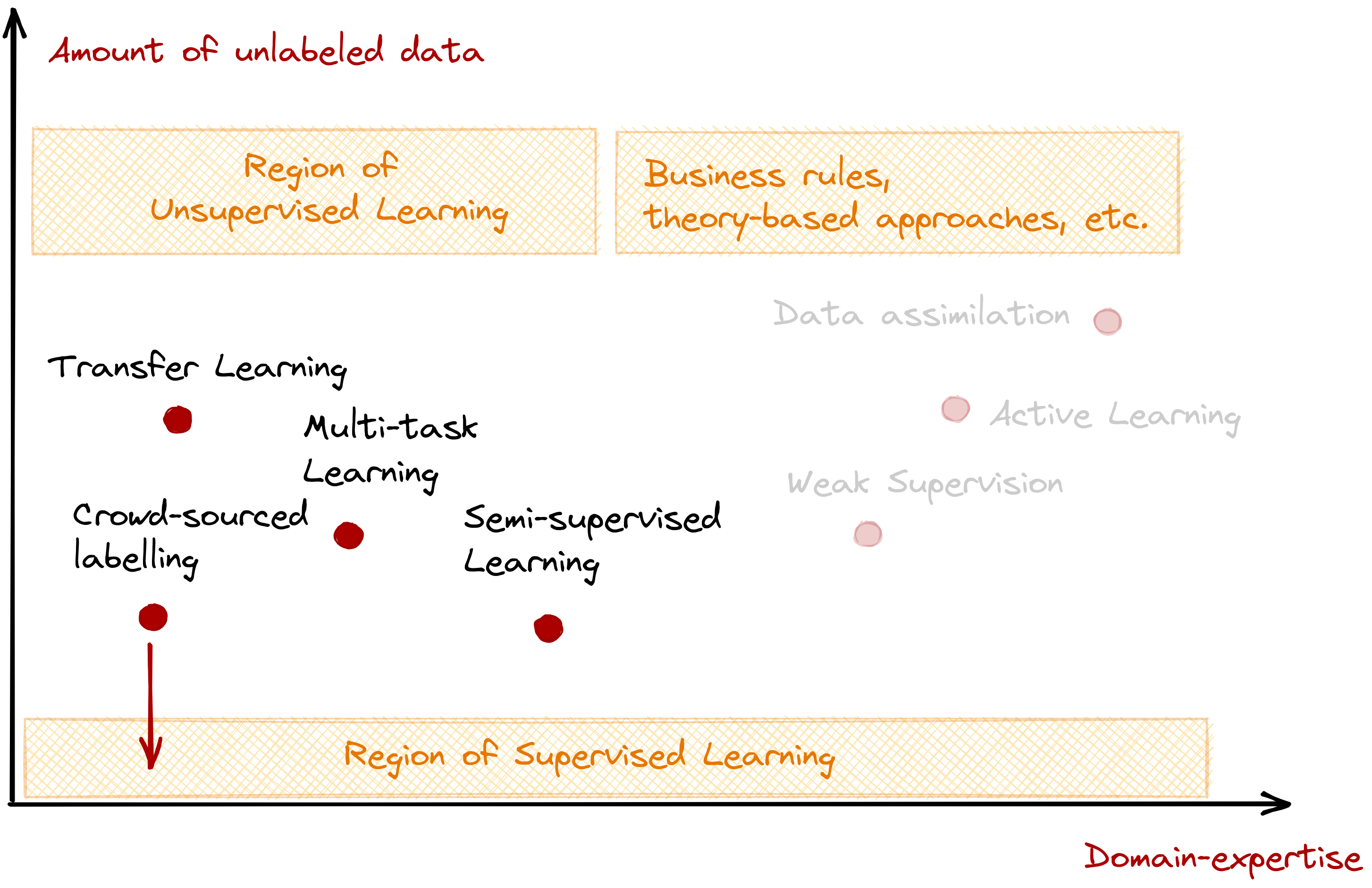

First, we’ll look into three model-based approaches: transfer learning, multi-task learning, and semi-supervised learning. All relax the dependency on labeled data by taking advantage of existing or solved tasks. In addition, we also have crowd-sourced labelling that aims to increase the amount of labeled data.

-

Transfer learning: involves the transfer of knowledge across domains or tasks. It challenges the common assumption that both training and test data should be drawn from the same distribution (Zhuang et al, 2020). Knowledge transfer can be in the form of instances, feature representations, model parameters, or relational knowledge (Pan and Yang, 2009).

A common use-case involves adopting an architecture like AlexNet (Krizhevsky et al, 2012), pretrainng it on ImageNet (Deng et al, 2009), and replacing the last fully connected layers with new ones from the target domain. The modified architecture is then finetuned on target domain labels for classification.

-

Multi-task learning (MTL): involves learning two or more related tasks simultaneously (Ruder, 2017b, Zhuang et al, 2020 and Crawshaw, 2020). Its goal is to “improve generalization by leveraging domain-specific information found in the training signals of related tasks (Caruana, 1997).” MTL works because it forces models to regularize via (implicit) data augmentation, focusing attention, eavesdropping, and adding representation bias (Ruder, 2017b).

There are two common setups for multi-task learning for deep neural networks: hard and soft parameter sharing. The former shares hidden layers across tasks where each task has its own output layer, while the latter constrains them using a cost function (Duong et al, 2015 and Yang and Hospedales, 2017).

-

Semi-supervised learning (SSL): is a combination of both supervised and unsupervised learning techniques. It takes advantage of the information found in the labels or cluster to improve performance (Zhu, 2005). For a supervised classification task, we use the implicit cluster information found from unlabeled data. For unsupervised classification, we harness the existing label-information found in the dataset (Van Engelen and Hoos, 2020).

SSL requires that the distribution of the input contains some information about its output (Van Engelen and Hoos, 2020). Moreover, it also assumes the following in our data (Chapelle, et al, 2006): neighboring points likely belong to the same class (smoothness), a decision boundary passes through regions with low-density (low-density), and that the input-space is composed of low-dimensional substructures (manifolds).

-

Crowd-sourced labelling: this approach doesn’t necessarily solve the data problem as-is. Instead, it moves us to a different position in the matrix, where a more straightforward solution like supervised learning can be applied. By tapping onto a large group, it is possible to obtain decent amounts of labeled data (Raykar et al, 2019). For example, Giuffrida, et al (2018) used a combination of citizen crowds and experts to classify a plant’s phenotype based on its image.

However, there is a tendency for a dataset (and consequently, the model) to be “polluted” due to the high variability of annotators (Della Penna and Reid, 2012 and Kajino, 2012). Thus, a labeling setup should be handled with as much care as possible. Common tools for crowd labelling involve cloud platforms such as AWS Mechanical Turk and Google’s Data Labeling Service.

Large unlabeled data, high domain-expertise

This section involves techniques that rely heavily on an expert’s domain knowledge to solve the data problem. Domain knowledge is still invaluable, and can find its use not only in model explainability (Biran and Cotton, 2017 and Doshi-Velez and Kim, 2017), but also in the collection and preparation of data (Yin et al, 2020).

An expert system is the outcome of extreme reliance to a domain expert. Unlike machine learning, rules are meticulously handcrafted instead of learned (Buchanan, 1989, Weiss and Kulikowski, 1991 and Ben-David and Frank, 2009). This approach may not always be scalable, especially at the sight of new data. However, because the rules are explicit, it is possible to justify and explain the system’s outcome.

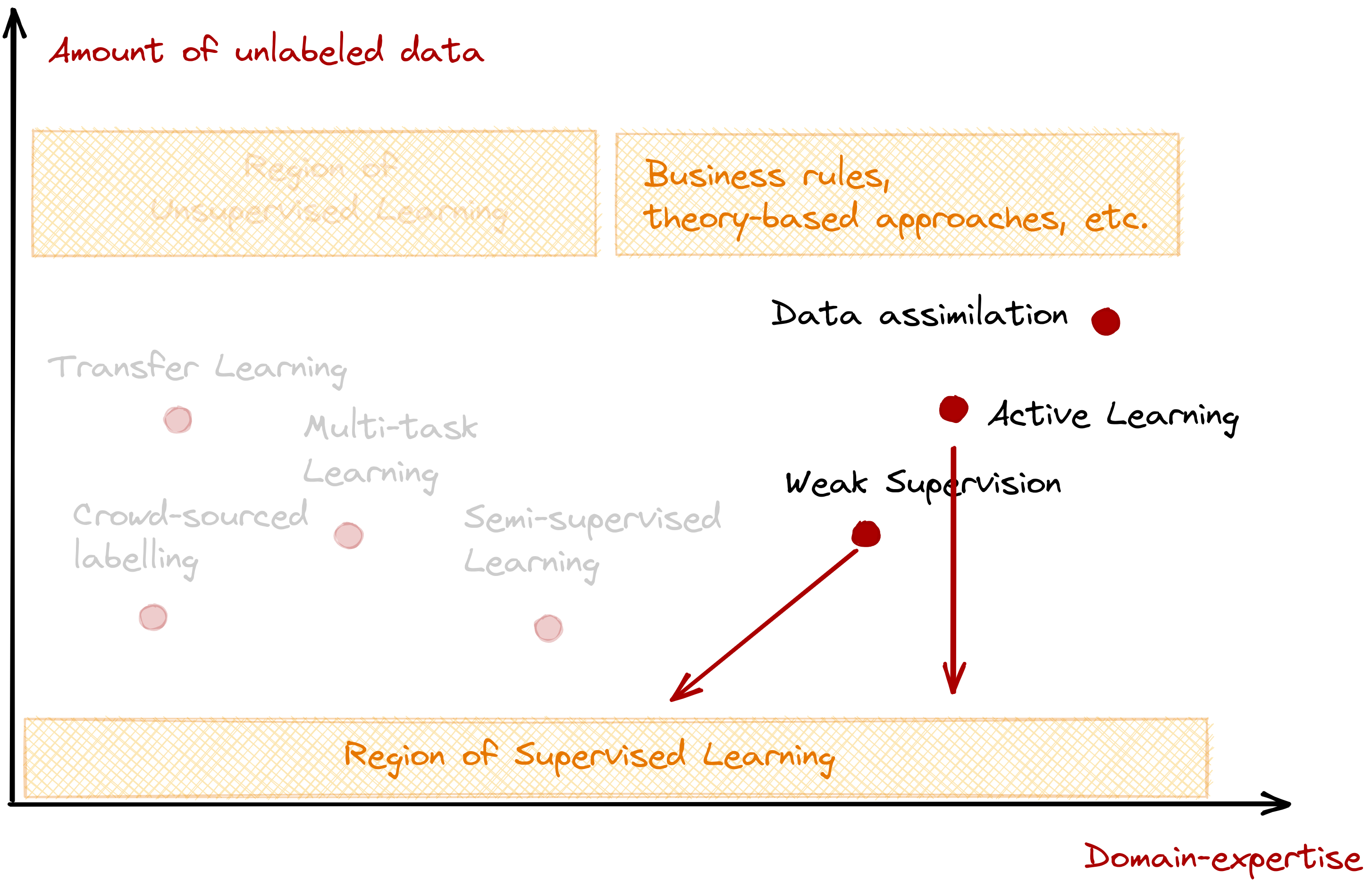

Here, you’ll see how a domain expert can contribute to crucial parts of the machine learning pipeline. For example, active learning and weak supervision tap domain knowledge to accurately and efficiently label relevant samples in the dataset, data augmentation seeks to add meaningful variation in the data to help create a robust model, and data assimilation aims to combine expert knowledge and a data-driven approach to build more accurate models.

-

Data assimilation (DA): combines theory with observations (Bouttier and Courtier, 2002). It is widely-used in meteorology and geosciences, particularly in weather prediction (Law et al, 2015 and Ghil and Malanotte-Rizzoli, 1991). Like machine learning, DA can also do forecasting, parameter optimization, and interpolation. However, the main difference is that DA utilizes a dynamic model of the system being analyzed. It combines data with mathematical models like Lorenz96 to describe phenomena.

Here, the domain-expert’s contribution is to determine the dynamic model that best describes their system’s behaviour. This may even be akin to “handcrafting the model.” However, not all problems have their equivalent model, putting favor to more data-driven approaches. Finally, there are efforts to combine machine learning and data assimilation (Brajard et al, 2020 and Abarbanel et al, 2018), and it will be interesting to follow their development.

-

Active learning: attempts to overcome the label bottleneck by intelligently asking a domain-expert (also known as oracle in active learning literature) to label select instances that will increase accuracy (Settles, 2009). The motivation is to have the learning algorithm choose the data from which it learns, thus lowering training costs (Cohn et al, 1996 and Settles, 2009). This can be achieved by query-strategies such as uncertainty sampling (Lewis and Gale, 1994), query-by-committee (Seung et al, 1992), and computing expected model change (Settles et al, 2007).

In reality, it turns out that the presence of a domain-expert is not a cure-all for the data problem. Settles (2011) highlighted some challenges when applying active learning in practice including lack of batch querying, noisy and unreliable oracles, and variable learning costs. Currently, examples of tools that endow active learning to their labelling workflow are Prodigy, SageMaker Ground Truth, and Dataiku.

-

Weak supervision: is a class of techniques where training data can be inexact, or innacurate (Zhou, 2018). Inexact samples occur when only coarse-grained information is provided. For example, predicting if a new molecule can make a special drug is based on its specific configuration. However, domain experts only know if a molecule is “qualified” to produce one, not necessarily which shape is decisive (Dietterich, 1997). One can solve this by explicitly asking the expert to “program” the training data, that is, create training functions to encode their business rules (Ratner et al, 2016 and Ratner et al, 2017). This type of “data programming” has been prevalent recently, with the rise of open-source tools like Snorkel.

As for inaccuracy, labeled samples are available but there’s no guarantee that they’re error-free. Even benchmark datasets like CIFAR-10 suffer from label inaccuracies (Beyer et al, 2020 and Northcutt et al, 2021a). Due to that, a sub-field called confident learning was developed to detect and correct such errors (Northcutt et al, 2021b). Its main mechanism involves pruning noisy data and ranking examples to train with confidence (Northcutt et al, 2017). Lastly, confident learning also exists as an open-source package, cleanlab.

Conclusion

In this blogpost, we reviewed different techniques towards data-centric machine learning. First, we looked into how recent trends motivate a different problem solving paradigm, then we focused our attention to the interplay betweeen a domain-expert and the dataset.

We then presented a simple graph that attempts to put each approach into context. We’ve seen techniques differ based on the presence of a domain-expert, and the amount of unlabeled data in the dataset. Moreover, we also defined regions based on traditionally known techniques: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and expert systems.

Lastly, the middle region in our plot represents the data-centric band, and we introduced what each technique does on a high level. We’ve seen methods that tap on the knowledge of domain experts, and techniques that take advantage of solved tasks. All of which improve the data we have at hand, leading to better models and high-quality data.

All in all, data-centric is a promising field. The techniques and approaches aren’t new— some of which have already existed back in the 90s, but it pays to know that simply maintaining a quality set of data will already give a decent set of returns than just mindlessly fiddling model hyperparameters.

@article{miranda2021datacentric,

title = {Towards data-centric machine learning: a short review},

author = {Miranda, Lester James},

journal = {ljvmiranda921.github.io},

url = {\url{https://ljvmiranda921.github.io/notebook/2021/07/30/data-centric-ml/}},

year = {2021}

}

Postscript

Phew! Writing this felt longer than usual. At first, I was inspired by the blogs of Lilian Weng and Sebastian Ruder, that I wanted to write a literature review of my own. I may have overdone it, as it spans a huge breadth of techniques under a large umbrella. Nevertheless, I’m happy with what I’ve written, and what you see here is a summary of my study notes in this space.

As for the topic, data-centric machine learning and the techniques involved in it piqued my curiosity. Insufficient samples, clerical errors, and unreliable sources are just a few among many challenges seen in industrial machine learning. Inasmuch as I wanted to approach it with tools and platforms that exist today, I am also excited to endow an academic approach to it, hence the tone.

Researching this took me a month and a half, mostly working on evenings and weekends. However, I had some practice writing very long-form content, as you may have seen in “Navigating the MLOps Landscape” and “How to use Jupyter Notebooks.” I’d probably do this again in the future, but I’ll definitely lower my scope.

References

- Abarbanel, H.D., Rozdeba, P.J. and Shirman, S., 2018. Machine learning: Deepest learning as statistical data assimilation problems. Neural Computation, 30(8), pp.2025-2055.

- Abu-Mostafa, Y.S., 1990. Learning from hints in neural networks. Journal of Complexity, 6(2), pp.192-198.

- Baxter, J., 1997. A Bayesian/information theoretic model of learning to learn via multiple task sampling. Machine Learning, 28(1), pp.7-39.

- Bell, S.J. and Kampman, O.P., 2021. Perspectives on Machine Learning from Psychology’s Reproducibility Crisis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08878.

- Ben-David, A. and Frank, E., 2009. Accuracy of machine learning models versus “hand crafted” expert systems–a credit scoring case study. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(3), pp.5264-5271.

- Beyer, L., Hénaff, O.J., Kolesnikov, A., Zhai, X. and Oord, A.V.D., 2020. Are we done with imagenet?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.07159.

- Biran, O. and Cotton, C., 2017, August. Explanation and justification in machine learning: A survey. In IJCAI-17 Workshop on Explainable AI (XAI) (Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 8-13).

- Bouttier, F. and Courtier, P., 2002. Data assimilation concepts and methods March 1999. Meteorological training course lecture series. ECMWF, 718, p.59.

- Brajard, J., Carrassi, A., Bocquet, M. and Bertino, L., 2020. Combining data assimilation and machine learning to emulate a dynamical model from sparse and noisy observations: A case study with the Lorenz 96 model. Journal of Computational Science, 44, p.101171.

- Brown, T.B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A. and Agarwal, S., 2020. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14165.

- Buchanan, B.G., 1989. Can machine learning offer anything to expert systems?. In Knowledge Acquisition: Selected Research and Commentary (pp. 5-8). Springer, Boston, MA.

- Byra, M., Wu, M., Zhang, X., Jang, H., Ma, Y.J., Chang, E.Y., Shah, S. and Du, J., 2020. Knee menisci segmentation and relaxometry of 3D ultrashort echo time cones MR imaging using attention U‐Net with transfer learning. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 83(3), pp.1109-1122.

- Caruana, R., 1997. Multitask learning. Machine Learning, 28(1), pp.41-75.

- Chapelle, O., Scholkopf, B. and Zien, A., 2006. Semi-supervised learning. 2006. Cambridge, Massachusettes: The MIT Press View Article.

- Cohn, D.A., Ghahramani, Z. and Jordan, M.I., 1996. Active learning with statistical models. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 4, pp.129-145.

- Crawshaw, M., 2020. Multi-task learning with deep neural networks: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.09796.

- Della Penna, N. and Reid, M.D., 2012. Crowd & prejudice: An impossibility theorem for crowd labelling without a gold standard. arXiv preprint arXiv:1204.3511.

- Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.J., Li, K. and Fei-Fei, L., 2009, June. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 248-255). IEEE.

- Dietterich, T.G., Lathrop, R.H. and Lozano-Pérez, T., 1997. Solving the multiple instance problem with axis-parallel rectangles. Artificial intelligence, 89(1-2), pp.31-71.

- Doshi-Velez, F. and Kim, B., 2017. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608.

- Duong, L., Cohn, T., Bird, S. and Cook, P., 2015, July. Low resource dependency parsing: Cross-lingual parameter sharing in a neural network parser. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (volume 2: short papers) (pp. 845-850).

- Gennatas, E.D., Friedman, J.H., Ungar, L.H., Pirracchio, R., Eaton, E., Reichmann, L.G., Interian, Y., Luna, J.M., Simone, C.B., Auerbach, A. and Delgado, E., 2020. Expert-augmented machine learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(9), pp.4571-4577.

- Ghil, M. and Malanotte-Rizzoli, P., 1991. Data assimilation in meteorology and oceanography. Advances in Geophysics, 33, pp.141-266.

- Giuffrida, M.V., Chen, F., Scharr, H. and Tsaftaris, S.A., 2018. Citizen crowds and experts: observer variability in image-based plant phenotyping. Plant Methods, 14(1), pp.1-14.

- Henderson, P., Islam, R., Bachman, P., Pineau, J., Precup, D. and Meger, D., 2018, April. Deep reinforcement learning that matters. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 32, No. 1).

- Kajino, H., Tsuboi, Y., Sato, I. and Kashima, H., 2012, July. Learning from crowds and experts. In Workshops at the Twenty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

- Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. and Hinton, G.E., 2012. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 25, pp.1097-1105.

- Law, K., Stuart, A. and Zygalakis, K., 2015. Data assimilation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 214.

- Lewis, D.D. and Gale, W.A., 1994. A sequential algorithm for training text classifiers. In SIGIR’94 (pp. 3-12). Springer, London.

- Lipton, Z.C. and Steinhardt, J., 2019. Research for practice: troubling trends in machine-learning scholarship. Communications of the ACM, 62(6), pp.45-53.

- Maqsood, M., Nazir, F., Khan, U., Aadil, F., Jamal, H., Mehmood, I. and Song, O.Y., 2019. Transfer learning assisted classification and detection of Alzheimer’s disease stages using 3D MRI scans. Sensors, 19(11), p.2645.

- Northcutt, C.G., Wu, T. and Chuang, I.L., 2017. Learning with confident examples: Rank pruning for robust classification with noisy labels. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.01936.

- Northcutt, C.G., Athalye, A. and Mueller, J., 2021. Pervasive label errors in test sets destabilize machine learning benchmarks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.14749.

- Northcutt, C., Jiang, L. and Chuang, I., 2021. Confident learning: Estimating uncertainty in dataset labels. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 70, pp.1373-1411.

- Pan, S.J. and Yang, Q., 2009. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 22(10), pp.1345-1359.

- Raykar, V.C., Yu, S., Zhao, L.H., Valadez, G.H., Florin, C., Bogoni, L. and Moy, L., 2010. Learning from crowds. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 11(4).

- Ratner, A.J., De Sa, C.M., Wu, S., Selsam, D. and Ré, C., 2016. Data programming: Creating large training sets, quickly. Advances in neural information processing systems, 29, pp.3567-3575.

- Ratner, A., Bach, S.H., Ehrenberg, H., Fries, J., Wu, S. and Ré, C., 2017, November. Snorkel: Rapid training data creation with weak supervision. In Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment. International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (Vol. 11, No. 3, p. 269). NIH Public Access.

- Ratner, A., Bach, S., Varma, P. and Ré, C., 2019. Weak supervision: the new programming paradigm for machine learning. Hazy Research. Available via https://dawn.cs.stanford.edu//2017/07/16/weak-supervision/. Accessed, pp.05-09.

- Ruder, S., 2019. Neural transfer learning for natural language processing (Doctoral dissertation, NUI Galway).

- Ruder, S., Aylien. The State of Transfer Learning in NLP [online]. 2019 [cit. 2019-08-19]. Available: https://ruder.io/state-of-transfer-learning-in-nlp/

- Ruder, S., 2017. An overview of multi-task learning in deep neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.05098.

- Ruder, S., Aylien. Transfer Learning: Machine Learning’s Next Frontier [online]. 2017 [cit. 2017-07-04]. Available: https://ruder.io/transfer-learning/index.html

- Sambasivan, N., Kapania, S., Highfill, H., Akrong, D., Paritosh, P. and Aroyo, L.M., 2021, May. “Everyone wants to do the model work, not the data work”: Data Cascades in High-Stakes AI. In proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-15).

- Settles, B., 2009. Active learning literature survey.

- Settles, B., Craven, M. and Ray, S., 2007. Multiple-instance active learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 20, pp.1289-1296.

- Settles, B., 2011, April. From theories to queries: Active learning in practice. In Active Learning and Experimental Design workshop In conjunction with AISTATS 2010 (pp. 1-18). JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings.

- Seung, H.S., Opper, M. and Sompolinsky, H., 1992, July. Query by committee. In Proceedings of the fifth annual workshop on Computational learning theory (pp. 287-294).

- Sculley, D., Holt, G., Golovin, D., Davydov, E., Phillips, T., Ebner, D., Chaudhary, V., Young, M., Crespo, J.F. and Dennison, D., 2015. Hidden technical debt in machine learning systems. Advances in neural information processing systems, 28, pp.2503-2511.

- Sculley, D., Snoek, J., Wiltschko, A. and Rahimi, A., 2018. Winner’s curse? On pace, progress, and empirical rigor. 1.a id=”shin2016computer”>Shin, H.C., Roth, H.R., Gao, M., Lu, L., Xu, Z., Nogues, I., Yao, J., Mollura, D. and Summers, R.M.</a>, 2016. Deep convolutional neural networks for computer-aided detection: CNN architectures, dataset characteristics and transfer learning. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 35(5), pp.1285-1298.

- Tan, C., Sun, F., Kong, T., Zhang, W., Yang, C. and Liu, C., 2018, October. A survey on deep transfer learning. In International conference on artificial neural networks (pp. 270-279). Springer, Cham.

- Tsymbal, A., 2004. The problem of concept drift: definitions and related work. Computer Science Department, Trinity College Dublin, 106(2), p.58.

- Van Engelen, J.E. and Hoos, H.H., 2020. A survey on semi-supervised learning. Machine Learning, 109(2), pp.373-440.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N., Kaiser, L. and Polosukhin, I., 2017. Attention is all you need. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03762.

- Weiss, S.M. and Kulikowski, C.A., 1991. Computer systems that learn: classification and prediction methods from statistics, neural nets, machine learning, and expert systems. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc..

- Weiss, K., Khoshgoftaar, T.M. and Wang, D., 2016. A survey of transfer learning. Journal of Big data, 3(1), pp.1-40.

- Yang, Y. and Hospedales, T., 2016. Deep multi-task representation learning: A tensor factorisation approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.06391.

- Yin, H., Fan, F. Zhang, J., Li, H., and Lau, T-F. The Importance of Domain Knowledge. [Available] In: https://blog.ml.cmu.edu/2020/08/31/1-domain-knowledge/

- Zhang, Y. and Yang, Q., 2017. A survey on multi-task learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.08114.

- Zhou, Z.H., 2018. A brief introduction to weakly supervised learning. National science review, 5(1), pp.44-53.

- Zhu, X.J., 2005. Semi-supervised learning literature survey.

- Zhuang, F., Qi, Z., Duan, K., Xi, D., Zhu, Y., Zhu, H., Xiong, H. and He, Q., 2020. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(1), pp.43-76.

- Žliobaitė, I., 2010. Learning under concept drift: an overview. arXiv preprint arXiv:1010.4784.

Changelog

- 10-14-2021: Include Neptune.ai on the list of data-versioning tools.

- 08-17-2021: This post was featured in DVC’s newsletter!

Footnotes

-

HARK-ing, refers to the research practice of hypothesizing after the results are known. Norbert Kerr defined it as “presenting a post hoc hypothesis in the introduction of a research report as if it were an a priori hypothesis” ↩

-

Examples of labelling tools: Prodigy, Snorkel, Label Studio. Examples of data-versioning and tracking (lineage) tools: MLFlow, DVC, Pachyderm, and Neptune.ai. ↩

-

That’s why I still think that ML practitioners who came from a non-ML field (psychologists, sociologists, economists, etc.) are at an advantage: they have an intimate knowledge of the field, and see ML as a tool. ↩