What are Nodes and Scenes in Godot? A cooking perspective

Introduction

Recently I’ve been learning game development in Godot, and one of my early barriers is understanding the idea behind Nodes and Scenes. What helped me get past this initial hump is by comparing it to something I usually do: cooking!

For me, cooking is about organizing ingredients into a more complex form. Put cooked rice, garlic, and butter in a pan, and you have yourself a nice breakfast sinangág (fried rice). You can compose and reuse ingredients— much like in programming.

In this blogpost, I’ll attempt to explain Godot’s Node-Scene system by comparing it to cooking. Specifically, I’ll focus more on the aspects of (1) composability and (2) reusability. Although it has been touched upon by the official documentation, I think that there’s still a lot that can be unpacked from it. Because I’m in a pasta craze right now, I’ll use Chicken Pesto Pasta, one of my favorite dishes, as an example!

Cooking employs composability

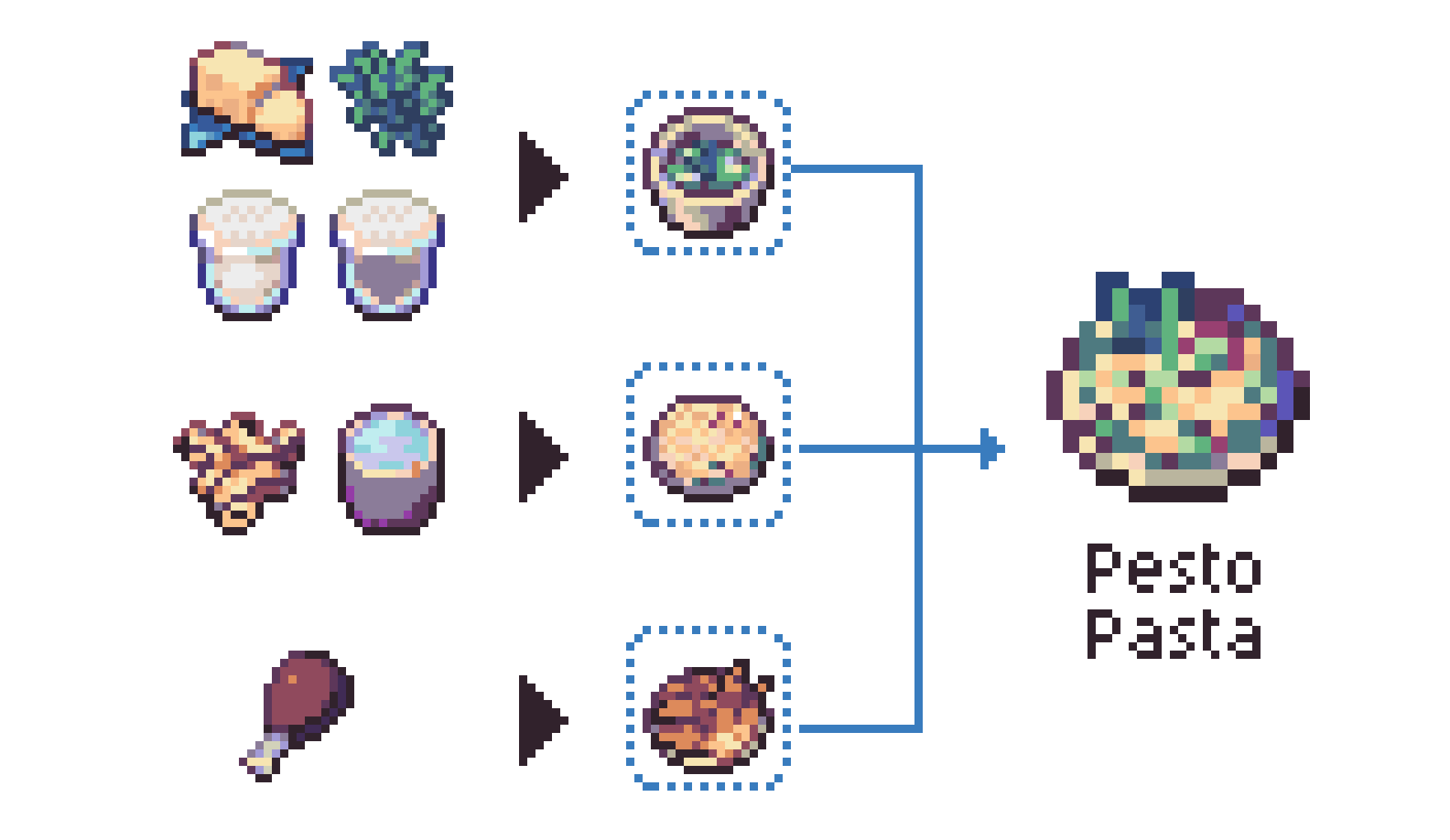

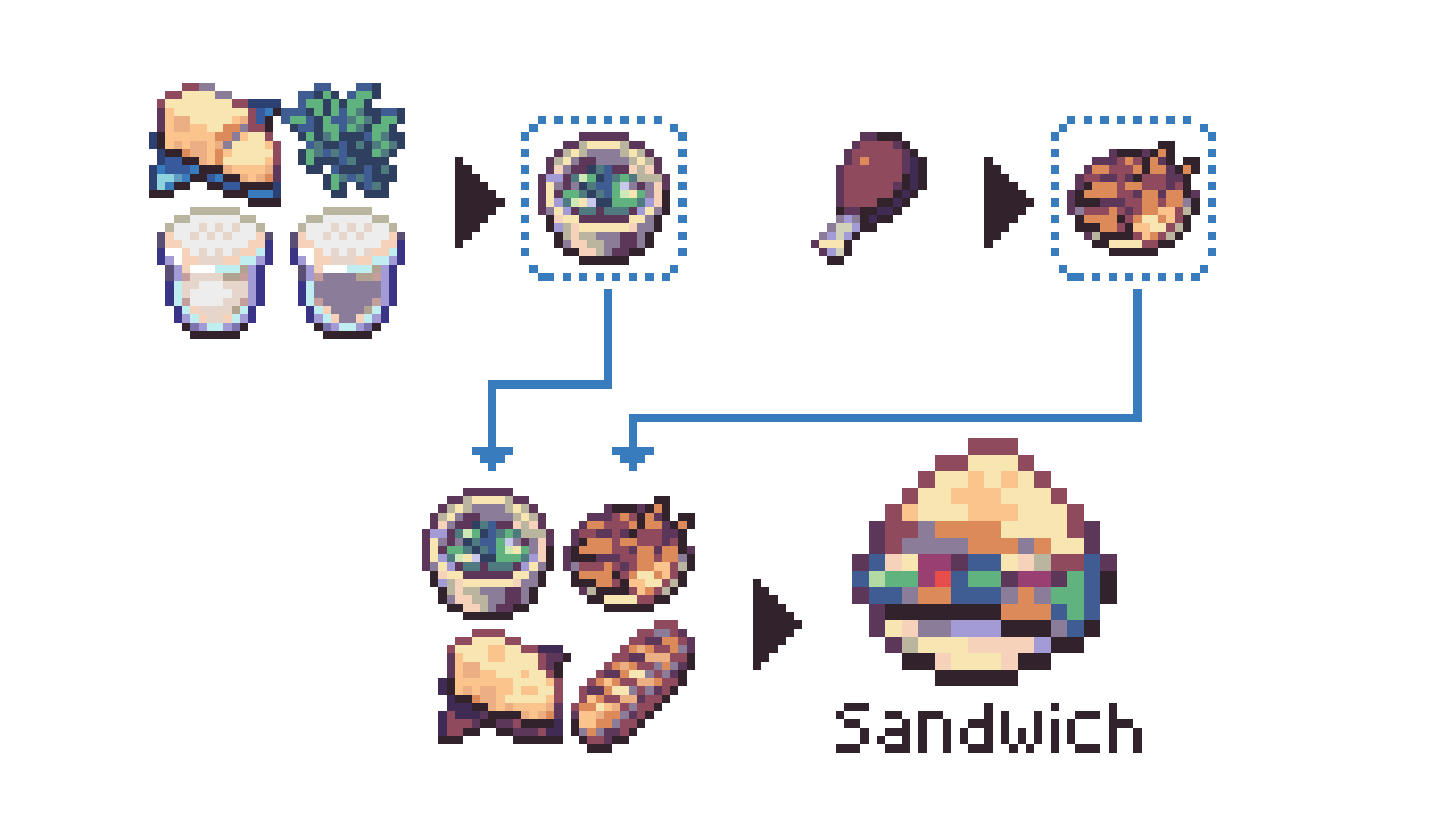

Cooking is hierarchical in nature, i.e, I can make an intricate dish by assembling basic ingredients together. For example, to make pesto sauce, I group basil leaves, salt & pepper, and butter in a pan (non-exhaustive)1:

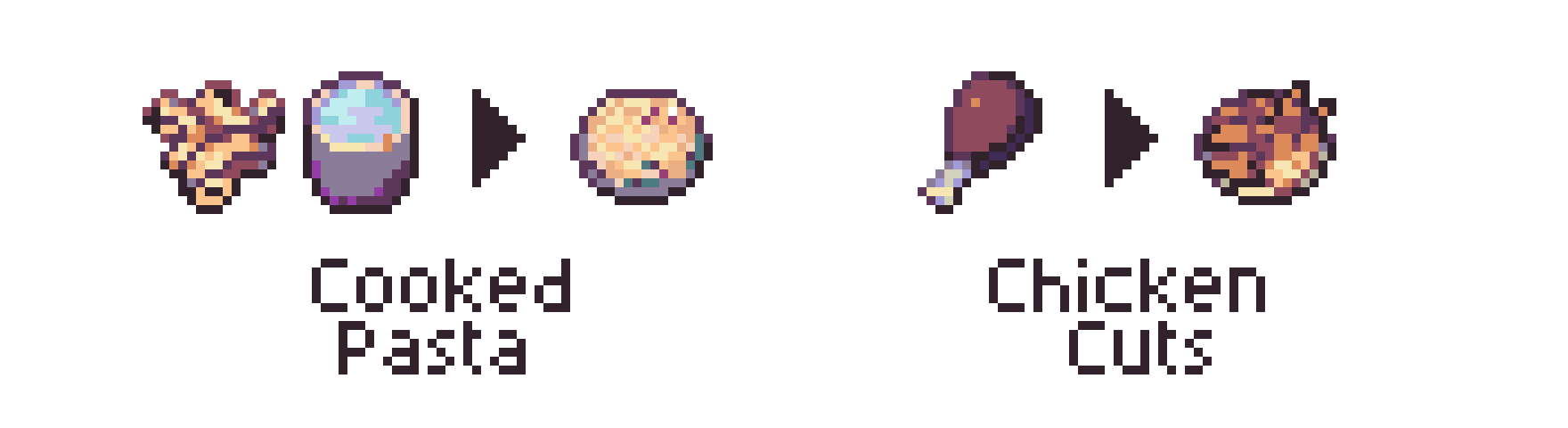

The same goes for cooked pasta and chicken-cuts:

So, the process of making chicken pesto can be thought of as iteratively combining one ingredient over the other. We start with primary ingredients (salt, paper, basil leaves, etc.) to make relatively complex ones (pesto sauce, chicken-cuts, pasta). Then, we arrange the latter for the final dish:

Composability is one of the core principles of Nodes and Scenes in Godot. Nodes can be thought of as the basic ingredients to build Scenes, a more complex ingredient particular to our dish. In our cooking example above, the pesto sauce, boiled pasta, and chicken-cuts—by nature of them being created from basic ingredients (nodes)—can be considered as our Scenes.

A word of caution

Contrary to the statement above, grouping nodes in a hierarchy doesn’t

necessarily result into a Scene. Depending on your use-case, a hierarchy of

nodes can also be another Node! To be more pedantic about it, Nodes can also

have children. This also threw me off when I was starting out (“so what makes

them different?”), but bear with my analogy for now. As you’ll see later

on, Scenes offer alot more than just hierarchy.

If we extend our analogy further, then Godot is a fully-stocked and fully-equipped Kitchen at our disposal. Enter the Kitchen and you’ll find almost any ingredient you can imagine: basil leaves, truffles, tuna, and more! Similarly, you’ll find Nodes for animating sprites, creating maps, displaying text, and more!

Godot is a fully-stocked and fully-equipped Kitchen at our disposal.

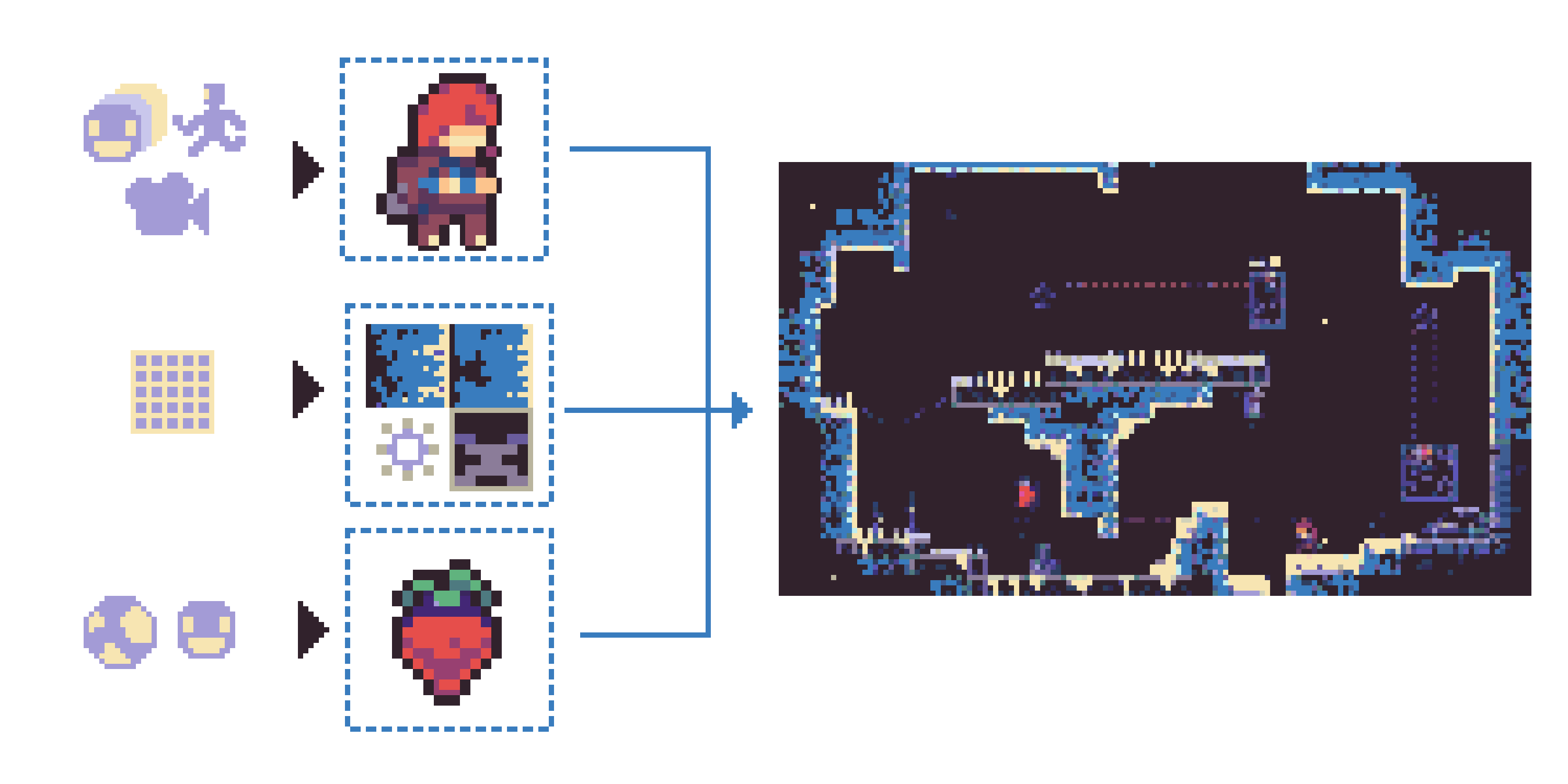

Now, let’s cook a 2D-platformer level. I’ll attempt to reconstruct a particular level from one of my favorite games, Celeste, from the Nodes found in Godot.

As usual, we take our basic ingredients (Nodes) from our kitchen (Godot) and organize them into groups (Scenes):

- For my Character, I’d mix an AnimatedSprite, KinematicBody2D, and a Camera2D.

- For my Map, I’ll use a TileMap.

- And for my Collectibles , I’ll have a Sprite and a RigidBody2D together

The list is by no means exhaustive. By combining the three together, we have produced a Level!2 We can then make more of these, assemble them with one another, and build a game!

This level of expressiveness makes Godot’s Node and Scene system powerful. We start from “low-level” primitives (Nodes), and assemble them into custom objects for our use (Scenes).

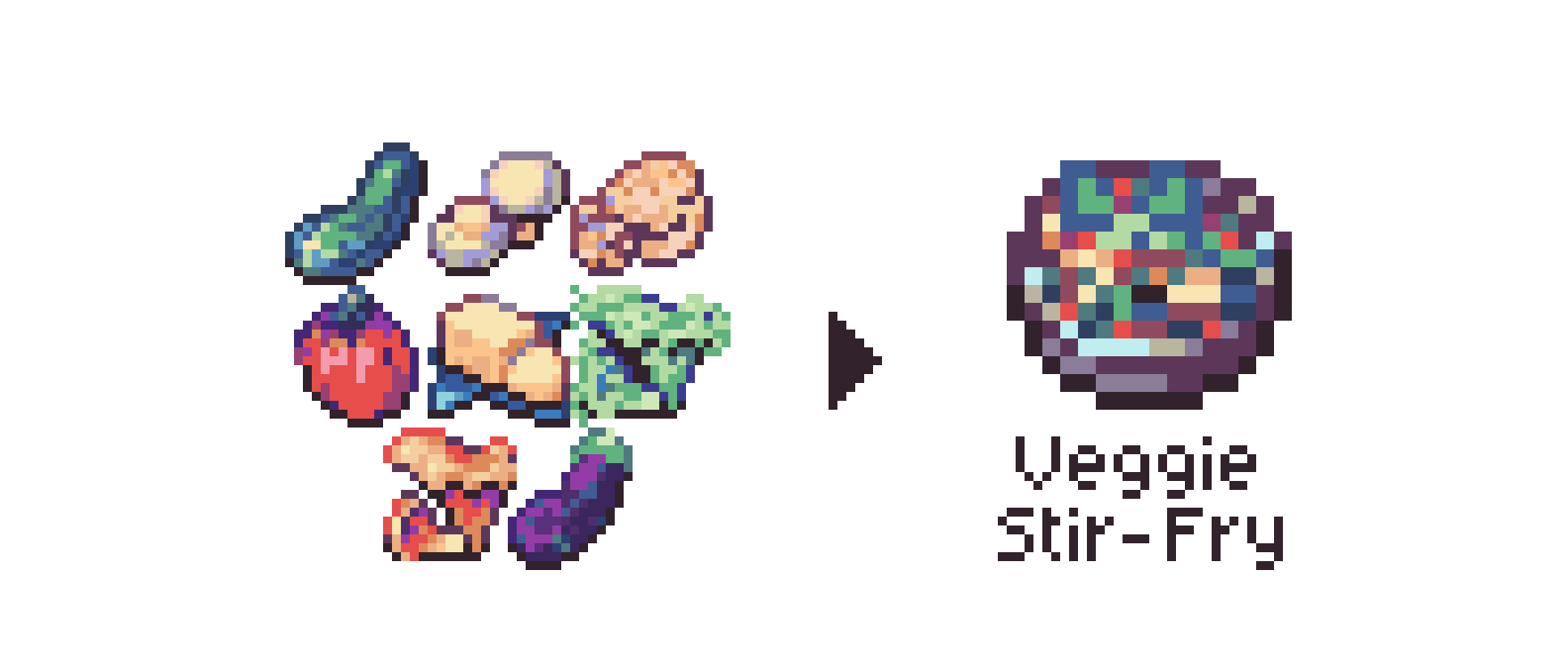

However, note that we can also express hierarchy by only using Nodes in a single Scene. I often find this similar to making stir-fry: you put everything into a pan and still make it work, but you need to be careful with your process. Same with Godot, putting everything into a single Scene may require you to rely upon your scripts and functions to achieve better encapsulation.

Whether to use the Single-Scene Pattern depends on your use-case: for smaller games, one Scene with multiple Nodes may be enough. Larger games may require better scene organization.

If we can also use Nodes for hierarchy, then what is the incentive for using Scenes? The answer is reusability. In the next section, I’ll discuss how we can use Scenes not just to group related nodes together, but also to reuse them and instantiate them whenever needed.

Cooking employs reusability

The best thing about pesto sauce and chicken-cuts is that I can use them for any other dish. After making a batch in the morning, I can keep them in a container, and store them in a fridge. If in the afternoon I start craving for a Grilled Chicken Pesto Sandwich, then I just take them out again and combine them with other ingredients (in this case, bread and cheese).

“Storing them in the fridge” and “taking them out again” is a key advantage that Scenes have over Nodes. I refer to this as reusability.

First, you can save Scenes into a disk, then, load them back again to instantiate whenever you need to. If I want to make a chicken sandwich, I don’t need to prepare the ingredients again; instead, I can just reuse the chicken-cuts that I made earlier.

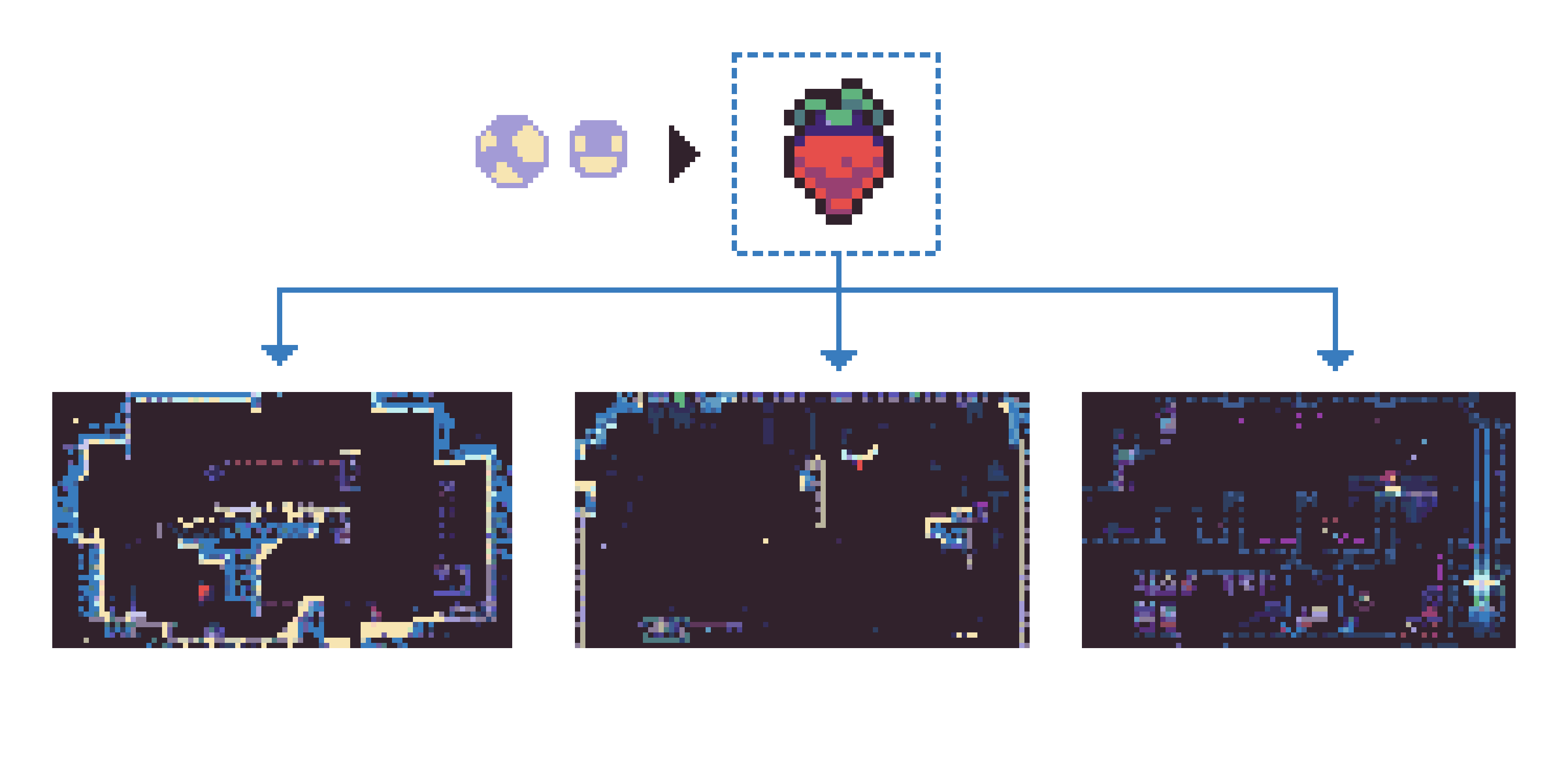

In the context of game development, we often see this pattern in Enemy mobs or collectible Items. First we prepare a template of an Item, and instantiate copies of it just in the time we’ll need them. In Celeste, the strawberry collectible appears in multiple areas of the game. We can implement this by creating a Strawberry template, and placing it on different areas of the map.

A word of caution

Of course, unlike our cooking example, we can virtually create infinite copies

of our Scene—only limited by our system memory. The batch of pesto sauce

that I created in the morning will run out, but the Scene I made in Godot can

be instanced as much as I want. I consider this as a limit of our cooking analogy.

With this insight, we can now think of Godot as a Scene Tree editor. Even a game made only with Nodes still belongs to a scene, i.e, the Main Scene or root node. Godot is powerful enough that we can customize a Scene’s behaviour during its lifecycle—when entering, when active, or when exiting the tree.

This mental model has also affected how I think about my projects in Godot. Before, I often start by asking myself, “what Nodes should I use for my game?”, treating them as a frame of reference. Now, it’s more about asking “what are the main components of my Game?”, where components are just Scenes. Since Scenes are reusable, I only need to “think” about these components once.

Since Scenes are reusable, I just need to “think” about [my game’s] component once.

In cooking, I also approach things from top to bottom. I start by decomposing a dish into its main components, e.g. sauce, meat, carbs, then figure out the basic ingredients needed to create them. There’s definitely alot of complexity involved, that’s why I always go back to my mother’s advice when cooking: start simple.

Mother’s cooking advice: start simple

So far, we’ve looked into how the concept of Nodes and Scenes resembles that of cooking:

- Nodes and Scenes are composable, you can combine basic ingredients (Nodes) together to form complex building blocks (Scenes) for your game.

- Scenes are reusable, I can just prepare an ingredient once, and instantiate every time I need it. There is no need for me to build a new Scene every time.

We’ve also seen how Godot can be likened to a fully-equipped Kitchen. There, we can find almost any ingredient to create almost any dish we can dream of. It’s powerful and fully-featured!

However, from my experience, too many features can be a tad overwhelming— it’s difficult to figure out where to start. Sometimes, I find Godot to be too flexible to a fault: there’s no enforced structure3, and it’s up to you whether to use Nodes or Scenes. It can be a boon for experienced game developers, but a bane for amateurs like me.

Sometimes, I find Godot to be too flexible ot a fault

At this point, I always go back to a cooking advice that my mom gives: start simple.

My first few attempts at cooking were as easy as putting things in a boiling pot (like sinigang or sour stew) or marinating meat (like adobo). There’s only one level of hierarchy required, and I don’t need too many ingedients: low complexity with minimal reusability.

Start simple: there’s only one level of hierarchy required, without the need of reusing any ingedients: low complexity with minimal reusability

I figure that this principle applies similarly in Godot. It is easier to start with one Scene, and just create Node hierarchies as you go along. By doing this many times over, I start developing an intuitive sense whether I need to convert a node tree into a Scene. Godot makes it simple to do so: just Right-click a Node in your viewer, and “Convert Branch into a Scene”

And indeed, from my three years of software engineering experience, it is usually easier to move from simplicity to complexity than the other way around. Start with simple concepts, then add layers of abstraction as you go. Like cooking, just start by putting stuff into a pot, and later on you’ll see yourself preparing more complex dishes.

Conclusion

In this blogpost, I compared the concept of the Node-Scene system in Godot to the activity of cooking. From what we’ve seen, both exhibit:

- Composability, similar to combining ingredients together to form a complex dish, we also combine Nodes to form Scenes, and Scenes to build our Game; and—

- Reusability, similar to preparing a batch of ingredients early on and reusing them for different dishes, I can also prepare a Scene and instantiate it whenever needed.

I also mentioned that if the Node-Scene system is like cooking, then Godot is like a fully-stocked Kitchen. We enter and find almost any ingredient we can imagine, from animating sprites to simulating 3d physical objects. It’s a well-supplied Kitchen at our disposal.

This then brought us to our final point: start simple. Navigating a large Kitchen can be overwhelming, so just like what my mother said, it’s OK to start by putting things in a boiling pot. Start simple, and add complexity whenever necessary.

I hope that you’ve learned something from this simple analogy. I find similar joy in cooking and making games: sometimes I do them for myself, sometimes I do them for others. There’s a similar anticipation in asking, “So, what do you think?”, after someone tasted a dish or play-tested a game. To be honest, I’m still not ahead in my game-dev and cooking journey, so there’s still a lot to learn— exciting!

Let me know your thoughts and questions in the comments below!

References

- J. Linietsky and A. Manzur, “Godot Docs – 3.2 branch,” Godot Engine documentation. [Online]. Available: https://docs.godotengine.org/en/stable/index.html. (Accessed: 15-Apr-2021).

- “Overall scene tree organization,” Reddit. [Online]. (Accessed: 15-Apr-2021). Reddit user u/willnationsdev had an enlightening comment on how to differentiate between scripts, nodes, and scenes. The discussions here are also good, and helped clear-out some of my remaining confusion.

- “Struggling with the difference between scenes and nodes,” Reddit. [Online]. (Accessed: 15-Apr-2021). Upon learning that their difference is arbitrary, it felt a bit freeing. Turns out there are no hard and fast rules to use Nodes vs. Scenes.

Changelog

- 04-23-2021: This blogpost was featured in Issue 30 of This Week in Godot!

- 04-19-2021: Update some grammar and usage issues

-

I’m currently learning iconography and a particular style of coloring in pixel art— so please be nice! Trying to move away from the standard PICO-8 palette that I’m used to. Thanks a lot to OpenGameArt for providing some useful references, and the Comfort44s palette for the colors! ↩

-

Of course, it’s not as simple as that. We still need to wire-up the parts properly and write the logic on how these things work together. I decided not to talk about it because it may be outside the scope of my topic. ↩

-

Fortunately, the Godot documentation offers some best practices when organizing Scenes. I highly-recommend going through them, although I still find it hard to parse these ideas (seems to cater to more intermediate developers). ↩