Desiderata for Filipino NLP in the Age of LLMs

Back when I started working in Filipino NLP, my standard approach in training models is to encode linguistics knowledge via meticulous data annotation, feature engineering, and extensive testing. Take calamanCy for example: we spent countless hours annotating named-entity recognition (NER) datasets and validating dependency parsing treebanks to train statistical models using frameworks like spaCy. Back then, these components typically power larger systems that handle tasks like information extraction and question answering. But lately, we’ve seen how LLMs can tackle these tasks end-to-end, without needing any of these components at all.

The pace of progress in multilingual LLMs has also been relentless this year. We’ve seen several high-profile releases such as Meta’s Llama 3.1, Cohere for AI’s Aya Expanse, and Southeast Asian models such as AI Singapore’s SEA-LION and Sea AI’s Sailor. Sure, one can still argue that building custom-made pipelines is still viable because current LLMs don’t always work well on Filipino (and I’ve argued these before [1] [2]) and that there are advantages in building modular, non-black box components, but the impressive gains in multilinguality from data scale have changed my perspective somewhat.

While I still believe in building artisanal Filipino NLP resources, I now see that we need to simultaneously support the development of multilingual LLMs by creating high-quality Filipino datasets and benchmarks. This way, we can actively push for the inclusion of Philippine languages in the next generation of multilingual LLMs, rather than just waiting for improvements to happen on their own.

We need to focus on creating high-quality datasets and evaluation benchmarks [to] actively push for the inclusion of Philippine languages in the next generation of multilingual LLMs.

Filipino is still left behind even in the age of LLMs (more on this later). Sometimes I feel a tinge of sadness when a research group releases a new multilingual LLM and Filipino is not supported. You can’t blame them— there’s not a lot of readily-available Filipino data for LM training and evaluation. This is even true for other Philippine languages such as Hiligaynon, Kapampangan, and Ilokano. There are still missing pieces ripe for research.

In this blog post, I want to talk about three actionable directions for Filipino NLP: (1) create resources that support LLM post-training, (2) build reliable benchmarks for Filipino, and (3) participate in grassroots research and annotation efforts. Also, if you are interested to collaborate in these types of efforts, feel free to reach out!

Create resources that enable LLM post-training

Key Insight: Better to focus on post-training since it requires relatively lower investment than pretraining. Prioritize collecting instruction finetuning datasets since it’s in this step where we usually observe significant performance gains. Better if they contain general chat, but domain-specific data should also work.

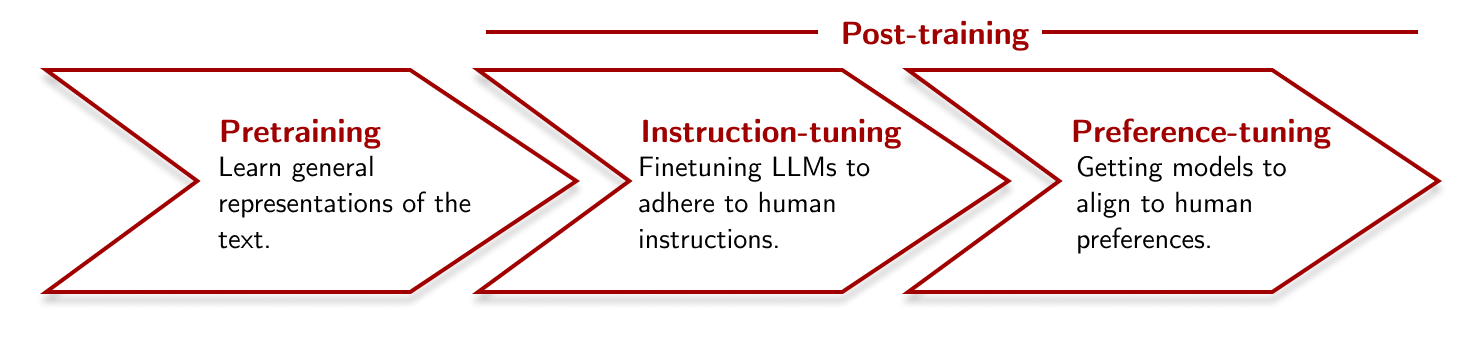

Post-training is the stage in the large language modelling pipeline where we adapt a pretrained model to a specific style of input for chat interactions, such as following natural language instructions or responding in accordance with human preferences. This stage usually involves two main steps: instruction finetuning (IFT) and preference finetuning (PreFT). I want to focus on the former. Most IFT data comes in question-answer pairs containing a user instruction, an optional context, and a given response.

For the next year or so, I believe there’s a more urgent need for Filipino IFT datasets.

A simple language modelling pipeline (as seen in models like InstructGPT, Tulu 2, etc.).

Currently, we lack quality Filipino data for post-training.

I want to focus on collecting IFT data because it can be tailored to specific domains and is more economical to run experiments with. This means that NLP researchers interested in Filipino can still continue focusing on their own domains of interest while still contributing to this larger goal of improving our Filipino data pool. Take SciRIFF for example: it contains question answering pairs for scientific literature that serves the authors’ own purpose, yet we were able to use it in Tülu 3 to build generalist language models that are capable of chat, reasoning, coding, and other skills. In addition, IFT is computationally cheaper than pretraining; laboratories with a decent grant and cloud capacity can easily finetune a 7B-parameter model. Preference data is also important, but collecting it requires more annotation effort and stronger multilingual models that actually work in Filipino (for that we need good evaluation, which I’ll discuss in the next section).

Philippine languages lack quality instruction finetuning data

As of now, Philippine languages lack quality IFT data. The best we have so far is the Aya dataset, with around 1.46k samples for Tagalog and 4.12M for Cebuano. At first glance, Cebuano looks promising with more than a million examples, but upon inspection, majority of these examples were translated from another language (possibly English) or was derived from the Cebuano Wikipedia which is mostly synthetic and unnatural.1 There are several ways to collect IFT data. We can (1) annotate our own datasets, (2) translate existing English IFT datasets into Filipino, or (3) repurpose existing Filipino datasets into a question-answering format. It’s important to note that these datasets don’t need to focus on general chat. Researchers can continue working in their domains of interest while reframing their problems as question-answering tasks.

Ideally, collecting Filipino IFT instances in the order of hundreds of thousands (100K-400K) is crucial for this work. It would be even better if these instances were evenly distributed across our major languages (e.g., Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilokano, Hiligaynon). Once we have this dataset, it will then be easier for us, the Filipino language community, to train our own generalist LLMs. In addition, it also makes it easier for other organizations to incorporate our dataset into their own data mixing pipelines thereby increasing the representation of Filipino to these larger-scale LM projects. Collecting 100k instances seems daunting, but I already have some ideas in mind.

Build reliable benchmarks for Filipino

Key Insight: We need to systematically answer the question: “Does this LLM work on Filipino?” Although we already have several datasets that examine various aspects of the Filipino language, we need to curate which of these are relevant for LLM evaluation then build an evaluation suite.

Even before we start training language models, it is important to measure how current state-of-the-art LLMs perform on Filipino. Most of the evidence I see is anecdotal: someone will post a single ChatGPT screenshot in Filipino and claim that the model already understands the language. However, it is easy to see how this performance can degrade during extended conversations, such as misunderstanding idioms and expressions or lacking cultural knowledge. We need a systematic approach to evaluating these models.

We have several promising benchmarks at hand. For example, KALAHI tests an LLM’s ability to discern the correct response in culturally-specific situations that Filipinos face in their day-to-day lives. NewsPH NLI and EMoTES-3k are also relevant as they reflect some of the potential questions that one might ask an LLM. I believe that through the years, we have developed several datasets that tests different facets of the Filipino language. We need to scour and curate them to filter those that are relevant for Filipino use-cases. Several frameworks allow us to do this, such as Eleuther AI’s harness and HuggingFace’s lighteval, which enable us to seamlessly evaluate multiple LMs at scale.

Creating a language-specific benchmark is useful because it serves not just the academic community for that language but also the industry at large. It allows us to say “this LLM works on these specific Filipino tasks but fails at others” in academia and helps advise industry practitioners on which LLMs work on their particular use cases. This also opens up several potential avenues to advocate particular research directions for Filipino— focusing on language X, building a language-specific LLM, etc.— because we have metrics to hold ourselves to (while acknowledging Goodhart’s Law). Basically, we just need something instead of nothing, and that something is a huge step forward.

Participate in grassroots research efforts

Key Insight: There are several large-scale grassroots research efforts happening as we speak. We need a lot of Filipino representation in these initiatives. Here’s an opportunity: join our Grassroots Science effort that we will launch next year!

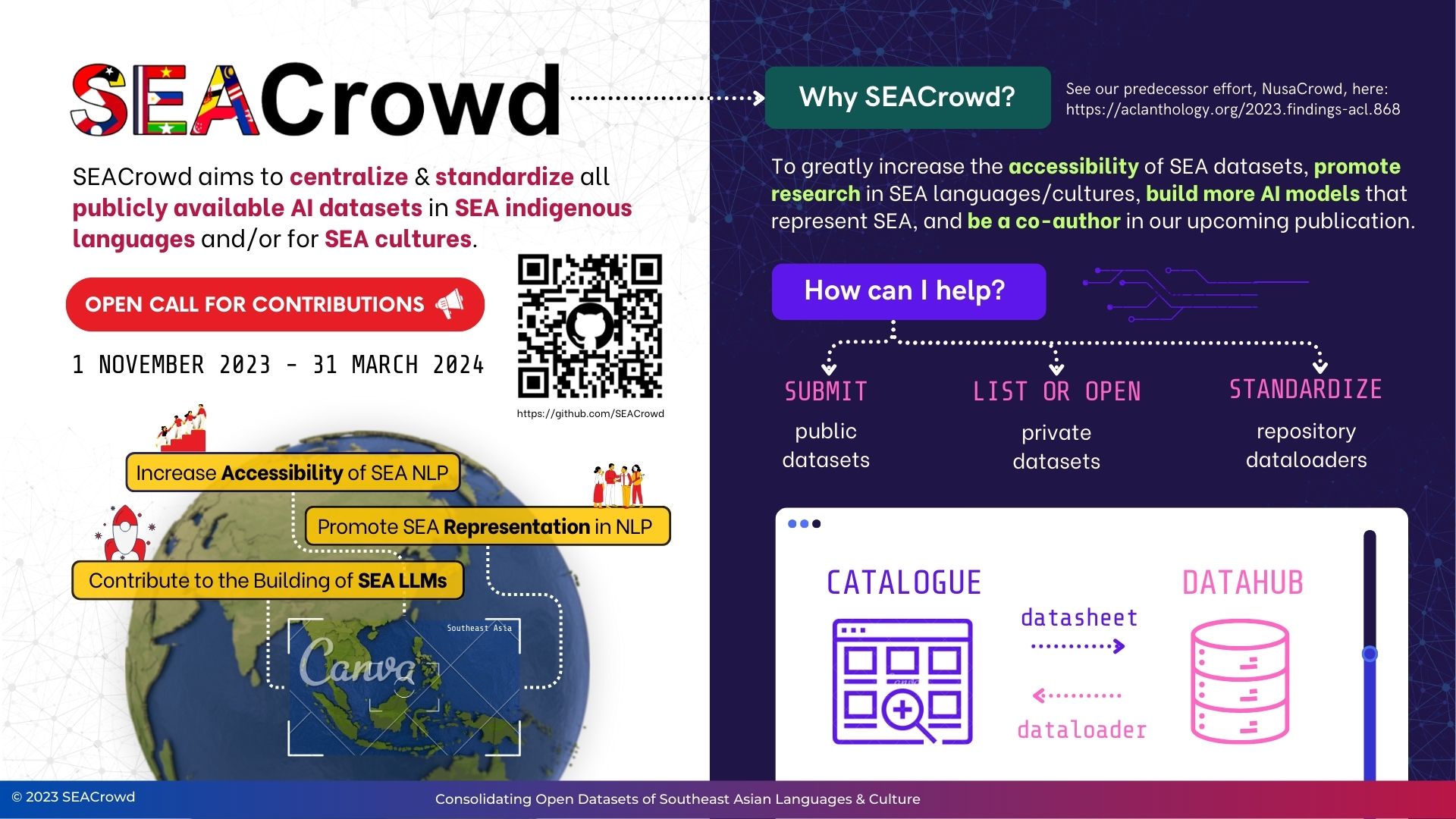

For the past few years, I’ve witnessed several grassroots NLP efforts that led to significant breakthroughs in the multilingual world. SEACrowd is one example. They were able to rally a community of researchers from Southeast Asia (SEA) and build a data hub for all SEA datasets, which is very much needed today. Other examples include Cohere for AI’s Aya and HuggingFace’s Data is Better Together projects. Right now, it’s nice to see familiar Filipino faces participating in these communities, but it would be nice if we can increase our involvement in these larger grassroots projects.

I strongly believe that we can achieve true impact in multilingual LLM research via a participatory approach. This means actively collaborating with researchers and immersing ourselves in grassroots efforts focused on data annotation, data curation, and model testing. This approach stands in constrast to the sweatshop model, where Filipino annotators, though recruited, are excluded from meaningful participation since they merely follow annotation guidelines set by their employers without input into the process.

Here’s a call to action: we’re launching a year-long Grassroots effort to collect preference data for LLM post-training in different languages. It would be awesome to see fresh Filipino faces helping us out— so join us! This is important because human preferences, even in English, is still tricky due to its subjectivity and diversity. Things that may be harmless to some cultures might be harmful for us. I believe it is important for us, the Filipino research community, to have a say on how the next-generation of multilingual LLMs will be trained.

Final thoughts: are we truly ‘low-resource’?

“Low-resource” is a term the NLP research community use to describe languages that lack sufficient resources for building language technologies. Many indigenous and endangered languages fall into this category due to their limited number of speakers and dedicated NLP researchers. Tagalog occupies an interesting middle ground: while we have a large speaker population and presumably extensive written content, there remains a scarcity of readily available datasets for downstream NLP tasks.

One of my favorite papers this year, The Zeno’s Paradox of Low-Resource Languages, helped clarify these definitions by examining how we define “low-resource” across different axes: Artifacts, Resources, Socio-Political factors, and Agency. Although Tagalog has millions of speakers (↑ Resources), it still lacks high-quality data for several core NLP and language modelling tasks (↓ Artifacts), and there remains significant room for growth in our participatin in developing these language technologies (· Agency). I appreciate this framework because it provides multiple dimensions for measuring a language’s low-resource status, eliminating the need to debate or bikeshed new definitions.

I maintain that Philippine languages remain low-resource across several dimensions. Even Tagalog, our majority language, still lacks the necessary tools and datasets to produce robust NLP pipelines. I believe the three research directions I described above can both increase the number of artifacts available for building language technologies and enhance our agency as a research community. I admit that I haven’t done enough for Filipino NLP this year2 and this blog post serves not just as a research statement but also a commitment to improve my involvement in this language. I have some ideas (the ideas in this blog post are just a small part of it), so if you want to help out, feel free to reach out!

-

The Cebuano Wikipedia is the second-largest Wikipedia in terms of number of articles. Although this appears impressive, its size is due to an article-generating bot called Lsjbot rather than a dedicated group of Wikipedia volunteers. Unfortunately, the articles in Cebuano Wikipedia are unnatural and do not reflect how the language is actually used by native speakers. ↩

-

This year we published SEACrowd, Universal NER, and the largest Tagalog UD Treebank, but most of these efforts started back in 2023. ↩