Guest lecture @ UNC Charlotte: Labeling with LLMs

A few weeks ago, I held a guest lecture in the DSBA 6188: Text Mining and Information Retrieval Class at UNC Charlotte on using large language models (LLMs) for annotation. It was fun because I could expand my previous blog posts on LLM annotation into a full-fledged lecture.

This blog post is my (abridged) lecture in written format. You can find the slides in this link. Finally, thanks to Ryan Wesslen and Chang Hsin Lee for inviting me!

Case in point: automated fact checking

One of the major problems of the 21st century is disinformation. You’ll see it everywhere, from Facebook posts or X tweets to fake news websites! Combating disinformation is labor-intensive. Politifact, a fact-checking website, relies on volunteer journalists to scour the internet and manually label each source.

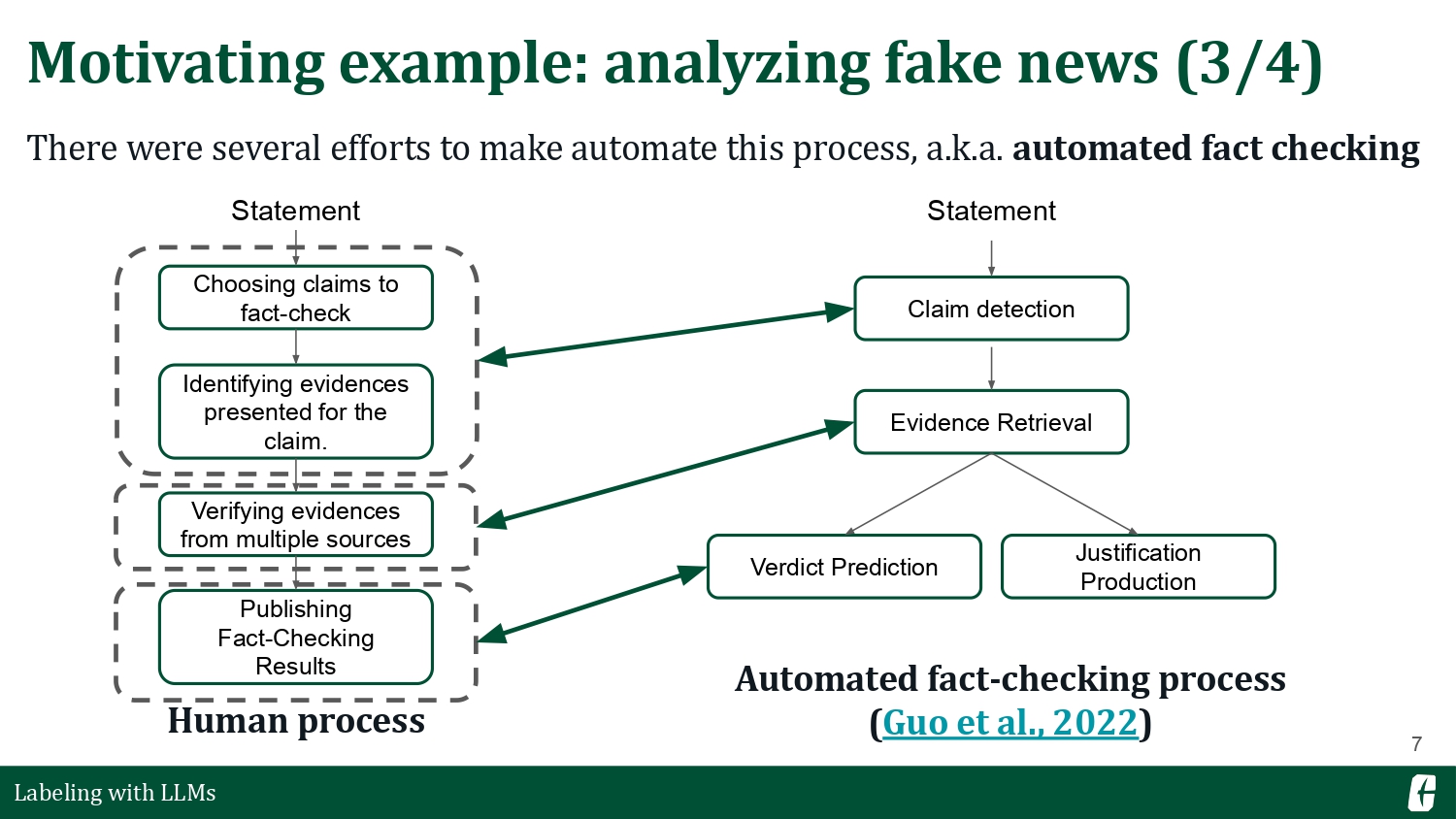

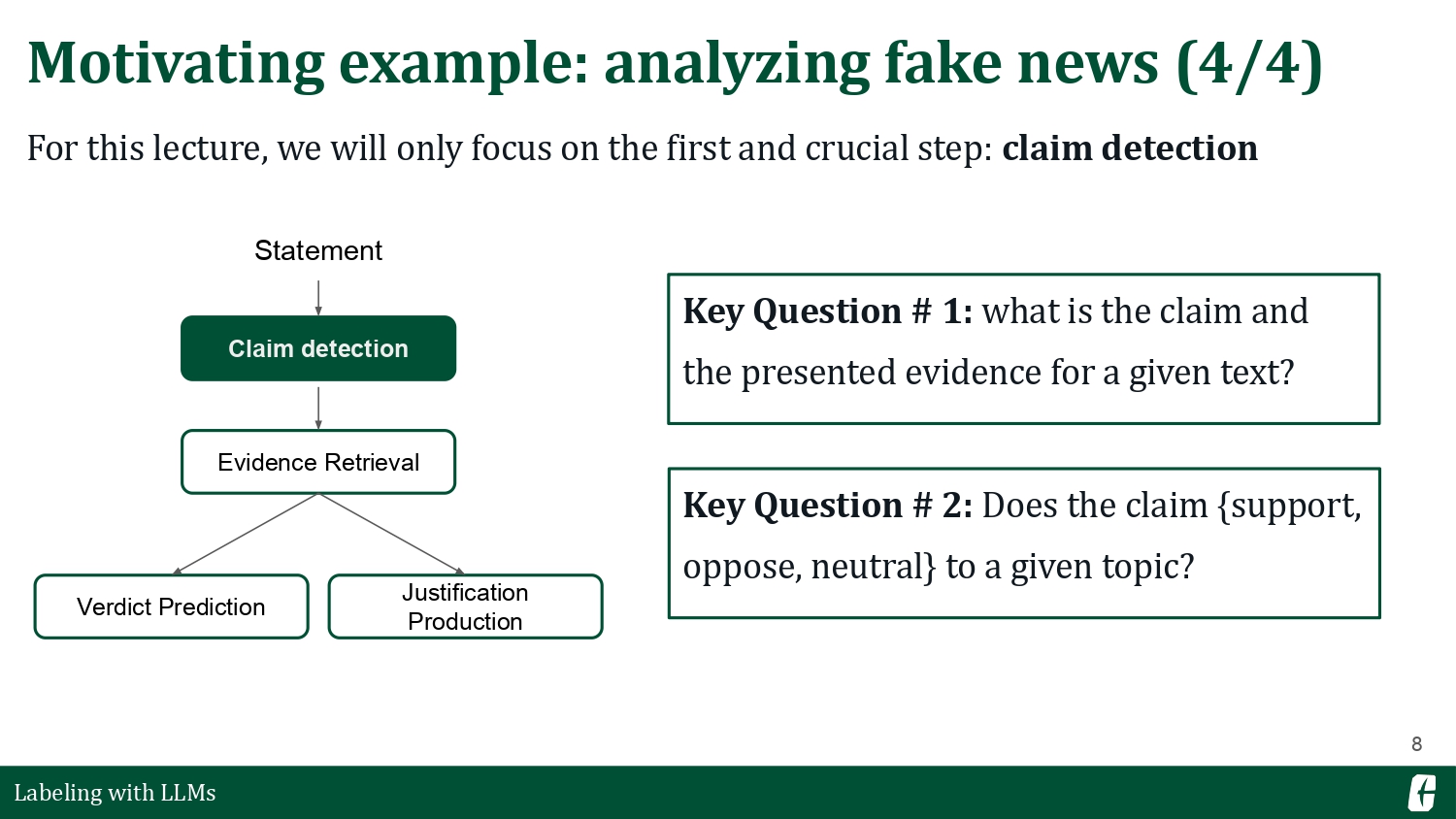

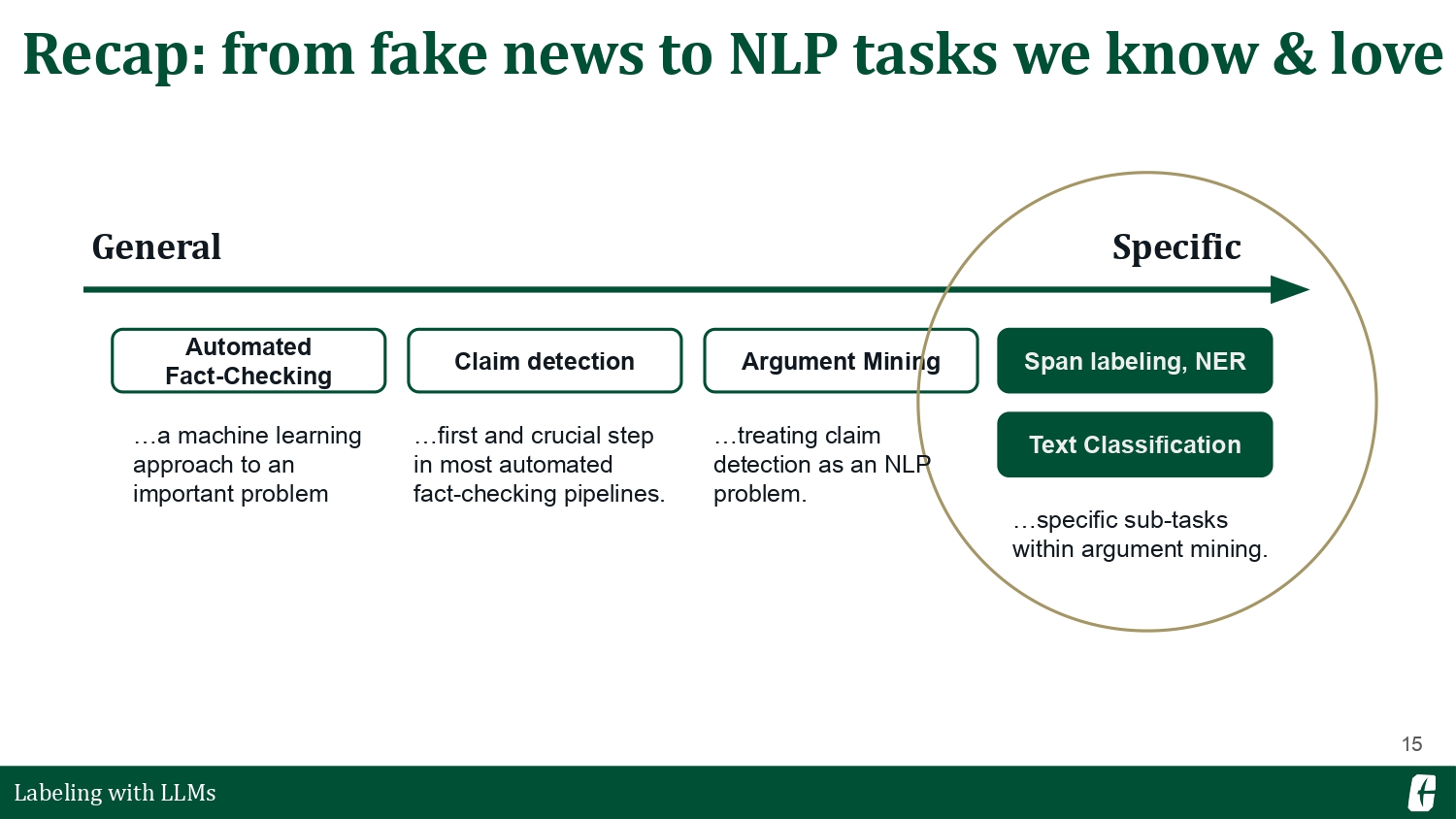

There are several efforts to automate the fact-checking process. A common approach is to treat it as an NLP pipeline composed of different tasks (Guo et al., 2022). Today, we will only focus on claim detection, the first step in an automated fact-checking pipeline.

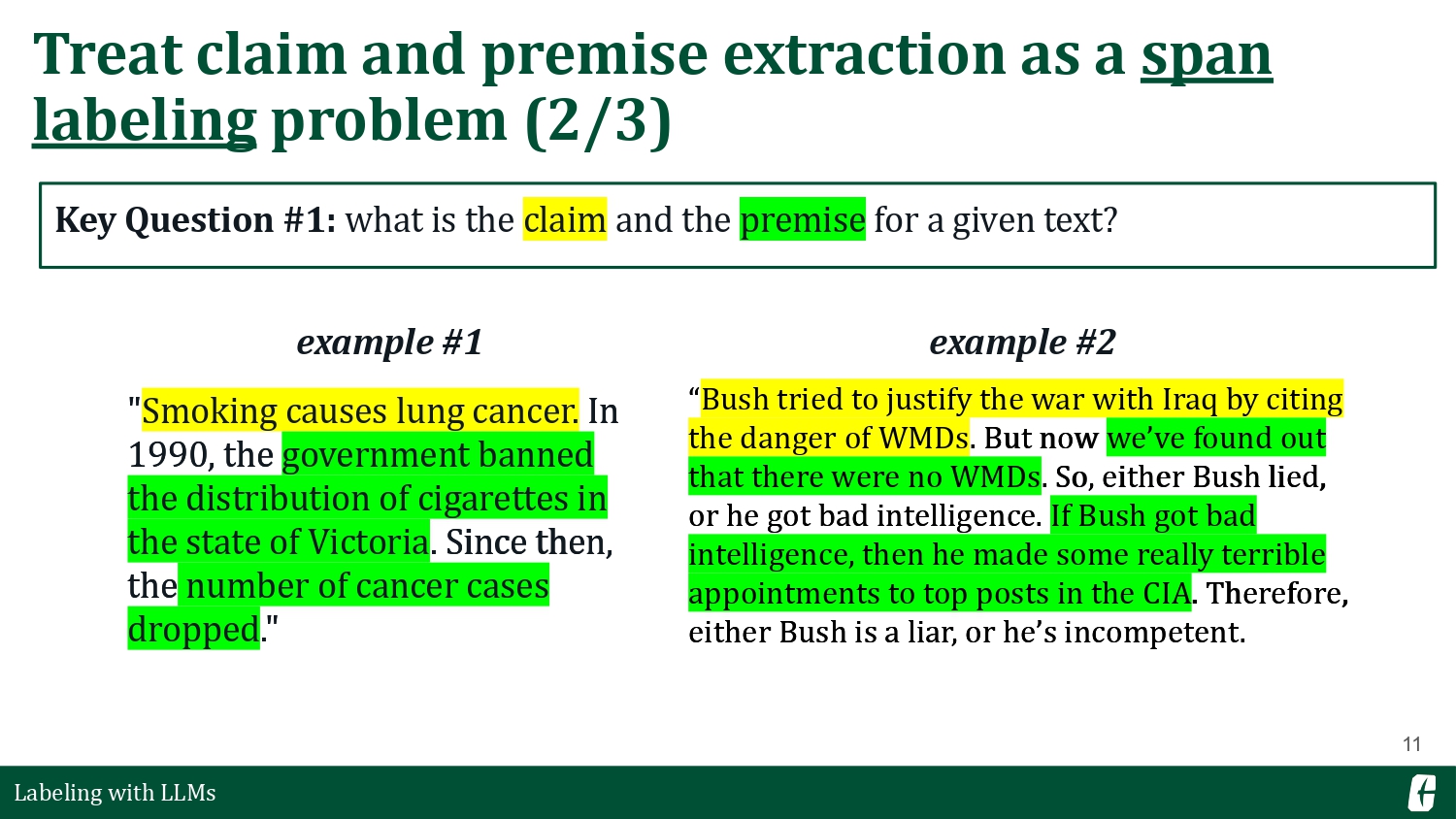

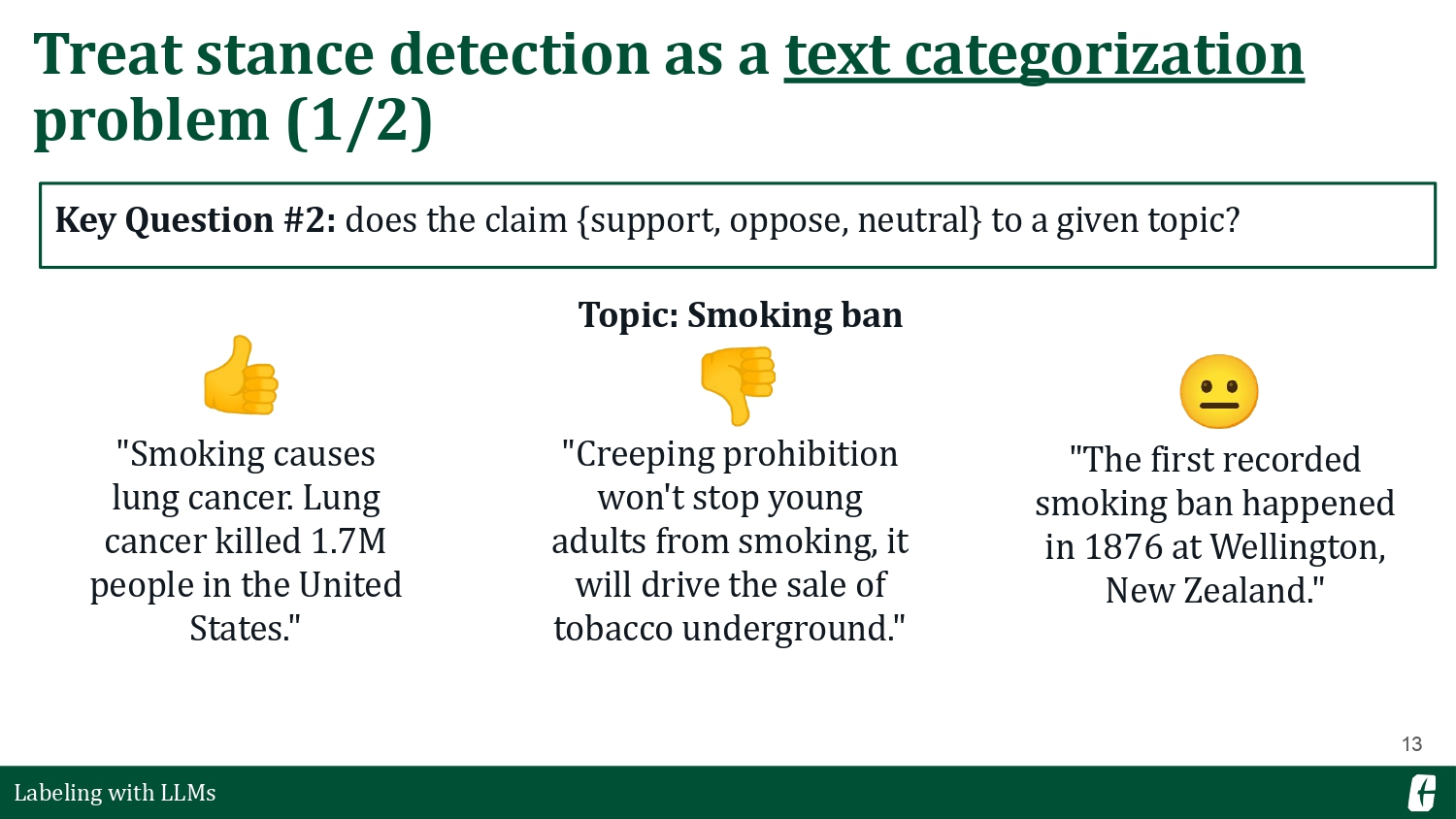

Detecting claims is usually a dual problem: you’d also want to find the premises that support it. Together, the claim and its premises make up an argument. Applying NLP to this domain is often called argument mining. For this talk, I want to introduce two argument mining sub-tasks: (1) first, we want to highlight the claim and premise given a text (claim & premise extraction), and then, (2) we want to determine if a text supports, opposes, or is neutral to a certain topic (stance detection).

So, our general approach is to reframe these two sub-tasks as NLP tasks. First, we treat claim & premise extraction as a span labeling problem. We can use spaCy’s SpanCategorizer to obtain spans or arbitrary slices of text. Then, we treat stance detection as a text categorization problem. Similarly, we can use spaCy’s TextCategorizer to classify a text among our three stances (support, oppose, neutral).

Notice how we’ve decomposed this general problem of disinformation into tractable NLP tasks. And it is an important muscle to train. In computer science, we often learn about the divide and conquer algorithm, and this is a good application of that approach to a more fuzzy and, admittedly, complex problem.

As we already know, training NLP models such as a span or text categorizer requires a lot of data. I want to talk about different methods of collecting this dataset and emphasize how LLMs can fit into this workflow.

Annotating argument mining data with LLMs

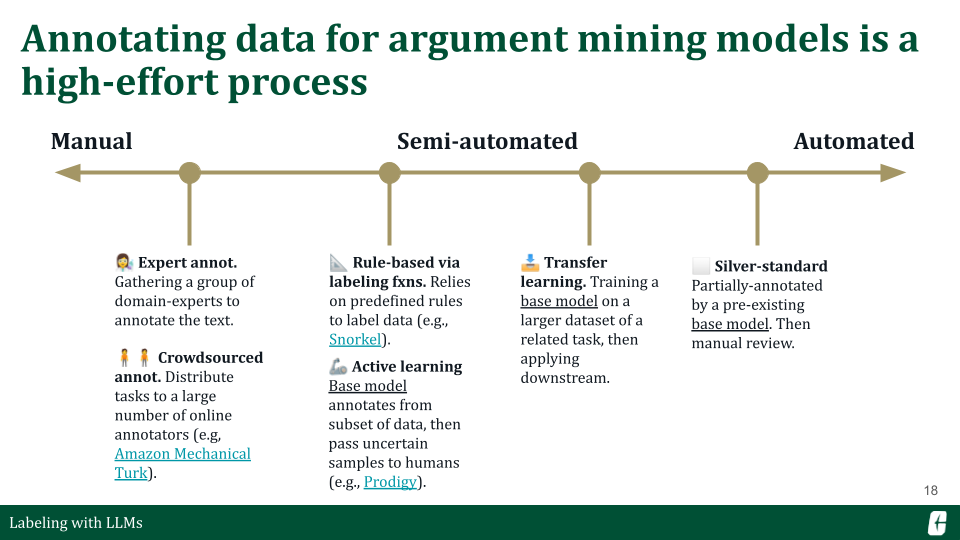

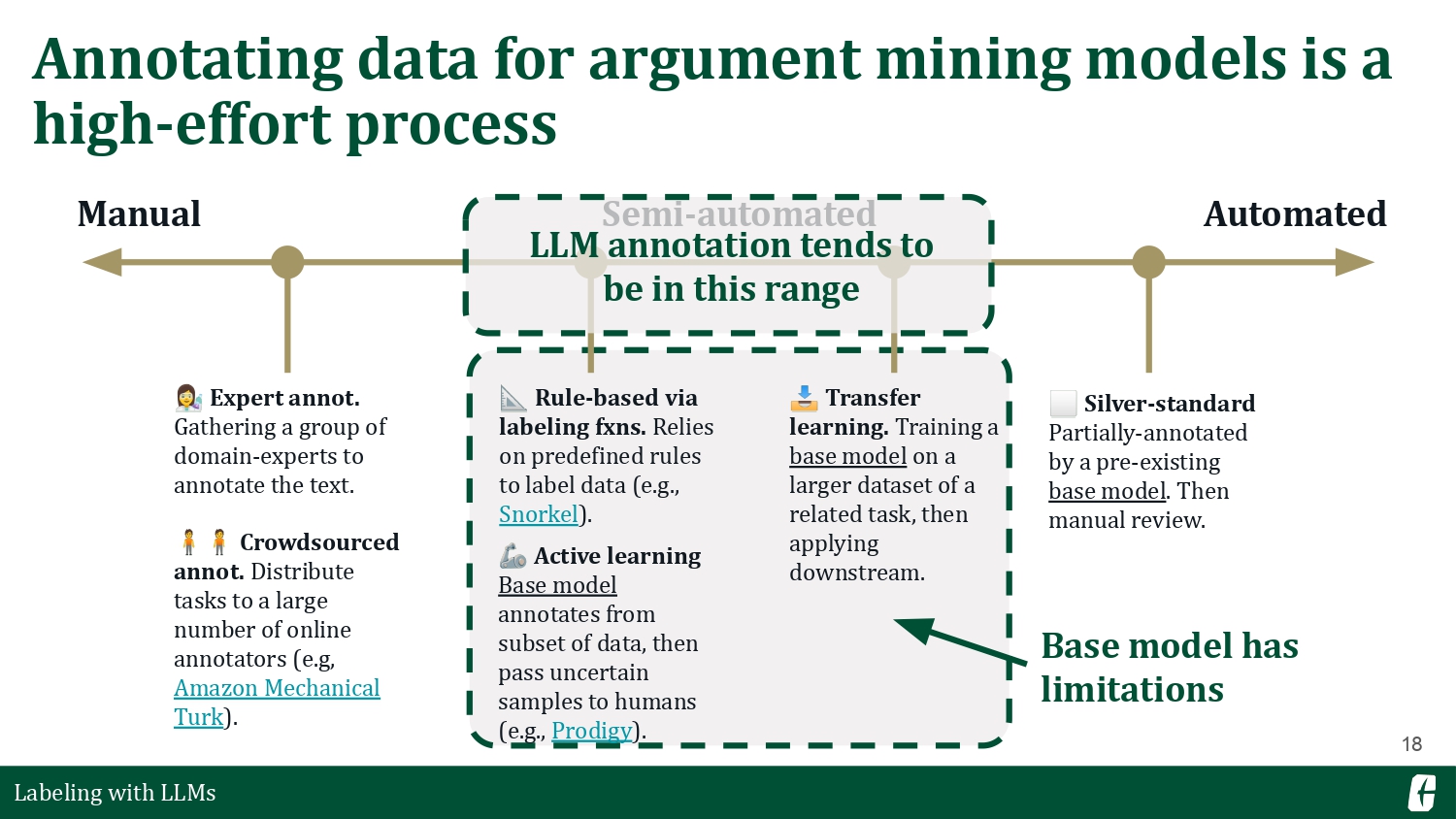

Before we get into LLMs, I want to talk about “traditional” ways of annotating data. On the left end, we have manual processes involving much human effort and curation. And then, on the right, we have more automated methods that rely heavily on a reference or base model. LLMs, as advanced as they are, still fall in between. They’re not fully manual but also not fully automated because writing a prompt still requires tuning and domain expertise.

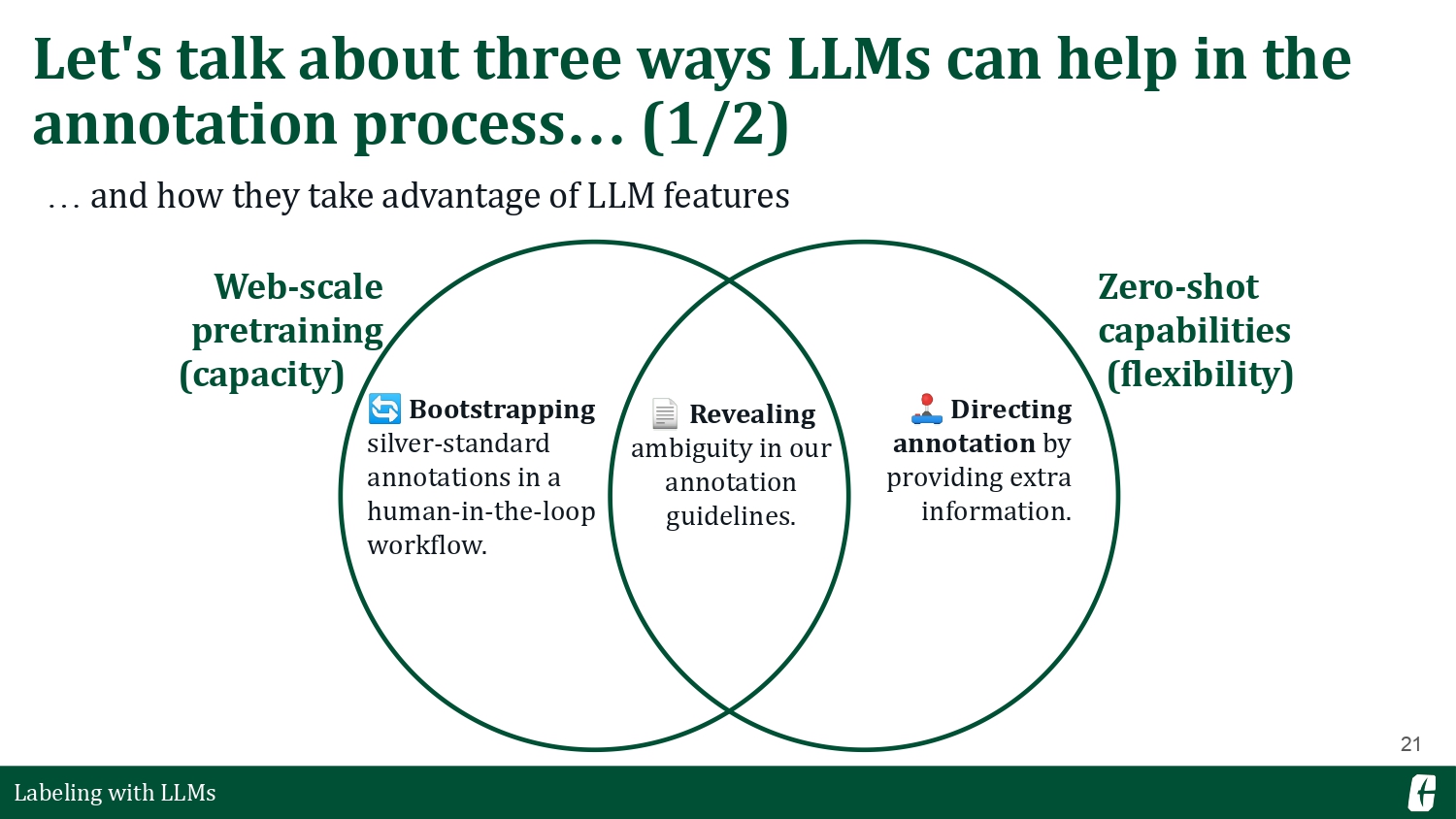

But why are we still interested in LLMs? It’s because LLMs provide something that most semi-automated methods can’t: a model pretrained on web-scale data, and a highly flexible zero-shot capability. Let me put this in a Venn diagram— and for each space in this diagram, I’ll talk about how LLMs can specifically help in our annotation workflows.

Bootstrapping in a human-in-the-loop workflow

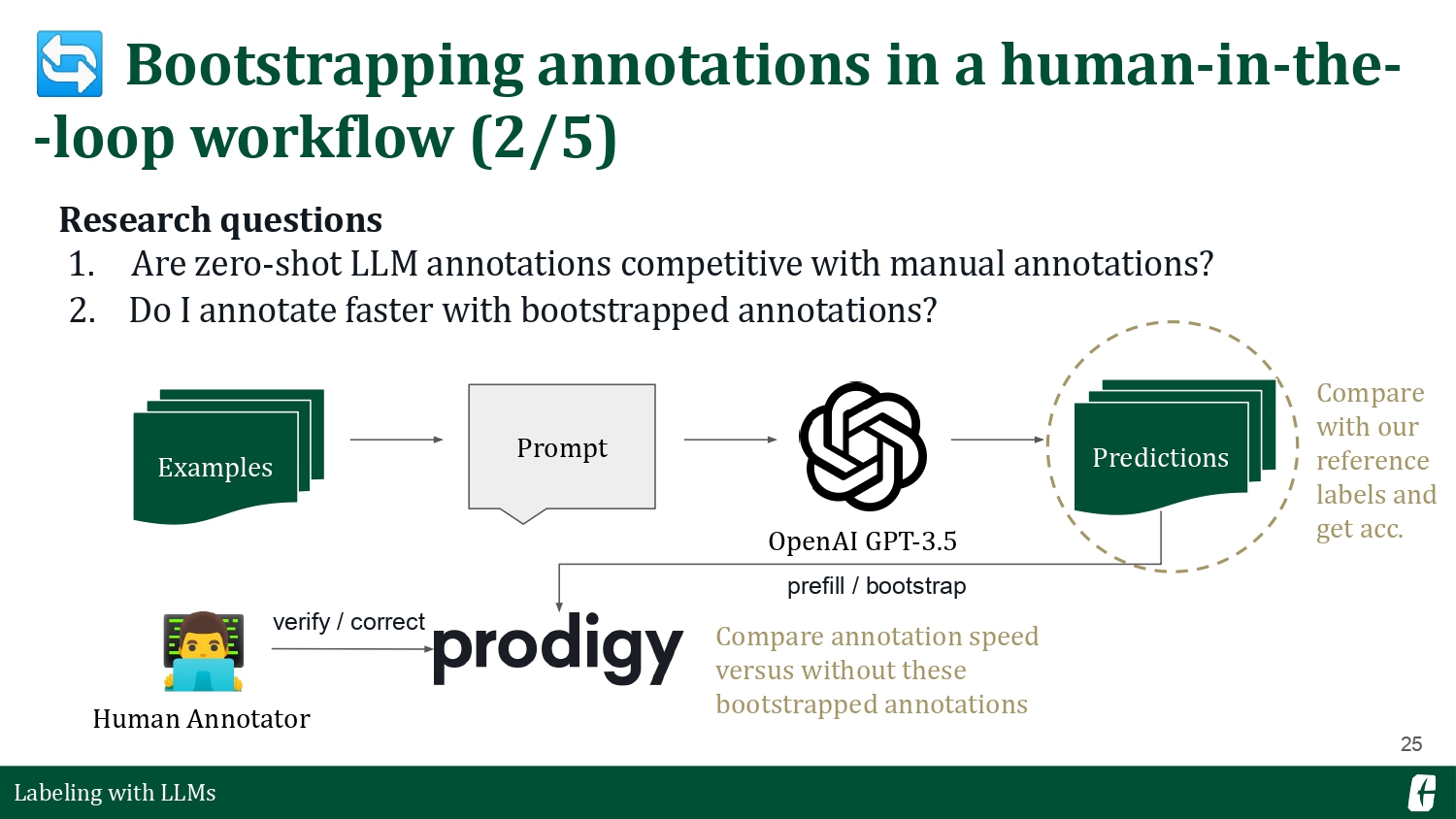

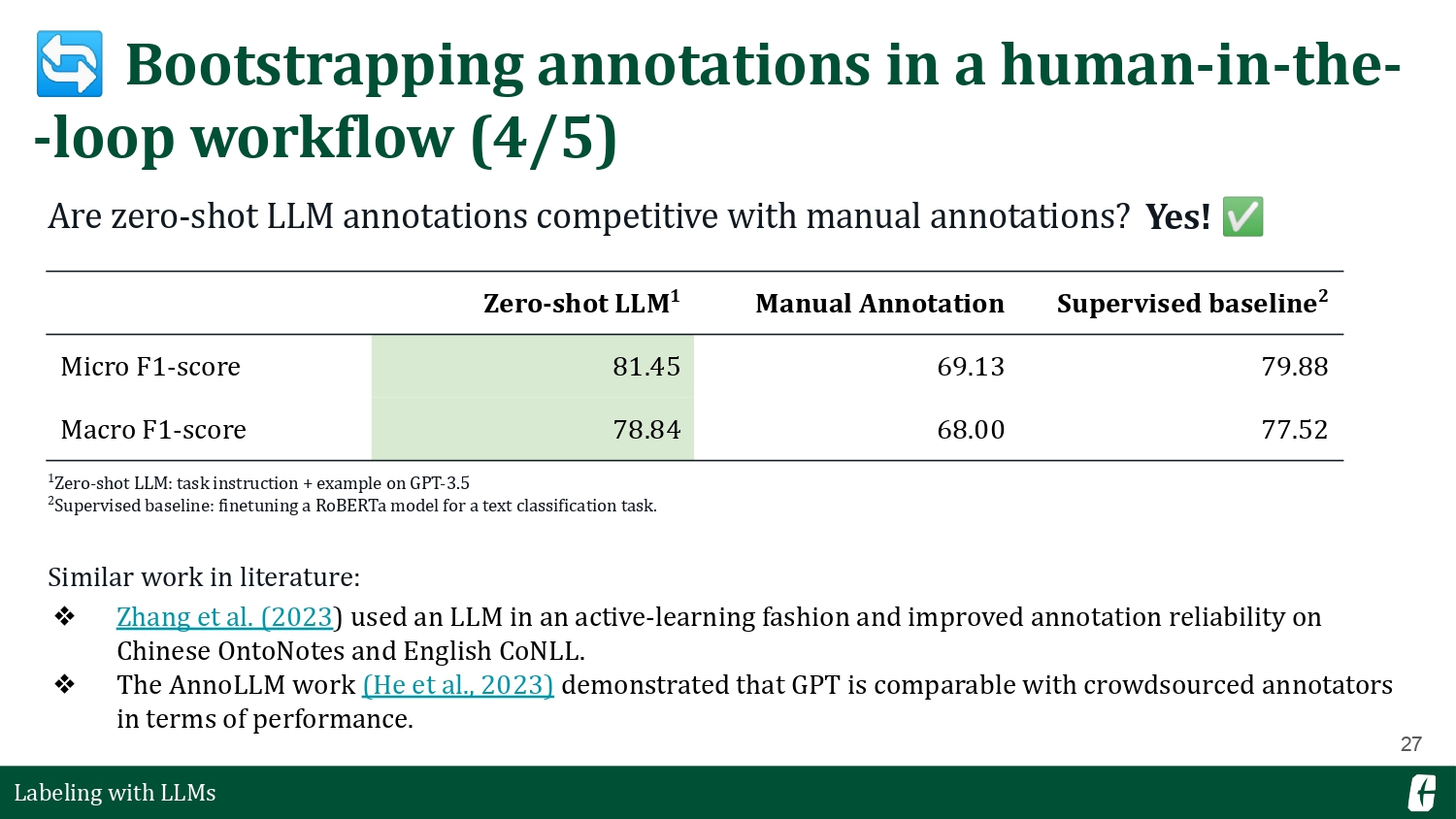

One of the most straightforward applications of large language models is bootstrapping labeled data. Here, an LLM is a drop-in replacement for a base model that you’d usually train. LLMs differ because they were pretrained on web-scale data, giving it enough capacity even for your domain-specific task. So, how good is an LLM annotator?

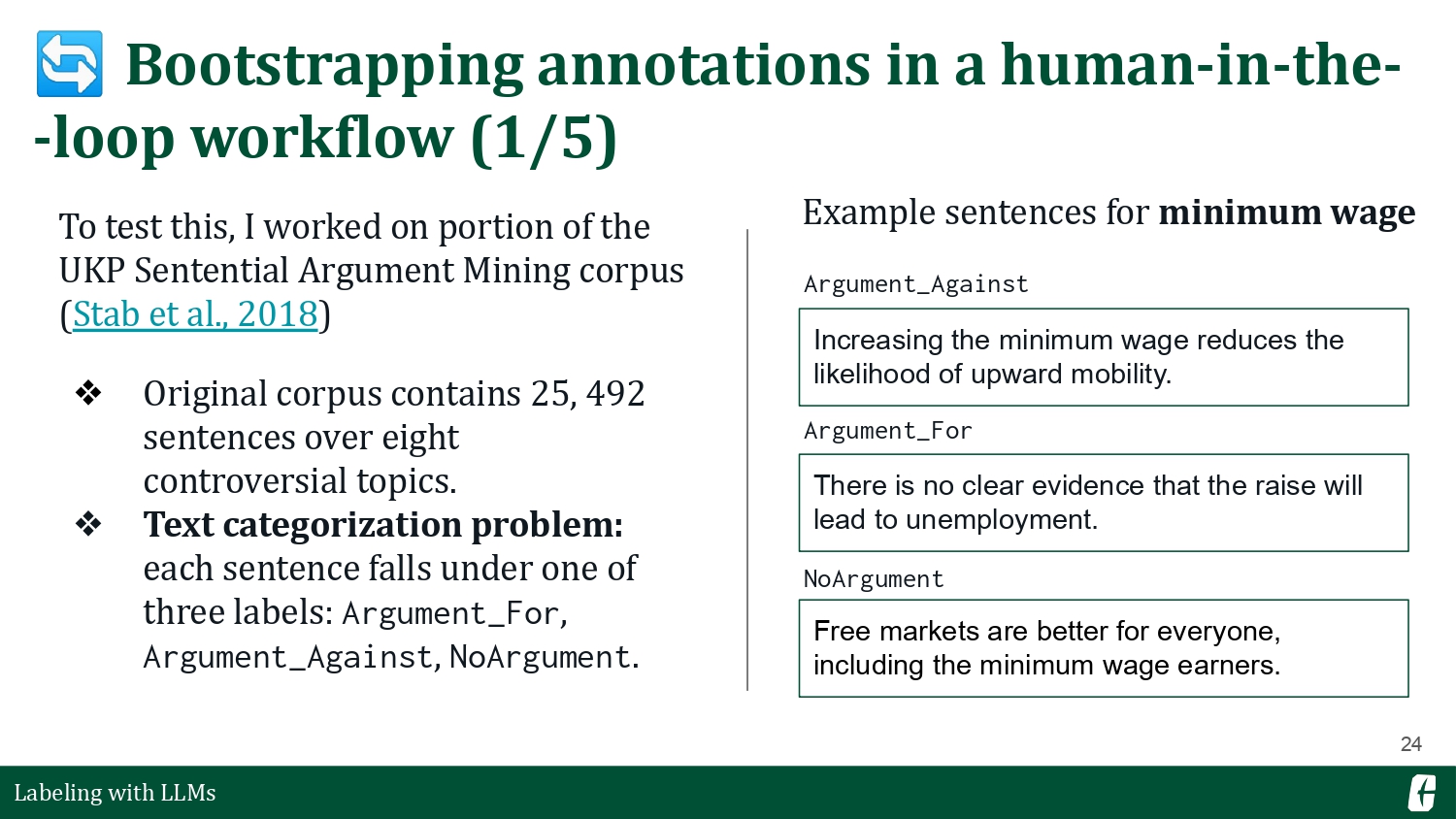

To test this question, I worked on a portion of the UKP Sentential Argument Mining corpus (Stab et al., 2018). It contains several statements across various topics, and the task is to determine whether the statement supports, opposes, or is neutral to the topic— a text categorization problem.

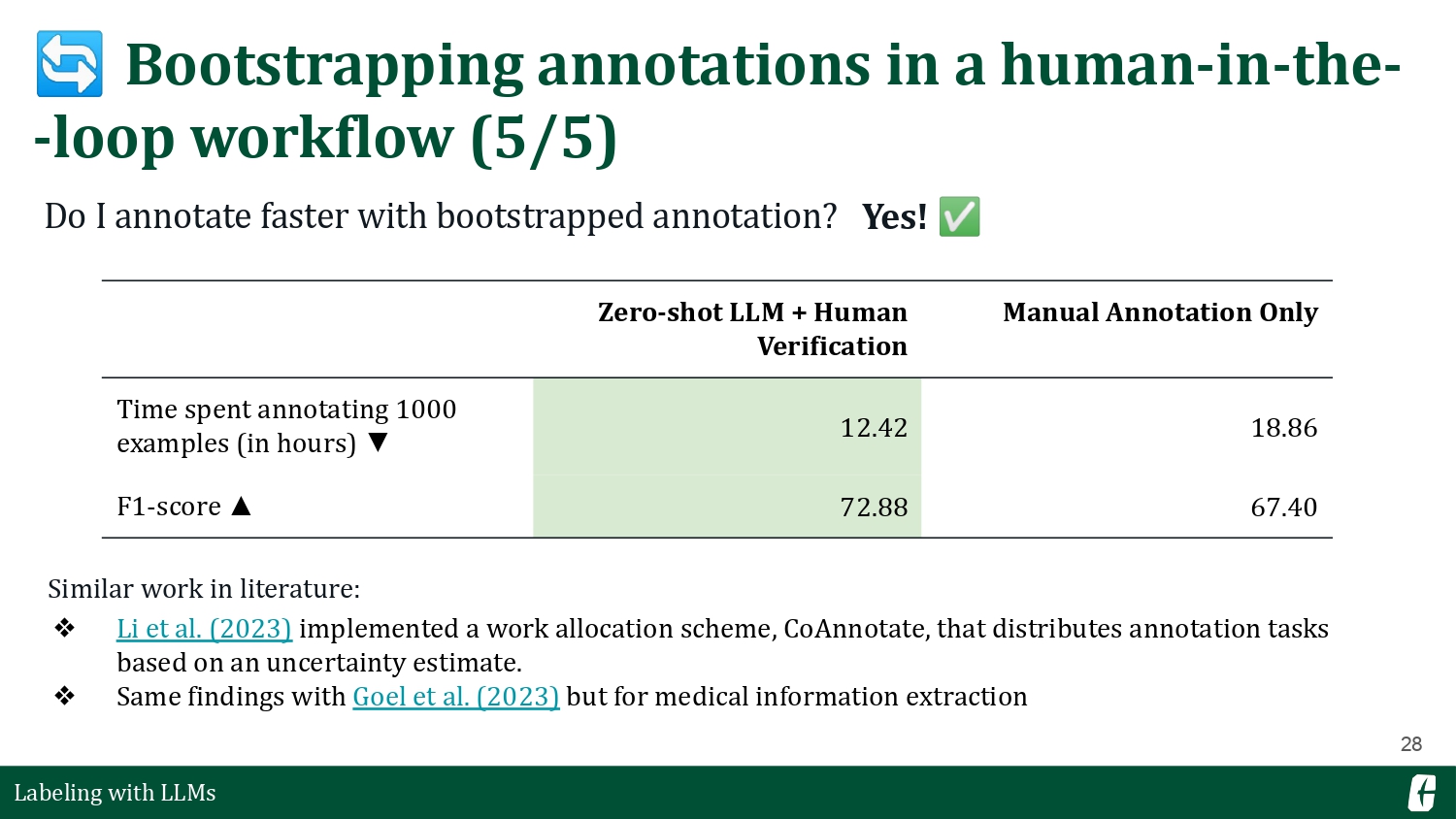

The process was simple: I included each statement in a prompt and asked GPT-3.5 what the stance was. You can read more about my process in this blog post. My findings show that LLMs, when prompted in a zero-shot manner, are competitive on a baseline that I trained on the original labels. In addition, I also found myself annotating faster (and more correctly) when correcting LLM annotations compared to annotating from scratch. The latter finding is important because correcting annotations induces less cognitive load and human effort (Li et al., 2023, Zhang et al., 2023).

So, if LLMs can already provide competitive annotations, is our problem solved? We don’t have to annotate anymore? Remember, the reason why we collect these annotations is so that we can train a supervised model that can reliably approximate the task we’re interested in. The operating word here is reliable. There’s a huge variance in LLM performance, and one way to thin out that curve is to insert it in a human-in-the-loop workflow (Dai et al., 2023; Boubdir et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023).

Directing annotations by providing extra info in the UI

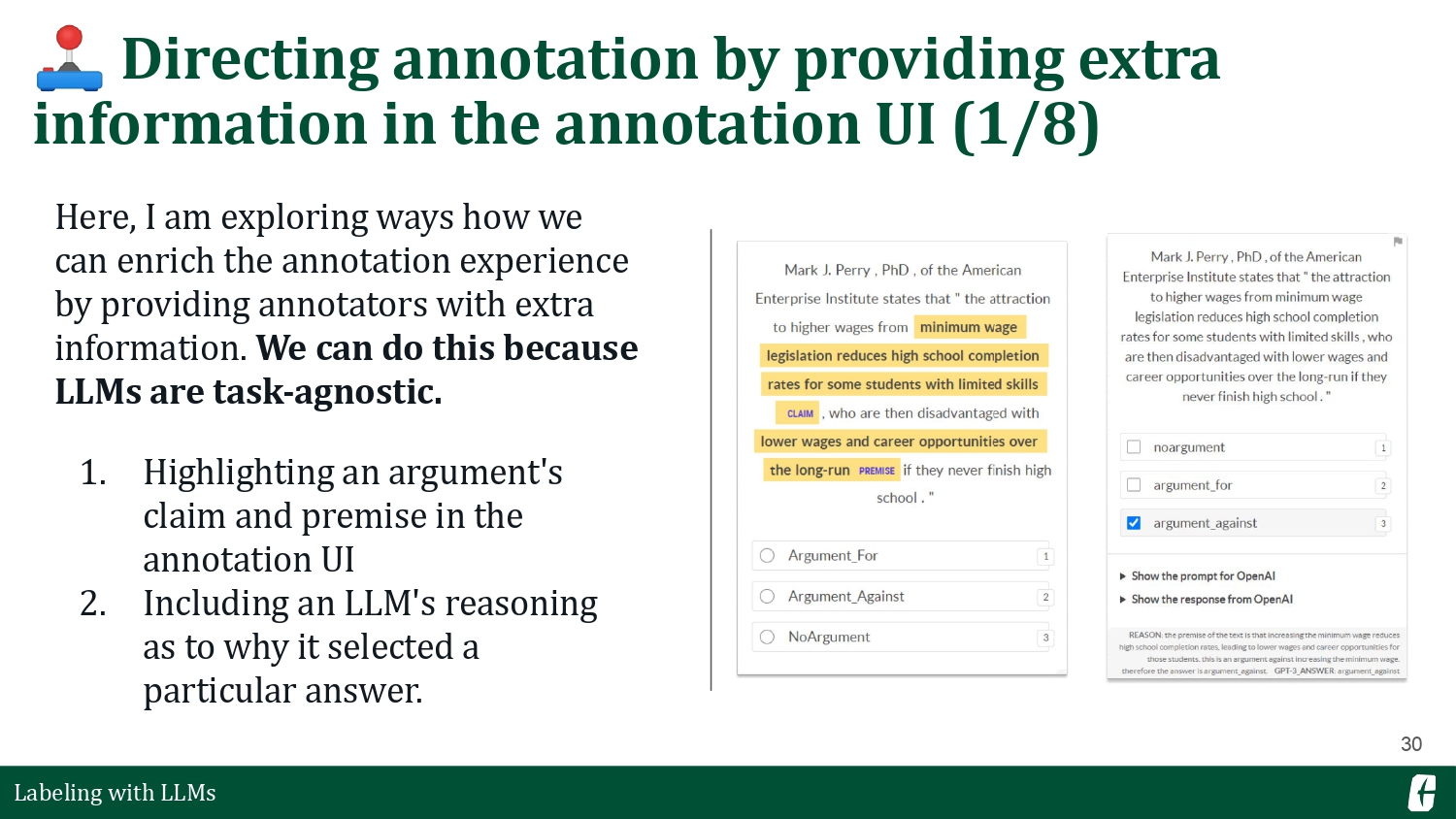

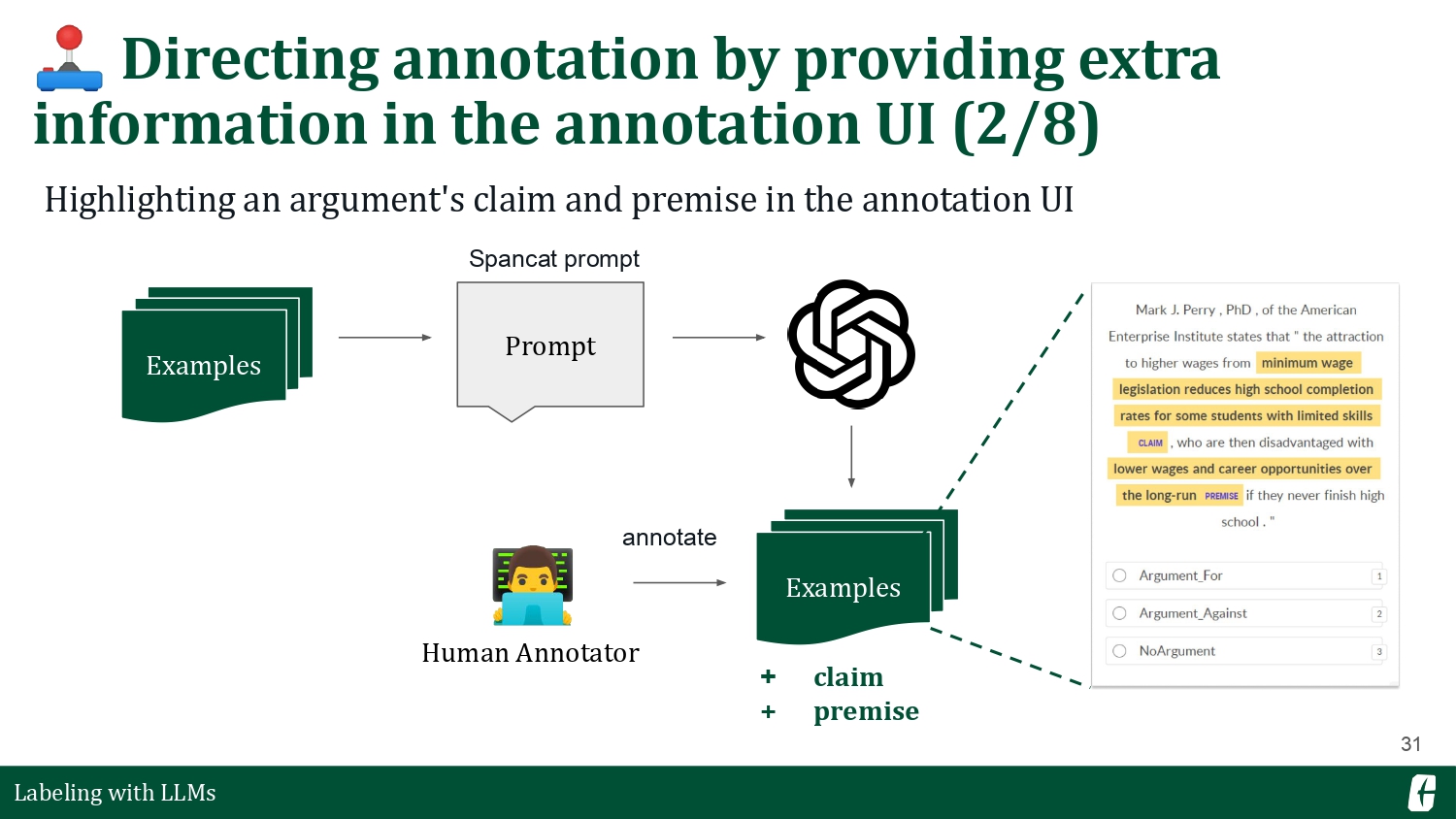

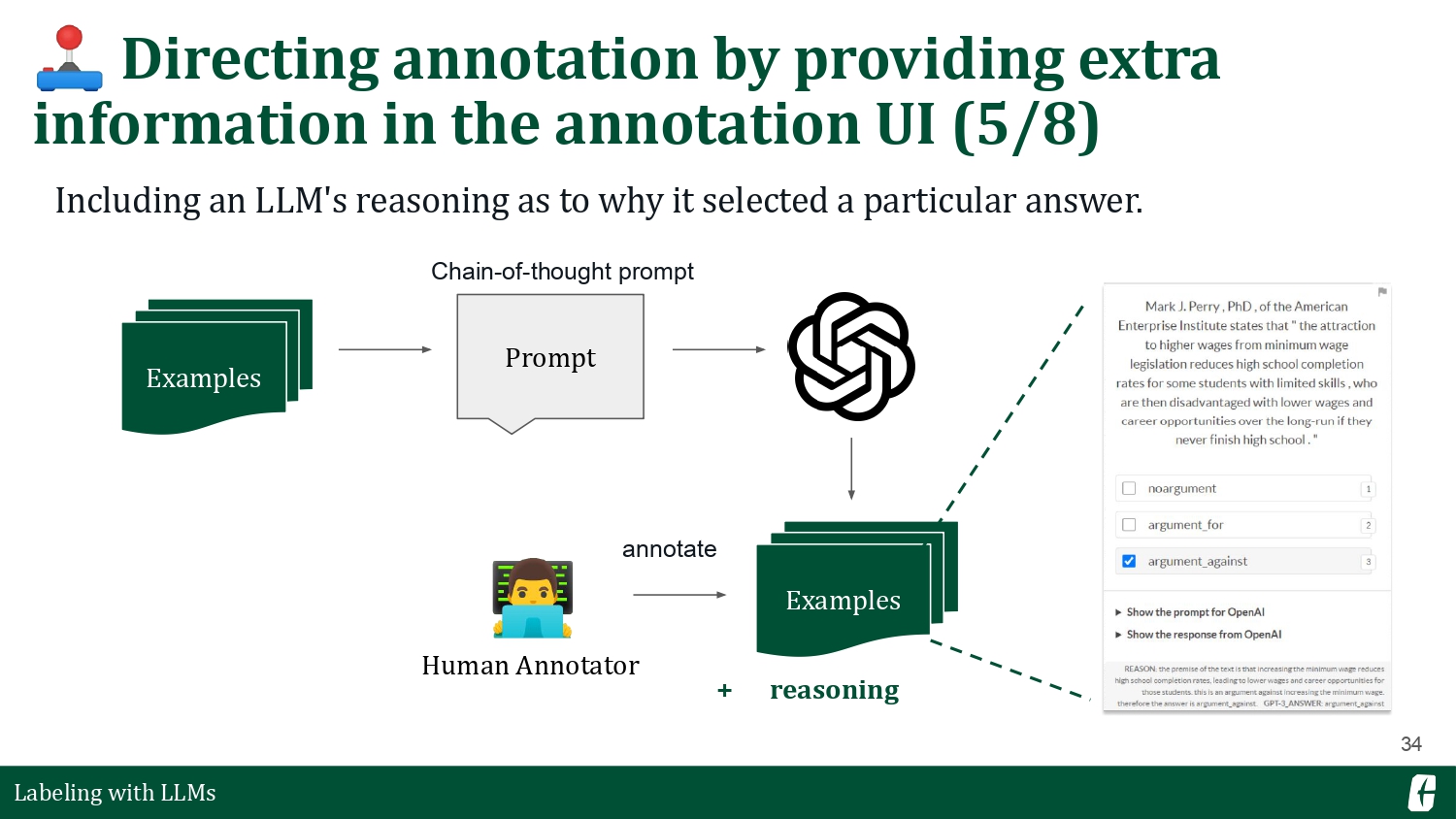

Another way we can use LLMs for annotation is by taking advantage of their flexibility. LLMs have zero-shot capabilities, i.e., we can always frame structured prediction tasks such as text categorization or named entity recognition as a question-answering problem. Back then, you’d need to train separate supervised models to achieve multi-task skills. I want to use an LLM’s flexibility to enhance the annotation experience.

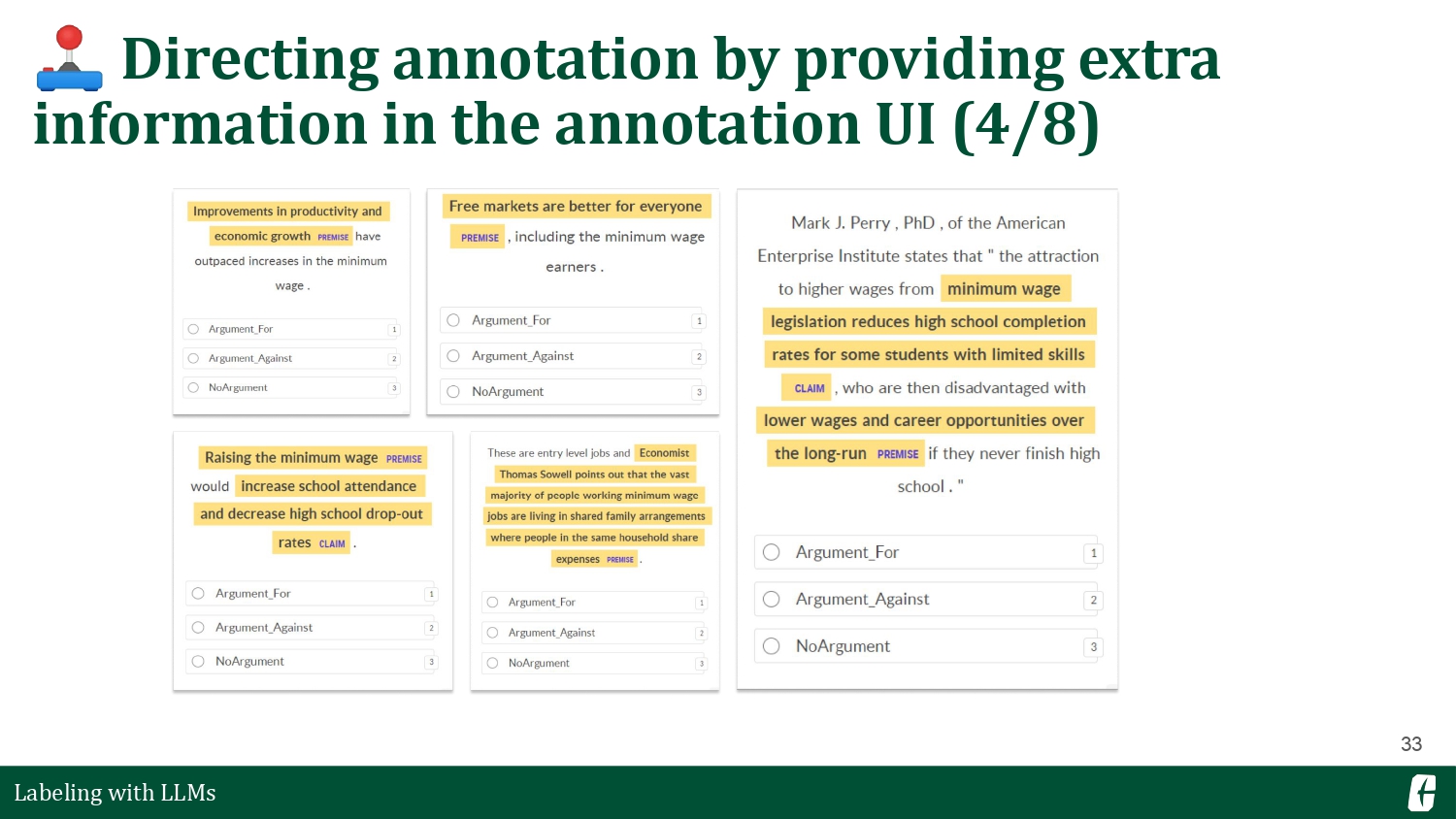

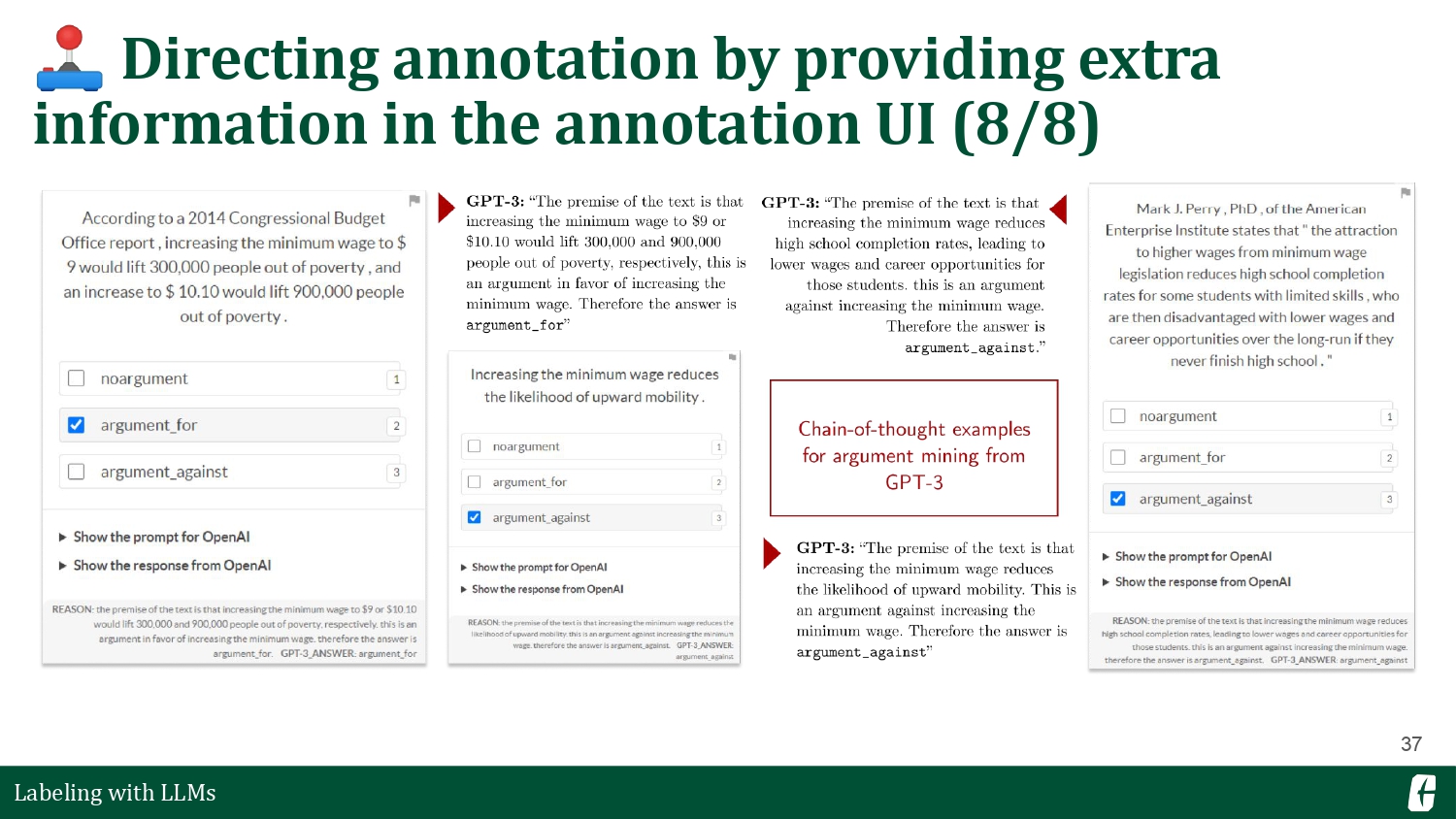

This time, I want to introduce two workflows. The first one is still a text categorization problem, but I want to ask an LLM to pre-highlight the claims and premises so I can reference them during annotation. For the second one, I want to ask the LLM to do the reasoning for me. I’ll let it identify the claims and premises, then pre-annotate an answer, and then give me a reason for choosing that answer. This exercise aims to explore creative ways we can harness LLMs.

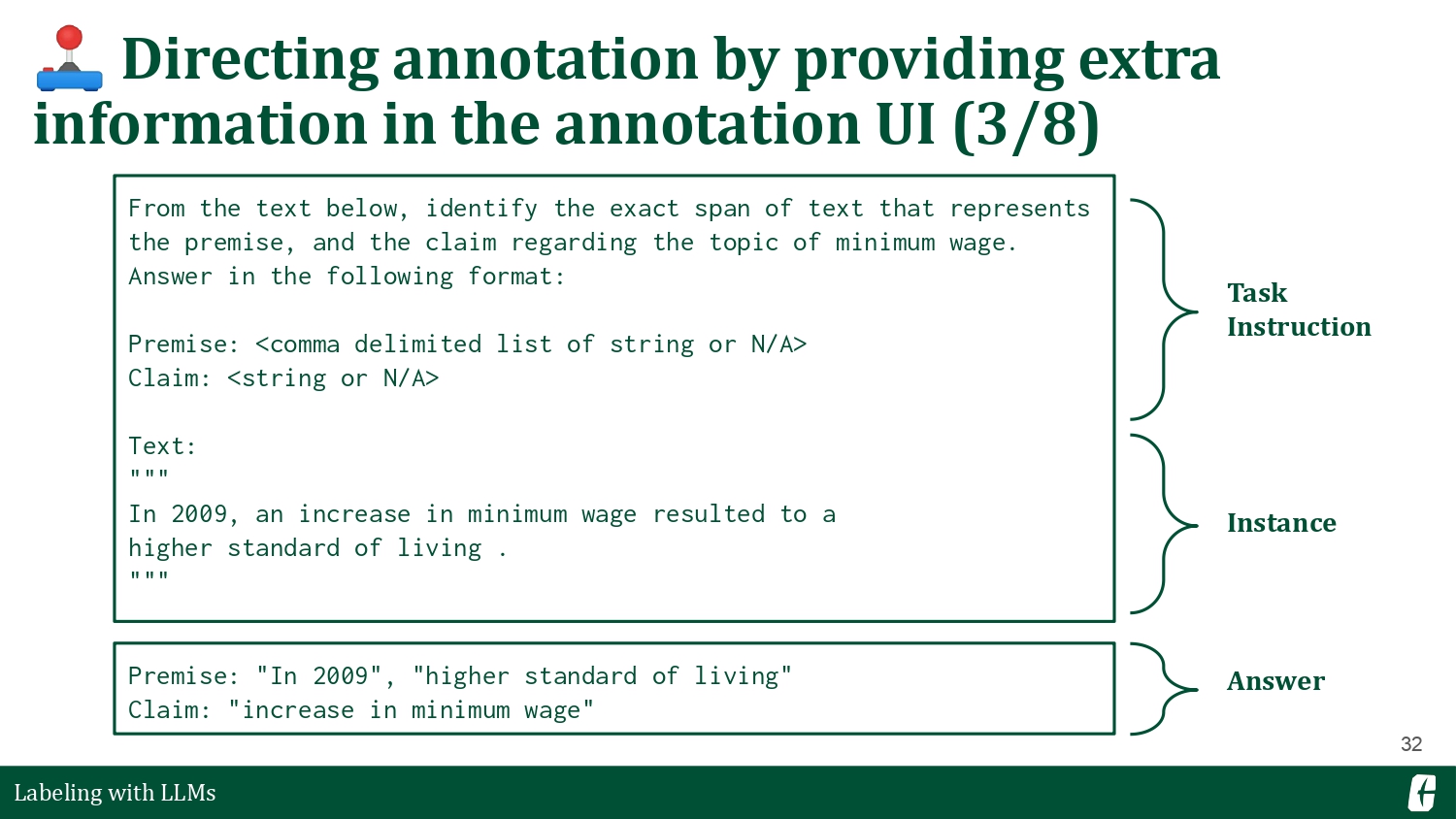

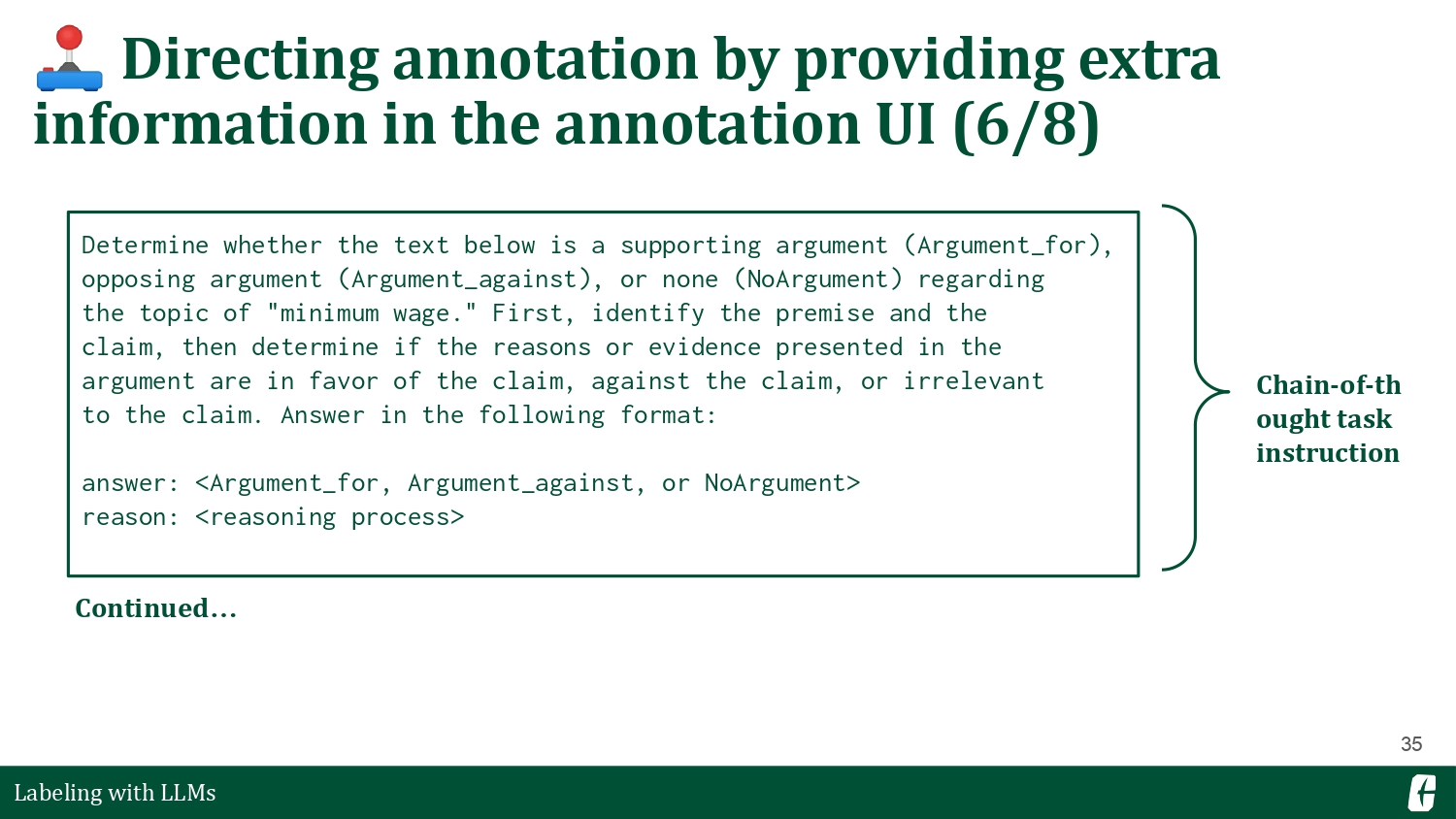

The process is similar to the first section, but I prompt for auxiliary information instead of prompting for the direct labels. LLMs make this possible because we can formulate each task as a question-answer pair. You’ll find examples of my prompt in the slides below. The prompt on the left is a straightforward span labeling prompt, where we ask the LLM to provide the exact spans from a text. On the other hand, the prompt on the right is a chain-of-thought prompt (Wei et al., 2023). Here, we induce an LLM to perform a series of reasoning tasks to arrive at a final answer.

The good thing about Prodigy is that you can easily incorporate this extra information in your annotation UI. On the bottom left, you’ll see that it highlights the claims and premises for each statement, allowing you to focus on the relevant details when labeling. On the bottom right, you’ll find that the UI metadata now contains the prompt’s reasoning steps.

There are many creative ways to improve annotation efficiency (and quality) using LLMs. One of my favorite papers from EMNLP was CoAnnotating (Li et al., 2023), which uses an uncertainty metric to allocate annotation tasks between humans and a chat model such as ChatGPT. We’ve seen a lot of LLM-as-an-assistant applications in the market for the past year, and I think that there’s an opportunity to apply the same perspective to the task of annotation.

Revealing ambiguity in our annotation guidelines

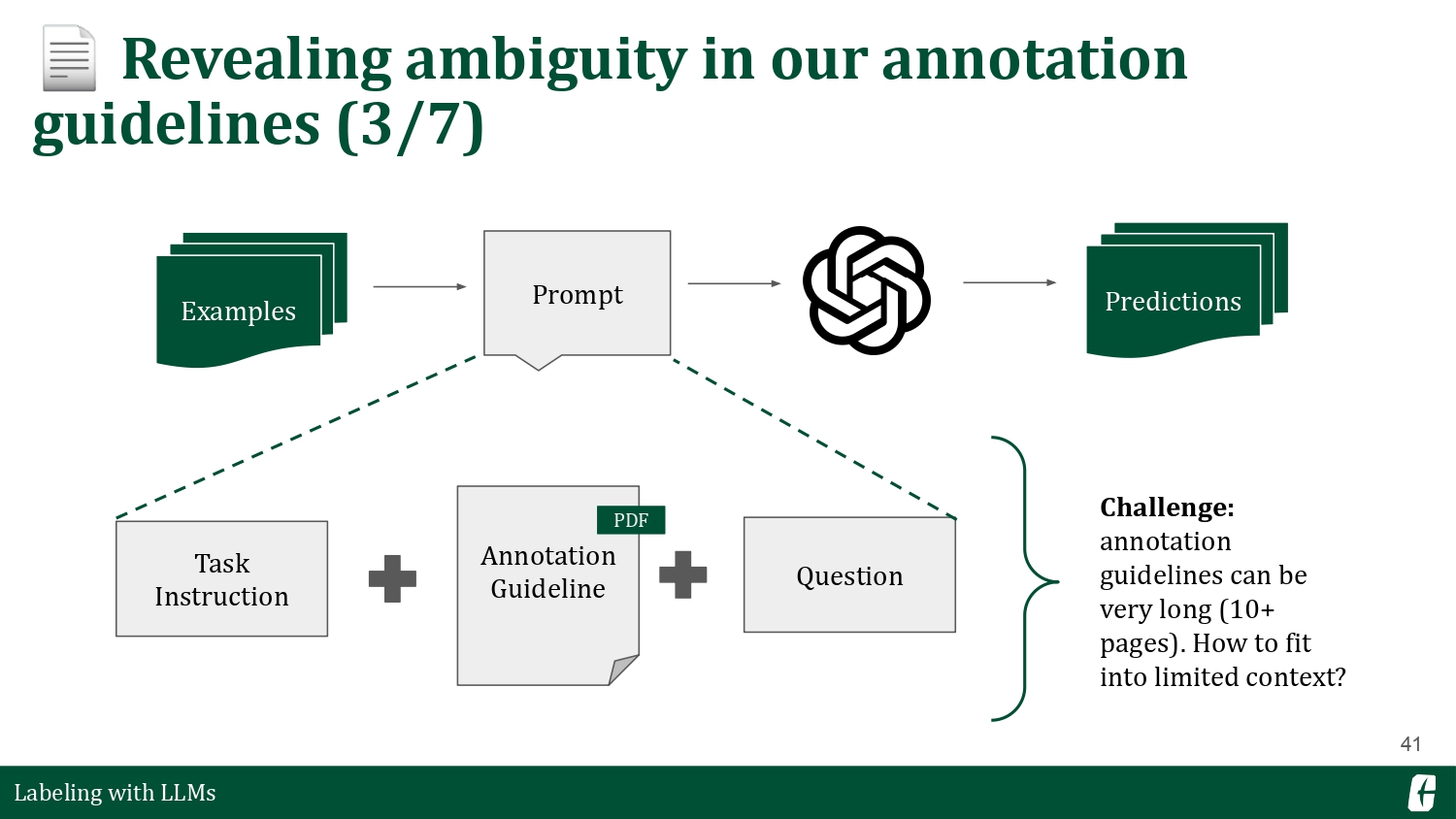

Finally, I’m curious how LLMs parse information originally intended for humans. In most annotation projects, researchers write an annotation guideline to set up the parameters of the labeling task. These guidelines aim to reduce uncertainty about the phenomenon we are annotating. We can even think of these as prompts for humans!

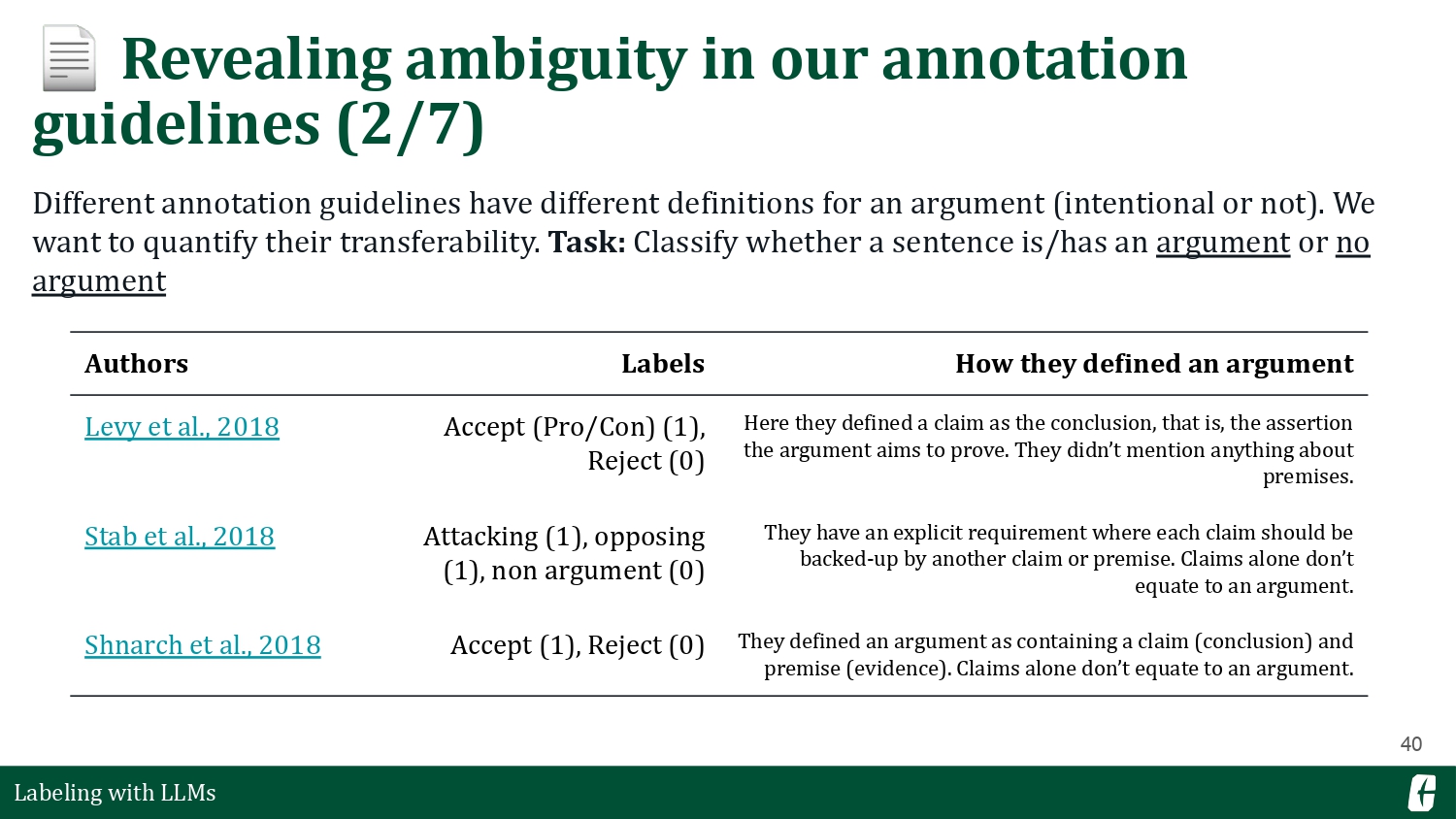

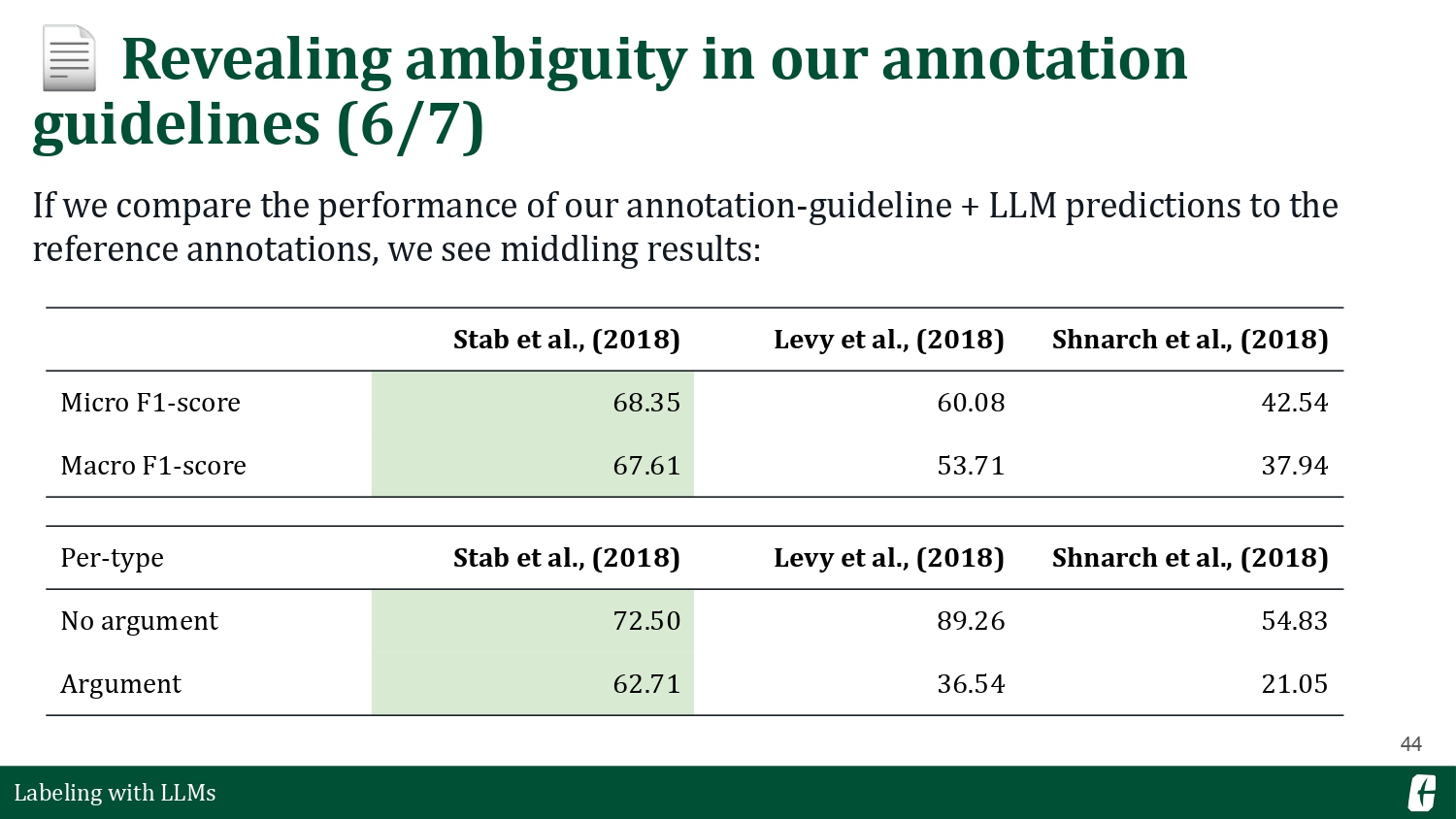

This time, I want to focus on a simple task: determine whether a statement is an argument. It sounds easy because it’s “just” a binary classification task. However, after looking through various argument mining papers and their annotation guidelines, I realized that they each have their definition of what makes an argument!

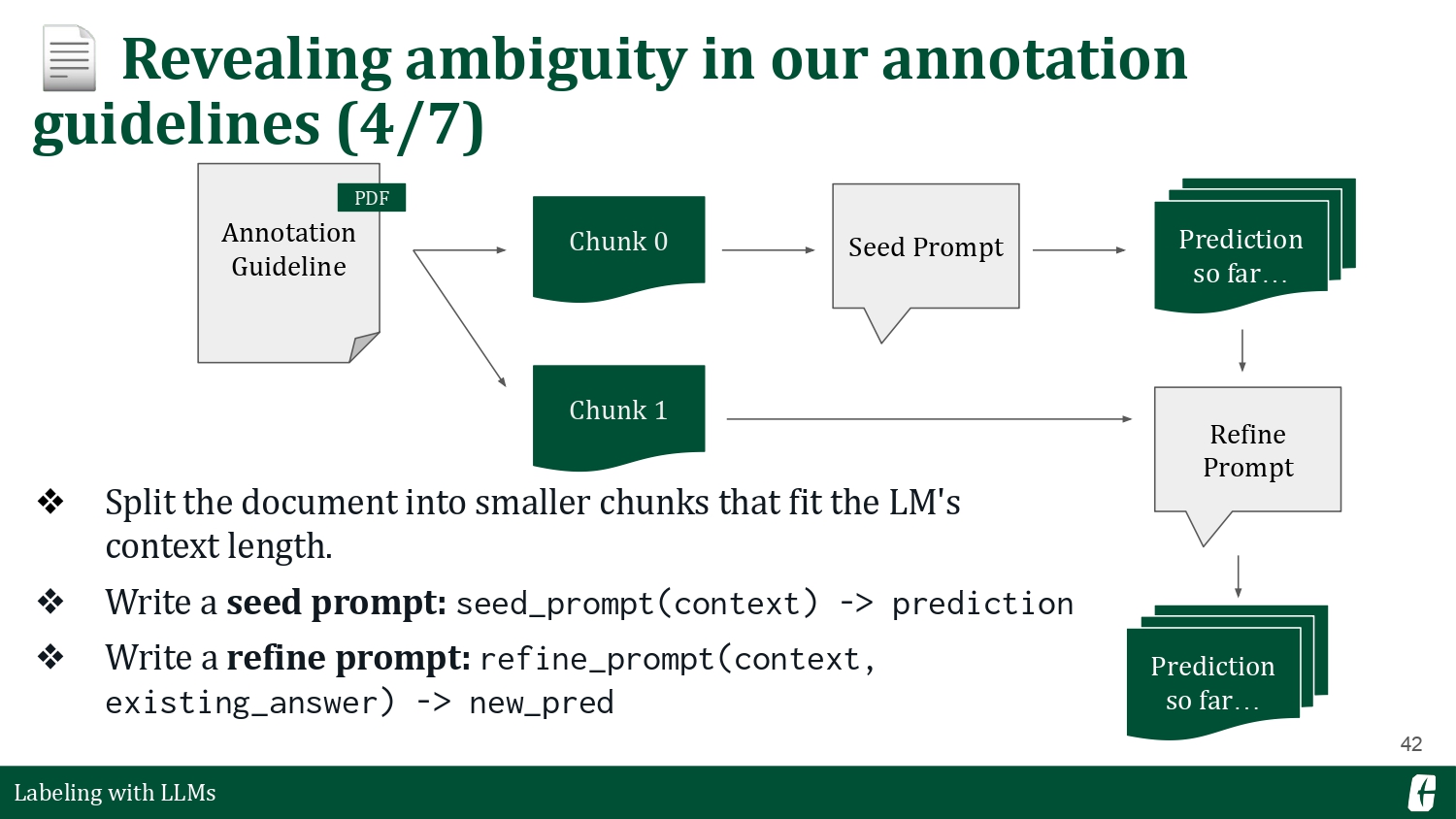

So, this got me thinking: what if we include the annotation guideline in the prompt? You can check my entire experiment in this blog post. Back then, you could not fit a whole document into an LLM’s limited context length, so I used a continuous prompting strategy that showed chunks of the document and let the LLM update their answer based on new information. Langchain calls this a “refine chain” in their docs. As an aside, I’ve opted into using minichain in my recent projects as it is more lightweight and enough for my needs.

Including an annotation guideline in the prompt resulted in worse results—surprising. I couldn’t delve further, but I hypothesize that writing prompts for LLMs have a particular “dialect” vastly different from how we talk as humans. Annotation guidelines were written with humans in mind, and perhaps some qualities don’t transfer properly into LLM prompts. There are many confounding factors, of course. Maybe the refine strategy is not the best, or maybe I should’ve processed the text much better. An LLM’s prompt sensitivity is still an open problem.

But I learned one thing: we can use LLMs as a “first pass” when iterating over our annotation guidelines. Typically, you’d start with a pilot annotation with a small group of annotators as you write the guidelines, but there’s an opportunity to incorporate LLMs into the mix.

Final thoughts

Before we end, I want to share an important question before you begin your annotation projects. You should always ask yourself: what is the label supposed to reflect? Knowing what you want to use the collected dataset for is paramount.

Rottger et al. (2022) named two paradigms for data annotation: prescriptive and descriptive. Prescriptive annotation is usually found in linguistic tasks such as named entity recognition or parts-of-speech tagging—where there is a “correct” answer for each instance. Here, you already have a function in mind and need to collect enough data to train a reliable model. On the other hand, descriptive annotation aims to capture the whole diversity of human judgment. You’d usually find this in subjective tasks like hate speech detection or human preference collection.

LLMs are pretty good at prescriptive annotation tasks. Some empirical evidence that supports it (Ashok et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2023), and it allows us to access the web-scale data it was pretrained upon.

And now to my final point: despite their web-scale and zero-shot capabilities, LLMs are only as good as how well you prompt them. During my early days in data science, there is this common adage: “garbage in, garbage out.” Usually, we say this when we want to refer to bad data. The problem with prompts is that the degree of freedom is much higher, which introduces ambiguity to our inputs. Hence, I don’t recommend using LLM outputs straight from the firehose and serving it immediately. There should be an intermediary step that minimizes this uncertainty, and that step is human annotation.