Thinking with pen and paper

Obsidian, Notion, Evernote, I’ve tried them all. With the deluge of note-taking and knowledge management apps everywhere, it feels nice to go back to my desk, pick up a sheet of paper, grab my pen, and start writing my thoughts down. There’s a serene feeling whenever I work with these analog tools, and it’s a delightful complement to my software job.

In this blog post, I’ll discuss why I enjoy working with my “analog tools for thought.”1 I’ll talk about it in three dimensions—simplicity, intentionality, and historicity. Note that this post isn’t a slight to digital apps and systems; I do use them, and they also embody the same qualities, just executed differently. I hope this entices you to start putting more intention when thinking with pen and paper.

Simpler interface

First, I’d like to differentiate between tools and systems. Tools are instruments to achieve something, and systems are the organization of such. The table below illustrates this concept.

| Tools | Systems | |

|---|---|---|

| Analog Interface | Notebooks, pen, paper, sticky notes | Bullet journaling, focus planners, Zettelkasten (slip-box) |

| Digital Interface | Obsidian, RoamResearch, Notion, Emacs org-mode, Notepad, Evernote | Zettelkasten (slip-box), productivity integrations, etc. |

You can use the same system even if the tool is digital or analog. Zettelkasten is a good example. It started as a physical slip-box (pen and paper) and is now widely used in most personal knowledge management (PKM) frameworks today. Systems can be intrinsically complicated, and I argue that using digital tools can compound this complexity.

Pen and paper is, well, pen and paper! There’s just a one-to-one correspondence between me and the tool. Sometimes, I find digital apps urging me to integrate with another application or extension: connect to calendar, install this, install that (and sure, it may also be my own damn fault). They force me to get into a “system” rather than focus on what the tool provides. It’s overwhelming. Over-optimization leads to empty work, giving me a feeling of productivity in the absence of output, like quicksand. It hampers me from doing actual work.

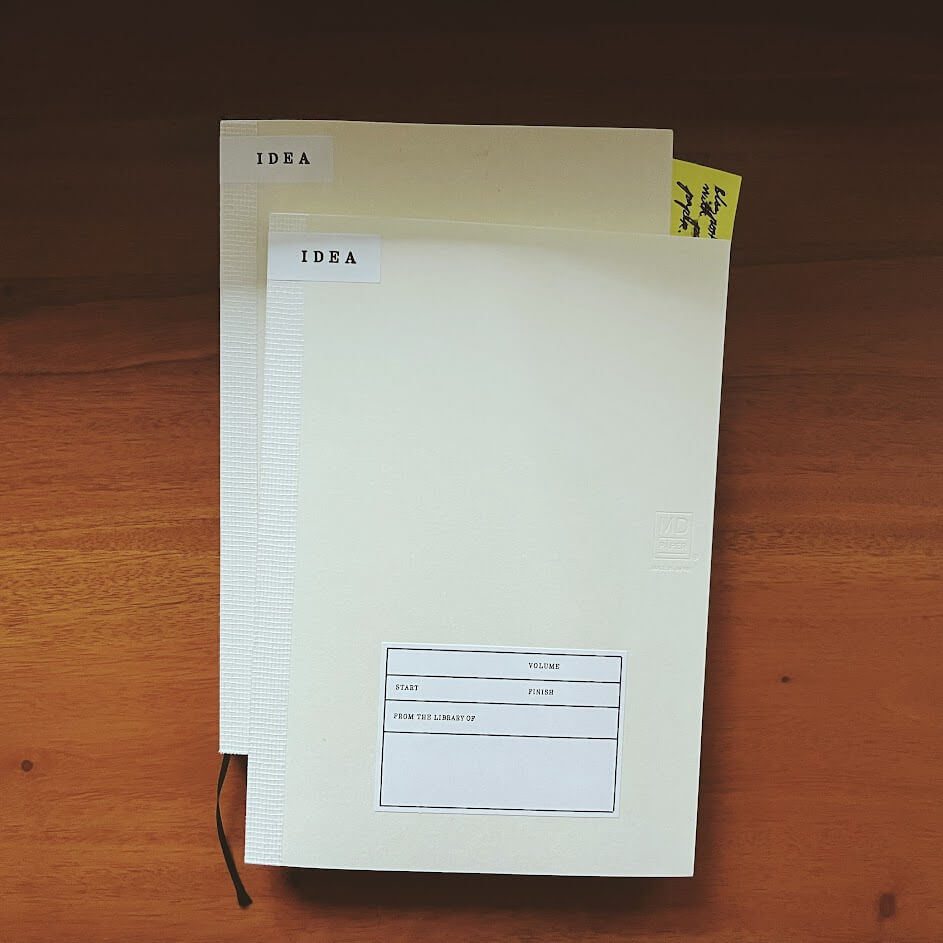

My work notebook (Midori Notebook A5).

The simplicity of pen and paper allows me to shape my system as I go along. Mine’s quite plain: an A5 notebook for work, a smaller notebook for journalling, and a pen. I like to think of thoughts as streaming information, so I don’t need to tag and categorize them as we do with batched data. Instead, using time as an index and sticky notes to mark slices of info solves most of my use cases.

Graph notebooks like Obsidian think of information as batched data. So you have a set of notes (samples) that you try to aggregate, categorize, and connect. Sure there’s a use case for that: I can’t imagine a company wiki presented as streaming info! But I don’t think it aids me in how I usually think. When thinking with pen and paper, I prefer managing streamed information first, then converting it into batched information later— a blog post, documentation, etc.

Sparks intentionality

I find writing a conscious effort. There’s physical exertion in each stroke: my muscles tense, my fingers guide the pen, and I feel the friction as it interacts with the paper. One thing that I appreciate when writing on paper is that I feel more present. It signals my brain that this activity is not just typing or writing, but thinking.

Sure, there are tradeoffs; sometimes, I think faster than I write, but I see this as a feature: it forces me to write down the salient aspects of my thinking. On the other hand, it’s pretty easy to fall into mindless writing when using a keyboard. It’s even easier to fall into the temptation of copy-pasting from the source material. The influx of information, coupled with the convenience of note-taking apps, makes it easier to collect rather than synthesize.

My notebooks for journalling since 2018 (Rhodia Webnotebooks).

Perhaps this is why Zettelkasten worked well during the time of physical slip-boxes. Information was not cheap. You have to physically go to a library, borrow some books, highlight important passages, and return them at the end of the day. Sure, you can copy paragraphs word per word, but the physical exertion of writing can tire you down. So instead, you’ll paraphrase or synthesize that information. It becomes a necessity than a guideline. When thinking with pen and paper, I feel intentional.

Analog tools also allow me to express my intention freely. For example, when using a blank notebook, I can write anywhere: begin from the bottom, on the margins, or intersperse it with quick diagrams or illustrations. On the other hand, note-taking apps usually force me to think line by line. It’s not bad, but it misses out on several affordances that pen and paper provides.

I like writing on blank paper (pen and ink: Lamy 2000 and Aurora Black).

Provides history

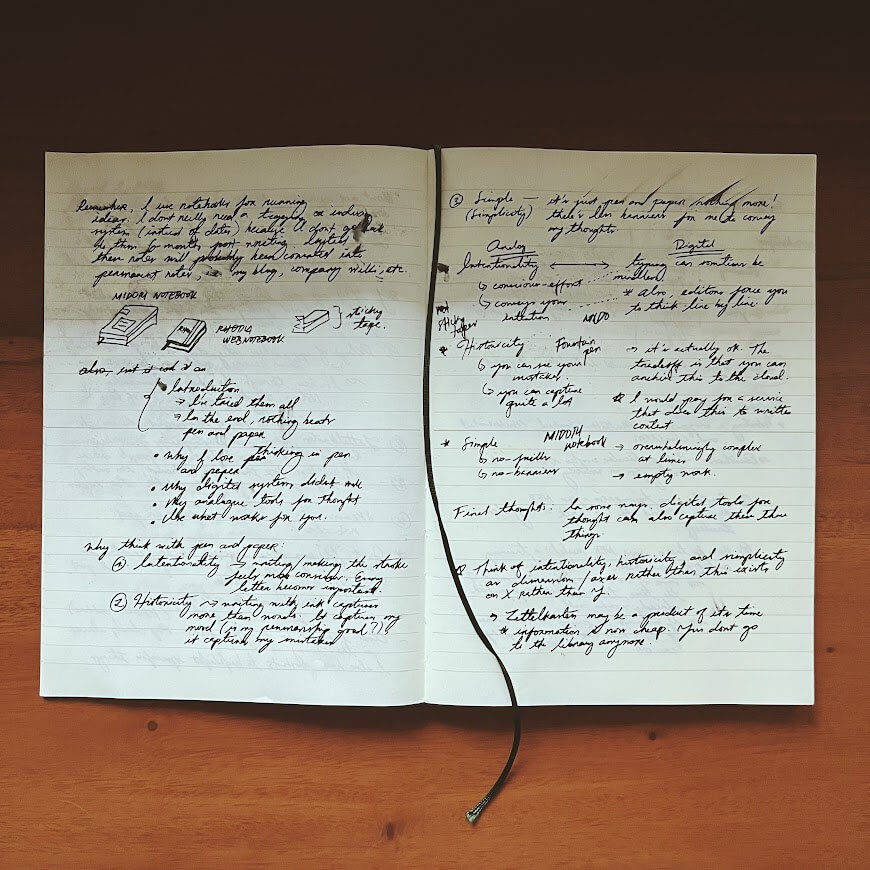

Writing with ink captures more than words. It captures my mood and my mistakes. I remember in my college chemistry classes, we were instructed never to tear off or hide any error we made in our lab notebooks. Instead, we should mark it with a strikethrough. I brought this practice up to this day, and it’s nice to see the small corrections, marginalia, and scribbles representing the unrefined parts of my thought process.

I’m the only one who can read my penmanship.

It’s fun to go back to my old notes and say: “Oh, I was a little bit stressed when I wrote this down.” There’s an archival element in it that digital formats cannot capture. Sure, it’s a bit of a reach to say that my written notes are better for preserving my thoughts—if they got lost or burned down, then it’s all gone. What I’m talking about here is the written note’s capacity to encapsulate “what really happened” during the time I thought about a particular idea. In a text editor, everything is reduced to the same font, sterilizing those details away.

I’ll gladly pay for an application or service with the affordances of writing in pen and paper while allowing me to back my notes up in the cloud. However, I agree that lifetime archival is a tradeoff I have to pay.2 Lately, I’ve been using a fountain pen with archival ink. This type of ink is waterproof and ensures that my writing won’t fade over time. Sometimes, I just don’t let this stress me out, and I opt for the inks I love and enjoy. My notes contain streaming information, after all.

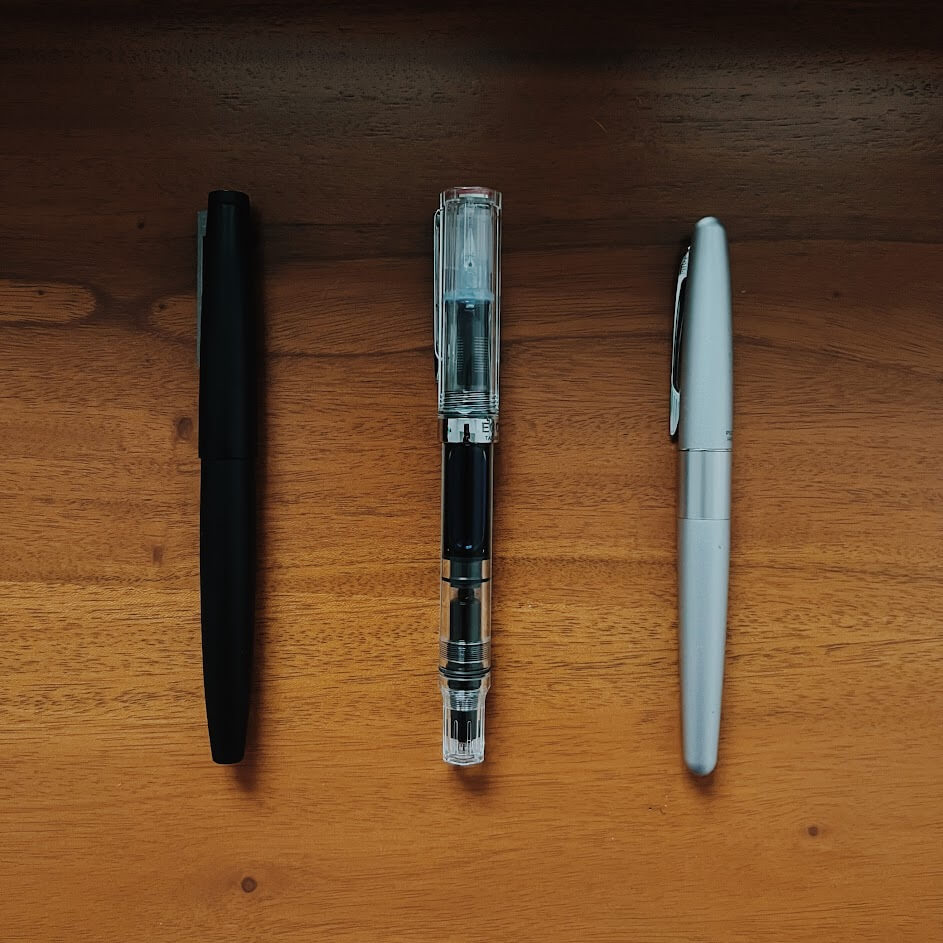

My pens through the years (from left to right: Lamy 2000, TWSBI ECO, Pilot Metropolitan).

Final thoughts

I wrote this blog post as a love letter to my analog writing instruments. They’re almost invisible; they’re just there, helping me in my knowledge work. Because of that, I may have spoken strongly against other digital systems–don’t raise your pitchforks; I use them too! Nowadays I use Obsidian and Zotero; the latter a by-product of my grad school days. However, I try to go against the common PKM practices and I use them to bookmark information.

But in the end, the best thinking system is the one that works for you. I can’t really say if I’ve been more productive with pen and paper, I just find it more frictionless and delightful, and that’s enough. I also mentioned Zettelkasten many times in this post, but I don’t do that anymore—I just did a 1-month dry run and it felt tiring. Pen and paper just gives me the bare essentials. I can get straight to work and not worry if something is a literature note or a permanent note.

As an engineer, I love making things complicated (winks). You’ll notice that I’m using fountain pens with this ink, and a notebook with that paper-grade. But the good thing about pen and paper is that these instruments are not necessary. I do it because it’s fun! And you don’t have to (although trust me, fountain pens changed my writing experience).

In the world of productivity porn, it sounds edgy to say “I use pen and paper.” I mean, it’s just pen and paper! But if we’re optimizing for feelings3, I’ll say that I find the most delight when thinking with pen and paper. I hope you do too!

Changelog

- 08-06-2022: See the discussion on Hacker News

Footnotes

-

I mention this with a tone of seriousness mixed with playful banter (tOoLs fOr tHoUgHt). I think the “tools for thought” space is essential; I believe in tools that help augment how we think and process information. However, I noticed that in recent years, we’ve been over-optimizing this process where tools became increasingly overwhelming to even facilitate knowledge work. ↩

-

And it’s not that bad anymore! Whenever I take photos of my notes with my phone, it reliably detects the text (even with my penmanship) and saves them to the cloud. ↩

-

I stole the title from this Substack post. I cannot put this much better than them: “we’ve chosen to optimize for feelings— to bring the quirks and edges of life back into software. To create something with soul.” Enjoyment is an important component of my day to day. ↩